Last month I had the pleasure of presenting with a number of other wonderful people in a symposium about archives and flight. It was an interesting day, and I am very much looking forward to the new exhibit that will be opening at Admiralty House this spring about the 1919 Great Atlantic Air Race. I thought I’d share my presentation. The idea was to create an introduction to researching Second World War aviation sites in Newfoundland and Labrador, particularly Gander. This is a good starting place for anyone looking to start some research.

There are a few typos in the presentation; I wrote much of it while on the plane from Halifax to St. John’s, trying to hide the pictures of plane crashes in case anyone happened to glance at my computer.

My introduction to aviation archaeology was in 2007 when Dr. Deal was looking for archaeologists to work for him. We worked on the site of the crashed United States Army Air Force B-24M bomber, number 44-42169. This aircraft crashed on the 14th of February, 1945, during a winter storm, killing all 10 men on board. The research for this site was conducted primarily by Mike Deal and Darrell Hillier, so I just had to show up and do the archaeology side of things. For a great read about the history of people involved in this crash, and their families, check out Darrell’s MA thesis “Stars, Stripes, and Sacrifice: A Wartime Familial Experience of Hope, Loss, and Grief, and the Journey Home of an American Bomber Crew” available through MUN. To explain, aviation archaeology looks at the physical remains of aircraft and the infrastructure associated with aircraft. By definition, this could go back to the late 1700s with the lighter than air machines that were flying around continental Europe, but it tends to focus more on the modern period of heavier than air flight, such as that made by the Write Brothers in 1903. For the purpose of my own research, I have looked at the history of aviation around Newfoundland and Labrador from the interim war years and later. Aviation archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador was the recovery of a USAAF B-24 bomber submerged in Dyke Lake near Labrador City by Underwater Admiralty Sciences in 2004 with the archaeological assistance of Roy Skanes. Since then, Dr. Deal and Darrel Hillier have done much to list and record potential crash sites that are of historical significance, or are at risk.

To explain, aviation archaeology looks at the physical remains of aircraft and the infrastructure associated with aircraft. By definition, this could go back to the late 1700s with the lighter than air machines that were flying around continental Europe, but it tends to focus more on the modern period of heavier than air flight, such as that made by the Write Brothers in 1903. For the purpose of my own research, I have looked at the history of aviation around Newfoundland and Labrador from the interim war years and later. Aviation archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador was the recovery of a USAAF B-24 bomber submerged in Dyke Lake near Labrador City by Underwater Admiralty Sciences in 2004 with the archaeological assistance of Roy Skanes. Since then, Dr. Deal and Darrel Hillier have done much to list and record potential crash sites that are of historical significance, or are at risk.  Much of my research especially that around Gander, also falls under the heading of conflict archaeology, which is the archaeological study of human conflict. Gander is a special case in conflict archaeology, in that it is an area of non-combat, but with higher risks than are often associated with being located far from the fighting front. My thesis looked at 10 crash sites around Gander, recorded them, and researched each one to try to find the purpose of the flight, the crew on board (both those who survived and didn’t), what happened to cause the crash and if the archaeological record to tell us more, and what has happened to the aircraft since, and what is the condition of the crash site. I also conducted an excavation of the Globe Theatre on the Canadian side of the Gander airbase.

Much of my research especially that around Gander, also falls under the heading of conflict archaeology, which is the archaeological study of human conflict. Gander is a special case in conflict archaeology, in that it is an area of non-combat, but with higher risks than are often associated with being located far from the fighting front. My thesis looked at 10 crash sites around Gander, recorded them, and researched each one to try to find the purpose of the flight, the crew on board (both those who survived and didn’t), what happened to cause the crash and if the archaeological record to tell us more, and what has happened to the aircraft since, and what is the condition of the crash site. I also conducted an excavation of the Globe Theatre on the Canadian side of the Gander airbase.

I have done other work around the province as well, including working with Mike on the recovery of a USAAF A-20 from Labrador, a quick survey of a Cold War crash near Goose Bay, another quick survey of a USAAF WWII crash on the Port-au-Port Peninsula, a detailed survey of the commercial crash of an American Overseas Airline DC-4, and a commission by the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s to record the crash of a 1978 Beechcraft in advance of the 40th anniversary of the fatal event. I also maintain a blog where I share my findings, plus do historical research about other aviation events around the province.

I have done other work around the province as well, including working with Mike on the recovery of a USAAF A-20 from Labrador, a quick survey of a Cold War crash near Goose Bay, another quick survey of a USAAF WWII crash on the Port-au-Port Peninsula, a detailed survey of the commercial crash of an American Overseas Airline DC-4, and a commission by the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s to record the crash of a 1978 Beechcraft in advance of the 40th anniversary of the fatal event. I also maintain a blog where I share my findings, plus do historical research about other aviation events around the province.

