Figure 1. Archaeologists Dr. Mike Deal and Dominique Kane examining the wreckage. Photo by author, 2010.

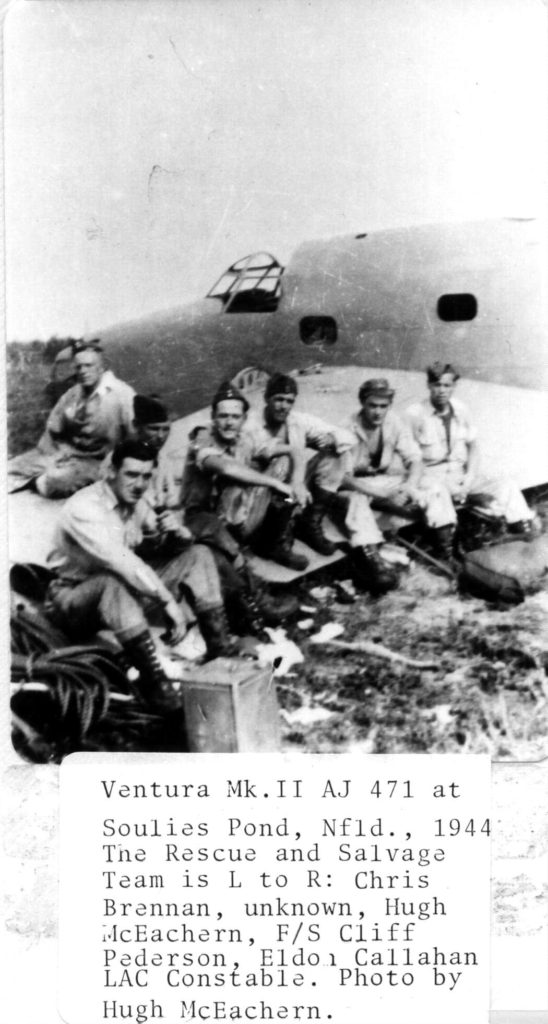

Royal Air Force Ferry Command Ventura AJ471 (AfAo-01) crashed in a bog between Benton and Gander, near Soulis Pond, on 18 November 1942 with no fatalities (fig. 1). As it is an RAF crash, there is very little official information available, and this is one that is not mentioned specifically in Christie’s Ocean Bridge (usually the best source of Ferry Command information). The Ventura Memorial Flight Association (VMFA) did some research a few years ago on this crash, and managed to interview Hugh McEachern about the recovery. The recording has since been misplaced, but I did receive some information from notes about that interview that were found. According to Anthony Jarvis of VMFA (2011), McEachern indicated that the crew recovered parts from the aircraft by transporting them over nearby rivers to the railway (I imagine this means brought to Soulis Pond to meet the railway in Benton). The propellers were brought out on the backs of the recovery crew, and McEachern said they had to wear their hats sideways to carry them! He also remembered a Mickey Mouse Cocktail cartoon on the aircraft, a possibility because Venturas were built in a factory next to the Disney Burbank studio and cartoonists would often paint motivational cartoons on the aircraft (fig. 2), but no evidence of such a cartoon remains on the site. That said, the nose of the aircraft is missing. The rescue and salvage team assigned to the site consisted of Chris Brennan, Hugh McEachern, Cliff Pederson, and Eldon Callahan (fig. 3).

Figure 2. Disney art on display at the Alberta Aviation Museum. Photo by author, 2015.

Figure 3. The rescue and salvage crew. From the VMFA collection.

