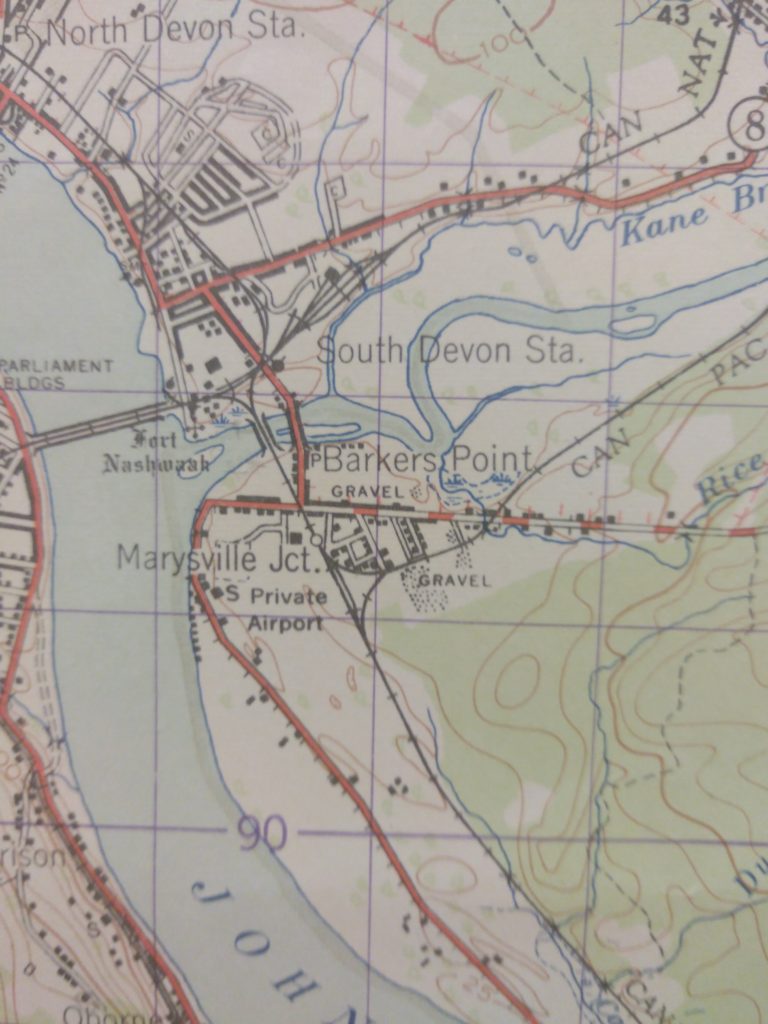

I worked in Fredericton, New Brunswick, for a year and a half as an archaeologist with the province. After much consideration, I decided to leave my job, and return to St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. It was not an easy choice, but an important one for my physical and mental health. While in Fredericton, I did not have much time to do any aviation research into the area, or much research at all for that matter, but did happen upon a little aviation history while writing a report on the area of Barkers (or Barker’s) Point, a community that has amalgamated into the greater Fredericton area. Unfortunately, there are holes in this research as I could not get to the provincial archive before I left, so am relying on what little I found in a couple of books about the Fredericton area in the Fredericton and Oromocto libraries and the internet.

Saint John and Moncton had airports in the 1930s, but Fredericton only had aviation use as being on a List of Airharbours Available for Use. A site in Embleton, west of the city, was considered between 1930 and 1932, as was an area in Nashwaaksis for a British Commonwealth Air Training Plan aerodome in 1936, and the R.H. Carten property on Maryland Hill, but neither project happened, mostly due to the anticipated costs.