So, why Gander as an area of focus? Well, to do a study in aviation archaeology, Gander made perfect sense. It was the largest airbase in North America during the Second World War. Heavy bombers could make the trans-Atlantic crossing from the factories in North America to the war theatre of Europe by using Gander as a hopping point. Thousands of aircraft passed through Gander during the Second World War, and with so many aircraft, there were also accidents. The first one of note was the crash that killed Sir Frederick Banting in February of 1941. Not the first crash in Gander, but the first one with fatalities. A few months later, in July, an RCAF Digby crashed trying to land in poor weather, killing all on board (Also described in my chapter of the book Canadians And War Vol. 3). Throughout the war, there were numerous crashes, some with fatalities, and some without. Some were mechanical issues, many were weather related, and others were unsolved accidents. Those close to the airbase were typically recovered of all sensitive and useable material. Those further away had the few necessary items destroyed, and the remains of the aircraft were left on the landscape. As time went on, and Gander grew, some of those sites were impacted by highway construction, and accessibility allowed people to access them for scrap material.

My research took me to a variety of sites of different levels of preservation. For my thesis, I researched:

· RCAF Digby 742 which crashed in poor weather on return from patrolling the convoys. The site in very well preserved, thanks in part to its proximity to the Turkey Farm, or the Circularly Disposed Antenna Array, an area that can only be accessed with military approval.

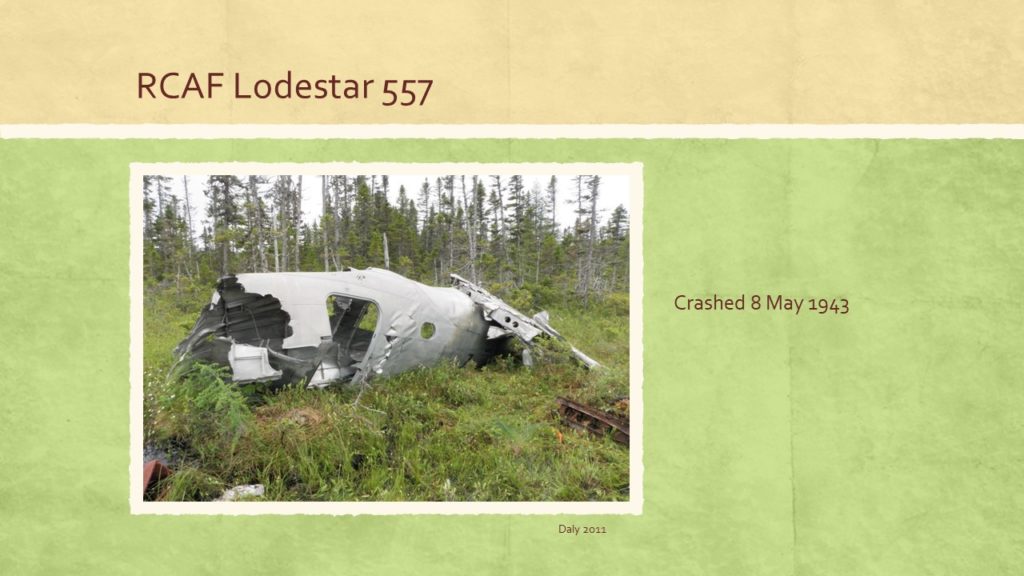

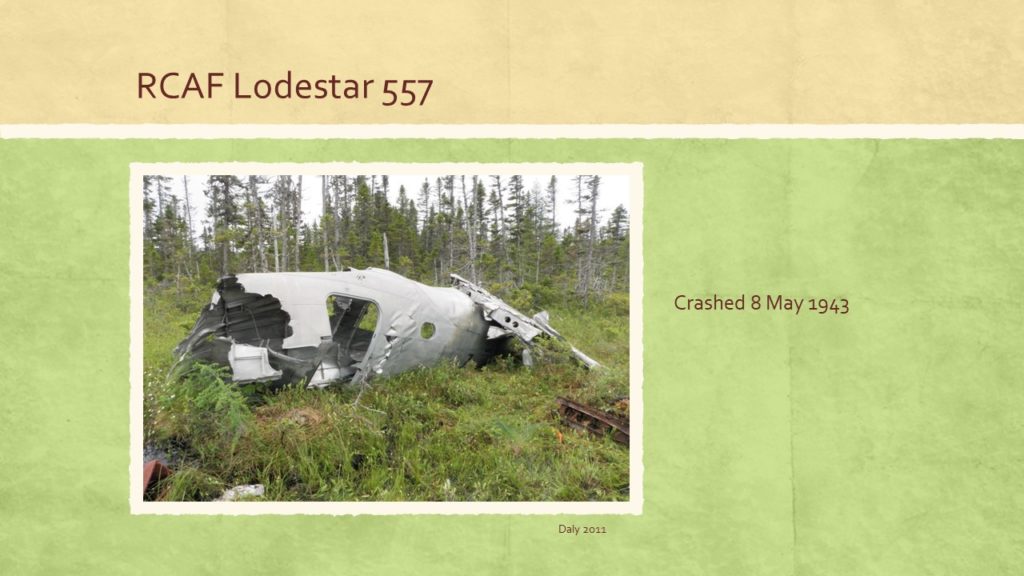

· RCAF Lodestar 557 was on a milk run when it crashed in poor weather, killing all on board. It is deep in a boggy area, and shows little evidence of being visited.