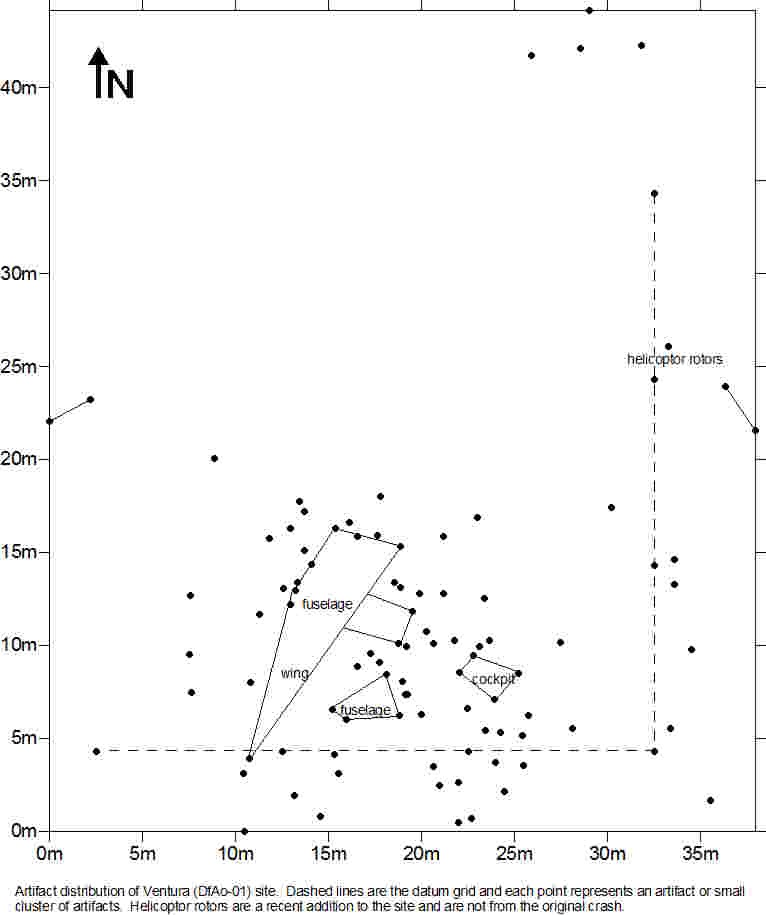

This Ventura is located in an open and relatively dry bog which made the site easy to survey. Not only was this site surveyed with a surveyor’s level, but it was also swept with a Fisher Labs CZ-21 Deep Search Land and Underwater Target I.D. Metal-Detector. Once the metal detector was calibrated it was passed over the majority of the site (the pieces that were over 30m from the main wreckage were not included in this sweep) and each hit was marked with a peg. These areas were then dug up until the metal item was uncovered and removed from the bog. Measurements and pictures were taken, then the items were replaced and reburied. Of the 91 measurements taken on the site, 25 were metal detector finds. Most of the wreckage is concentrated around the fuselage, except for the helicopter rotors, four pieces located beyond the rotors, and a large piece of fuselage that was cut away using an axe and dragged away (map 1 and 2).

Map 1: Site distribution. Does not include the large cut piece of fuselage.

Map 2: The Ventura as seen from GoogleEarth. Note the main wreckage (red circle) and the cut piece of fuselage (blue circle). GoogleEarth 2016.

The site is in good condition, but evidence indicates it has also been heavily disturbed. The aircraft is located on an unofficial snowmobile trail, as evidenced by the extensive graffiti inside the aircraft, mostly dating to the winter months (fig. 4). Based on site visitor accounts and images, pieces have been removed and moved around the site, such as the cockpit and a large section of fuselage which has been removed using an axe and moved to the edge of the bog (fig. 5). It looks as if this section was dragged from the site until it became tangled in the small trees and alders that are on the edge of the bog.

Figure 4: Graffiti scratched into the paint of the Ventura. Photo by author, 2010.

Figure 5. Section of aircraft that has been cut and dragged away from the main site. Photo by author, 2010.

This damage is reactively recent (within the past 30 years) as indicated by aerial images taken by Bill Parrott in 1974 (fig. 6). This image indicates that the aircraft was relatively intact (the starboard wing was detached), and since then the tail was removed (still on the site) and large sections of the fuselage were removed. Some of it is still relatively close to the site, but too large to easily move back. A 2003 image of the War Bird Registry website taken by VMFA indicates that in 2003 the aircraft has already been cut up, but it does not look as if anything further has been removed from the site (fig. 7). The cockpit and tail assembly seem to move about the site, but generally stay close to the aircraft (Hillier 2010). In the 2010 visit, the cockpit was moved to the side of the aircraft and the tail to the opposite site (fig. 8). Also, smaller pieces look to have been removed and moved from the main area of the crash. The site is also littered with pop tins and cigarette packages, giving not just a timeline of Pepsi logos, but further indicating long-term site sure. Some of the last of disturbance can be attribute to the fact that the site is generally visited in the winter when much of the smaller material will be buried under snow.

Figure 6: Aerial photo of the RAF Ventura taken in 1974 by Bill Parrott. Note how little damage has been done to the aircraft. On file VMFA.

Figure 7: Image of the Ventura taken in 2003. On file VMFA.

Figure 8: The Ventura site in 2010. Note the cockpit was still on site, but is hidden behind the fuselage in this image. Photo by Dr. M. Deal 2010.

Graffiti and secondary site use

The Ventura site is of particular interest because of some of the things left on the site. The first indicator that the site was on a snowmobile trail comes from the graffiti. While I do not understand the need to record ones name on an aircraft, it seems to be pretty commonplace (as seen at Burgoyne’s Cove and at the Digby site). Graffiti damages the aircraft, especially when it is scratched into the paint. Someone did leave a Sharpie in the aircraft, and that seemed to be doing far less damage to the aircraft (fig. 9). The graffiti that was dated was dated to the snowier months in Gander, which was a strong indicator that it was on a snowmobile trail. An informant from the area confirmed this.

