First published on August 2, 2013, this is a site that I have not yet been able to return to. I won’t get into the details as to why, but some reasons have been due to health. I do have a few more documents than when this was first published, so I do plan to update the information a little and share a better analysis. I do still hope to return to the site, or if nothing else, visit the memorial at the top of Crash Hill. There are still many people in Newfoundland who remember this incident, and some who were directly involved who have stories to share. I do not have notes or recordings of these stories, but I hope they do get shared publicly as it is another important part of our aviation history.

———

Adapted from Daly and Green 2013.

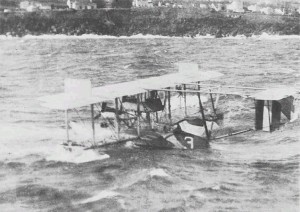

On 3 October 1946, an American Overseas Airlines (AOA) NC90904, a DC-4, took off from Harmon Airfield in Stephenville, NL at 0833 GMT. Moments later it crashed in to Hare Hill, killing all 8 crew and 31 civilians (Wilkins 1946). This was “the worst disaster in the history of American commercial aviation” (Canadian Press 1946) with a larger death toll than the Sabena disaster which took place in Gander, NL, two week previous. The aircraft had departed from LaGuardia, New York, destined for Berlin, Germany, with stops scheduled in Gander, NL, and Shannon, Ireland (Author Unknown 1946b). The AOA aircraft had been diverted to Stephenville due to thick fog around Gander (Canadian Press 1946). The passengers consisted of 12 women and 6 children en route to be reunited with family stationed in Europe as well as businessmen bound to assist in the rebuilding of Berlin (Wilkins 1946).

Stephenville had strong ties to the United States Air Force, as seen by the monuments found throughout the town. Photo by Shannon K. Green 2012.

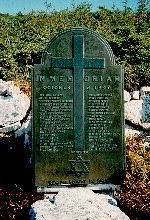

The DC-4 was scheduled to leave from runway 30, but a sudden wind change diverted the aircraft to runway 7. The aircraft impacted the side of Hare Hill about 2 and a half minutes after take-off (Wilkins 1946). The subsequent explosion could be seen from the airport (Landis et al. 1947). At first light, the site was checked for survivors by passing aircraft, but none could be found (Author Unknown 1946a). A recovery mission departed at first light that morning to investigate the incident and cover the wreckage. Initially, the plan was to blast above the site to cover the wreckage and human remains, but when the size of the site was established, it was decided to create a mass grave near the wreck site for the human remains (pers. comm. Leo Fitzgerald 2013). Over the next couple of days, bodies and personal effects were recovered, and where possible, identified. The rocks above the site were then dynamited to cover the aircraft, but the site was too large to be completely obscured (Fagan & Fitzpatrick 1946). Personal reports from Nelson Sherren (2011) indicate that the hill may have been blasted again in the 1970s in an attempt to cover more of the aircraft. In 1946, only days after the crash, a memorial cemetery was built at the summit and a large monument which lists the names of the victims was air lifted to the memorial cemetery. Family members were invited to view the site and drop wreathes from an aircraft passing overhead. A Catholic, Protestant and Jewish burial service was held on the helicopter for those who had perished (Time 1946). In 1989, the memorial cemetery was redone when Dixie Knauss, a surviving family member, visited the cemetery and found that all of the crosses had fallen. She attempted to secure acrylic crosses, such as are used in United States military cemeteries, but could not and the site was redone with wooden crosses (Knauss 1989).

More of Stephenville’s aviation history as seen by a repair hangar and a Cold War scramble station. Photos by Shannon K. Green 2012

Over time the site was lost. The hill was now known as Crash Hill, and it was common knowledge in Stephenville that a plane crash had taken place, but the location and specifics about the crash were less known. In fact, hunters and hikers had been exploring the area trying to find the site, but could not (pers. comm. Don Cormier 2012). It was believed that when the site was dynamited it had been successfully obscured and researchers were unsure that anything would remain.

Alder Pond. Crash Hill is visible in the distance. Photo by author 2012.