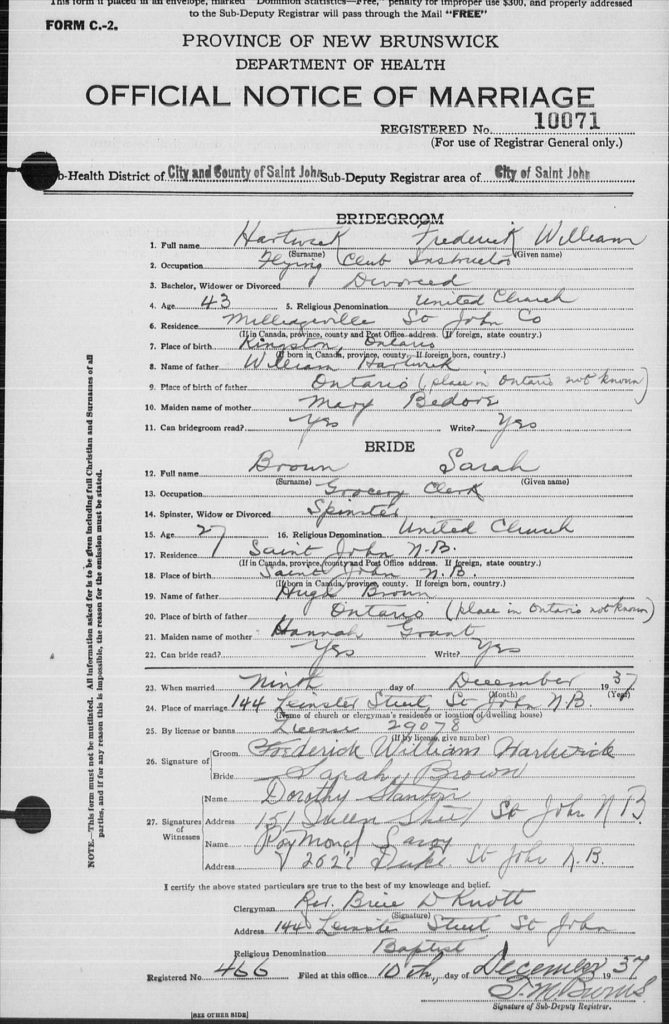

The airfield was built in 1941 with the efforts of Frederick William Hartwick, and the small airfield was established for light aircraft and daytime use. The Hardwicks purchased a farmer’s field and some surrounding properties in Barkers Point, a community mostly known for farming and logging. Harwick was a pilot who worked in Saint John where he flew mail between there and Fredericton during the 1920s and 1930s. He did attempt to establish a mail and passenger route to his airfield, but the site was determined to not be suitable.

Like many pilots of the time, he was also a flight instructor, an aircraft maintenance engineer, and could rebuild engines and airframes. In his move to Fredericton, he brought with him two DeHavilland Gypsy Moths and a Piper J-3 Cup. Once established, Hartwick, with his wife, Sarah, and his son from a previous marriage, Percy, lived in a farmhouse on the airfield property and used a hay barn as an airport hangar. During the winter, the Hartwicks would move to North Devon, and would offer flights off the frozen Saint John River for $2 a flight.

With the presence of the airfield, Paul Horncastle and Fred Butland, students at the Fredericton High School, organized a number of their fellow students to establish an air cadet squadron in the area. In January 1943, #333 was launched, and the students spent time at the Barkers Point Airfield under the instruction of Hartwick and working with the airfields Hawker Hurricane. In the summer, the Barker’s Point Flying Club was started, but its activity was limited due to wartime fuel restrictions.

In 1944, several Lysanders few over Fredericton. One had engine issues, and used the Barker’s Point Airfield as an emergency landing. The soft, packed gravel and long grass airstrip caused the aircraft to roll and flip over. I tried to find more information about this incident, but without luck. The aircraft was dismantled and removed by the Air Force (I assume in this case the RCAF, but also could not find one that had been struck off or sent for repair after an incident in Fredericton). Jones and Jones 2007 also state there is a photograph of the incident, but it is not included in the book. Any further information would be appreciated.

Hartwick leased the airfield to James Sturgeon in 1945, who also purchased Hartwick’s three aircraft. Adding to his aviation business, Sturgeon had the dealership for the Fleet Canuck, the Seabee, and the Stinson planes. He used seven Fleet Canuck aircraft, including what was supposedly the first to come off the assembly line, as part of a training school. New hangars were added to Barkers Point, and his dealership sold aircraft throughout Quebec and the Maritimes. In 1946, Hartwick’s licence was transferred to Sturgeon. In that same year, Sturgeon offered chartered flights, demonstrations, and training for pilots and engineers. The airfield became a year-round operation, with three jeeps used to keep the runway clear in the winter.

In 1947, on January 24, a fire broke out in the main hanger. This destroyed three Fleet Canucks and two Cirrus Moths as well as four motors, some tools, and all of the office flying records. In the worst of luck, the fire destroyed the telephone line, making it impossible to call the fire department.

The University of New Brunswick Flying Club had a hangar at the airfield which they rented from Sturgeon. Most of the staff were former RCAF pilots who worked as instructors. The first official UNB flight took place on 29 January 1947. Luckily, their hangars were not touched by the fire a few days previous. The first flight was flown by Flight Club president and former RCAF bomber pilot, Thomas Prescott, and UNB President Milton F. Gregg. Faculty and students were present to witness the event. With the Flying Club, UNB became the first Canadian university to have its own aircraft.

In the spring of the year, Sturgeon’s part of the Barkers Point Airfield had recovered from the fire and had added Maritime Central Airways Limited, a mail and passenger service between Fredericton and the rest of Canada. Maritime Central Airways scheduled operations with the Lockheed 10 using Barkers Point in the fall of 1948.

In April 1949, Barkers Point Airfield was taken over by Gaetano Digiacinto, but he allowed the airfield licence to expire in the following year and never returned it. The airfield was left to become farmland. In 1947, the site for the current Fredericton Airport, in Lincoln, was chosen. In fact, Sturgeon was asked to assist with the surveying for the new airfield. Other potential airport sites were investigated in the 1940s, including a 1943 survey near Rusagonis and a 1945 survey in Lincoln. The land for the Lincoln site was expropriated in 1948 and work began that same year.

Sources

Jones, T. and A. Jones

2007 Historic Fredericton North. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing Ltd.

Provincial Archives of New Brunswick.

2019. Vital Statistics from Government Records. Accessed 05 September 2019.

YFC

2019. History of the Airport. Aeroport international de Fredericton International Airport. Accessed 05 September 2019.

There is a facebook post with some interesting, but uncited, photos here. While they look to be from the New Brunswick Barkers Point, there was also an airfield in Toronto with a similar name.