Figure 9: Sharpie left on site and subsequent graffiti. Photo by author 2010.

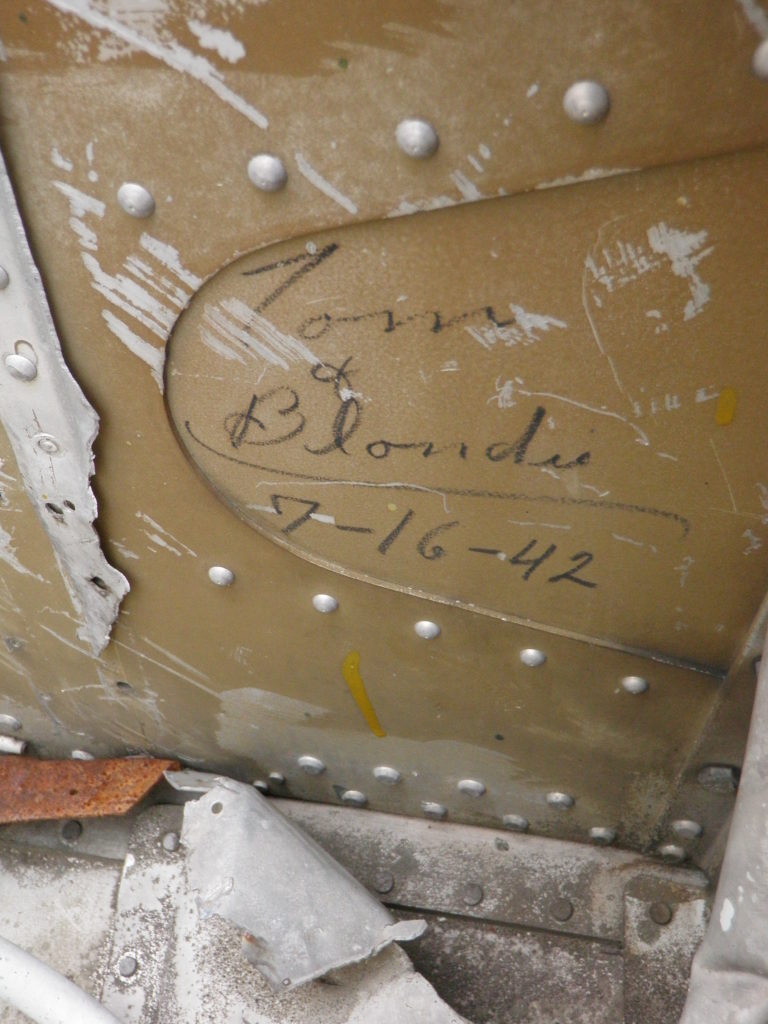

While I say that graffiti damages the site, at the same time it can be of interest. Inside the wing of the aircraft is graffiti from the factory. On 16 July 1942, during the construction of the aircraft, either Tom or Blondie wrote about their love (fig. 10). As of 2010, this pencil declaration was still clearly visible on the aircraft. How do you distinguish what graffiti is damaging and what is history is something that I cannot answer. In either case, it does give information about the aircraft and the site. Similarly, damage to a site, such as removing items for scrap, adds to the story of the site, but damages it and can destroy information and destroy the site for future visitation or research.

Figure 10: From inside the wing. Photo by author 2010.

Not only is the site used by local snowmobilers, but it is also used by 9 Wing Gander for run drills. Helicopter rotors have been placed on the site and Search and Rescue (SAR) will practice dropping people at the site and picking up the rotors (fig. 11). This is not uncommon for crash sites. They are often known to local SAR and make for suitable practice sites. There is a B-36 in Goose Bay which is used in a similar fashion. Typically, when these sites are used by SAR, they are treated with respect and whether people died at the site or not, are treated as memorials to those who served before them (9 Wing Gander 2008).

Figure 11: Helicopter rotors on site. Used for SAR training. Photo by author 2010.

Future of the site

Part of the reason why this site was included in my thesis was because of its potential for restoration. While the aircraft still remains on site, there is a local group, including aviation engineers and historians, who are looking to recover the aircraft to one day restore it and keep it in Newfoundland. This would of course be done with permission from the Provincial Archaeology Office as it is an archaeological site.

Figure 12: Another view of the Ventura. Photo by author 2010.

Sources:

9 Wing Gander

2010 Conversations with various personnel

Daly, L.

2015 Aviation Archaeology of World War II Gander: An Examination of Military and Civilian Life at the Newfoundland Airport. Doctoral (PhD) thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Hillier, D. (historian)

2010 Personal Communication

Jarvis, A. (Ventura Memorial Flight Association)

2011 Personal Communication