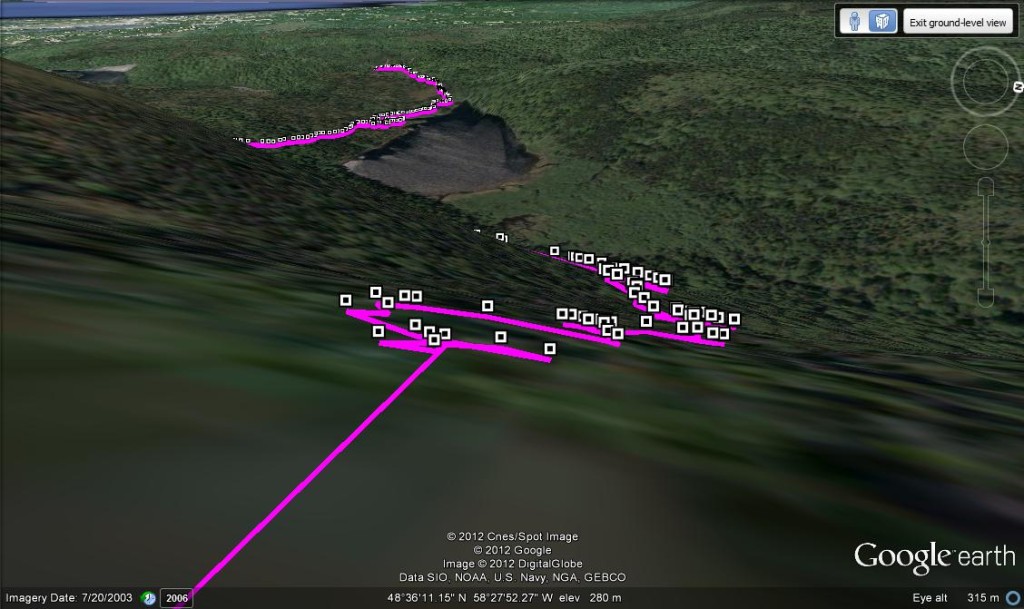

In 2012, a small group of researchers, lead by guide Don Cormier, and based on a picture found in Our Lady of Mercy Church on the Port-au-Port in comparison to GoogleEarth images, located the site. Unlike what was expected, most of the wreckage remains. Much is obscured by blasted rock, which also makes the site extremely treacherous, but the aircraft remains. Archaeologists did a preliminary survey of the site, taking GPS readings and photographing pieces, but it was obvious that the site was too large to fully survey in the little time the team had on site. On a second trip that year, videographer Dave Hebbard and Cormier returned to the site and found further wreckage that was not photographed nor mapped on the first trip.

Route taken from Little Long Pond to the crash site.

View of the route from the highest data point.

Our Lady of Mercy church and museum in Port-au-Port. Photo by Shannon K. Green 2013.

Next week, a slightly larger team will return to the site for a two to three day stay in an attempt to properly survey the site, find the extent of the site boundaries, and survey the memorial cemetery at the top of the hill. The site is difficult to access as Crash Hill is a fairly isolated site and the incline of the hill seems to be around 60 or 70 degrees. That coupled with the loose rock leftover from blasting makes it a difficult site to navigate and impossible to bring out much in the way of archaeological equipment. Researchers will be limited to a handheld GPS and measuring tapes and a compass to survey the site.

In an attempt to illustrate the slope of the hill, the top picture is of the author coming down from the crash site, and the bottom is of Shannon Green climbing up the hill toward the crash. It is a difficult hike.

Once this survey is complete, the data will be mapped to give a better idea of site distribution. As well, when the top of the hill is mapped, it will show the extent of the damage that time and the elements has done to the memorial cemetery, which will hopefully end in the site being redone, perhaps with the plastic military crosses that Dixie Knauss wanted in 1989 (Knass 1989).

The museum entrance is around the back of the legion. It’s a great museum, well worth the visit. Photo by author 2013.

*03 October 2013 update: Myself and my team did not make it out to the site this year, we were kept away due to poor weather. I hope to get out next spring or early summer to continue to work. The presentation at the Stephenville Regional Museum of Art and History was well attended, and I had the opportunity to meet many wonderful people from the area, many of whom were happy to share stories with me. I hope to have many more conversations with the people of the area, and do much more research that will be of interest to them.

*04 April 2016 update: Poor health has kept me away from the site. It is a difficult hike and while the research is important, I must put my own well-being first. I have gotten much stronger since my health scare in 2013-2014 have hope to soon be able to push myself into more strenuous hikes.

References Cited

Author Unknown

1946a Fears Expressed All of 39 Occupants Perish in Crash; Plane Bursts Into Flames. Evening Telegram, 03 October 1946.

Author Unknown

1946b Fire on the Hill. Time Magazine, 14 October 1946.

Canadian Press

1946 Twelve Women and Six Children Are Among the Victims. Daily News, 04 October 1946.

Daly, Lisa M. and Shannon K. Green

2013 Crash Hill: A Survey of the 1946 AOA Crash in Stephenville, NL. On file at the Provincial Archaeology Office, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Fagan, J. and G. Fitzpatrick

1946 Report on Wreck of American Overseas Airlines Airliner on Mountain Eight Miles North East of Stephenville. Report to the Chief Newfoundland Ranger, GN 13/1/B Box 355 File 3.

Knauss, Dixie L.

1989 Personal communication from D. Knauss to Francis Walsh, 18 April 1989. On file PANL GN 4/5 AG 57/7 Box 2 Aviation.

Landiss, J.M, Oswald Ryan, Josh Lee and Clarence M. Young

1947 Civil Aeronautics Board Accident Investigation Report American Overseas Airlines, Inc. Stephenville, Newfoundland, October 3, 1946. On file PANL GN 4/5 AG 57/7 Box 2 Aviation.

Wilkins, F.S.

1946 Accident to American Overseas Airways Aircraft NC 90904 at Stephenville 3rd October 1946. Royal Canadian Air Force Accident Investigation Report Newfoundland Government No. 2. On file PANL GN 51/21.