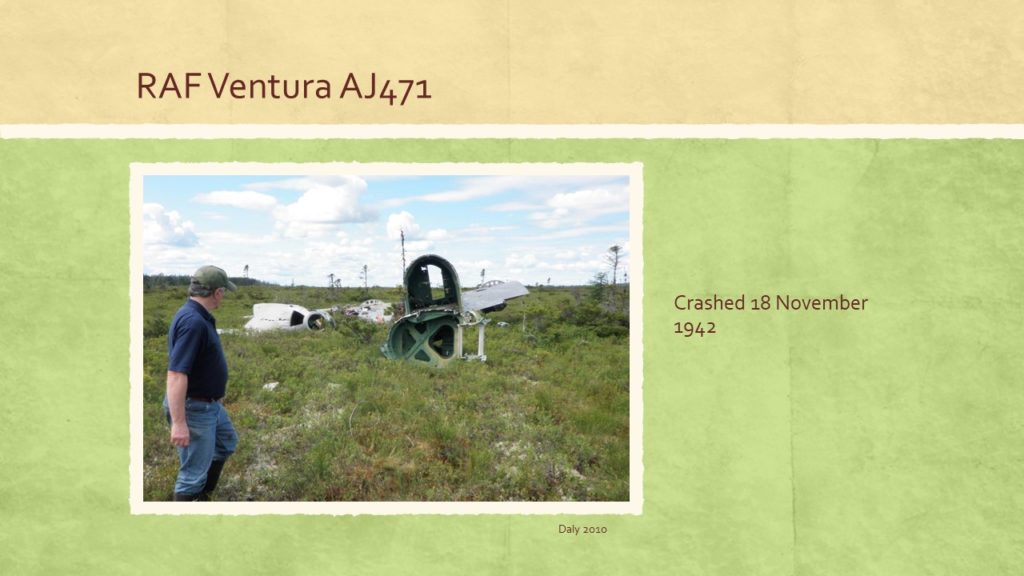

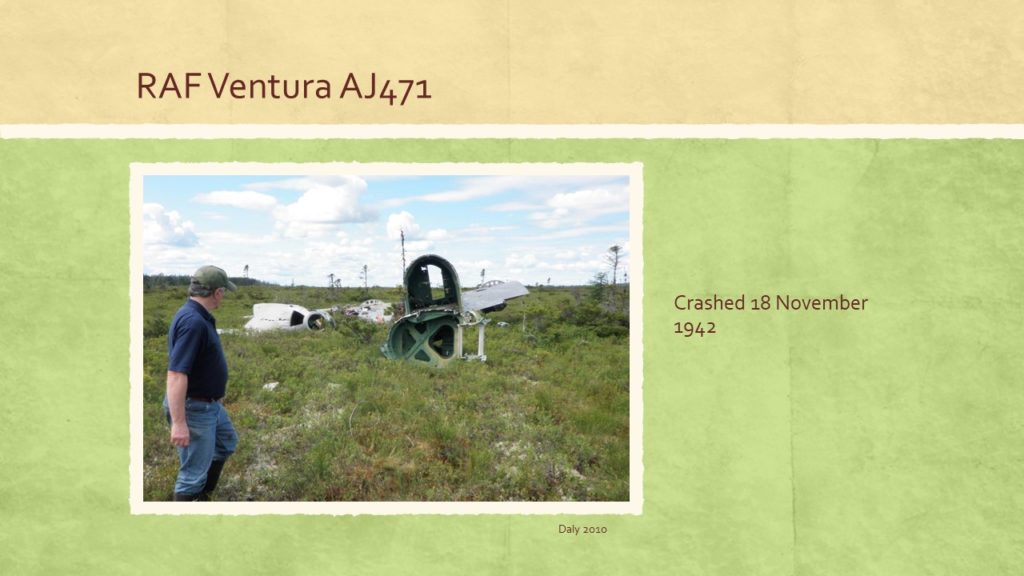

· RAF Ferry Command Ventura AJ471 which ran out of fuel and landed in a bog near Benton. The crew walked away from the crash, and the aircraft was close enough to the railroad that the engines and such could be sent back to Gander. This site is on a snowmobile trail, and is a target for graffiti.

· RAF Ferry Command Ventura AJ471 which ran out of fuel and landed in a bog near Benton. The crew walked away from the crash, and the aircraft was close enough to the railroad that the engines and such could be sent back to Gander. This site is on a snowmobile trail, and is a target for graffiti.

· RAF Hudson S/N FK 690 crashed for unknown reasons. The RAF records for this are lost, but two of the crew were Australian and their personnel records gave a little more information. The site has very little remaining as the Trans-Canada Highway was going to pass over it and locals were invited to take what they wanted from the crash site.

· RCAF Canso 98107 was leaving the airport when it exploded just beyond the runway, killing all but one on board. The aircraft was Canadian, but the Americans offered assistance both for the rescue effort and for the accident investigation.

· USAAF A-20 and RCAF Hurricane 5496. These two aircraft were in a mock dogfight over Gander when they clipped wings and crashed. The Canadian pilot survived, but all on the American flight died. The Canadian records have mostly been destroyed, only a crash card remains, but the American records discuss both aircraft.

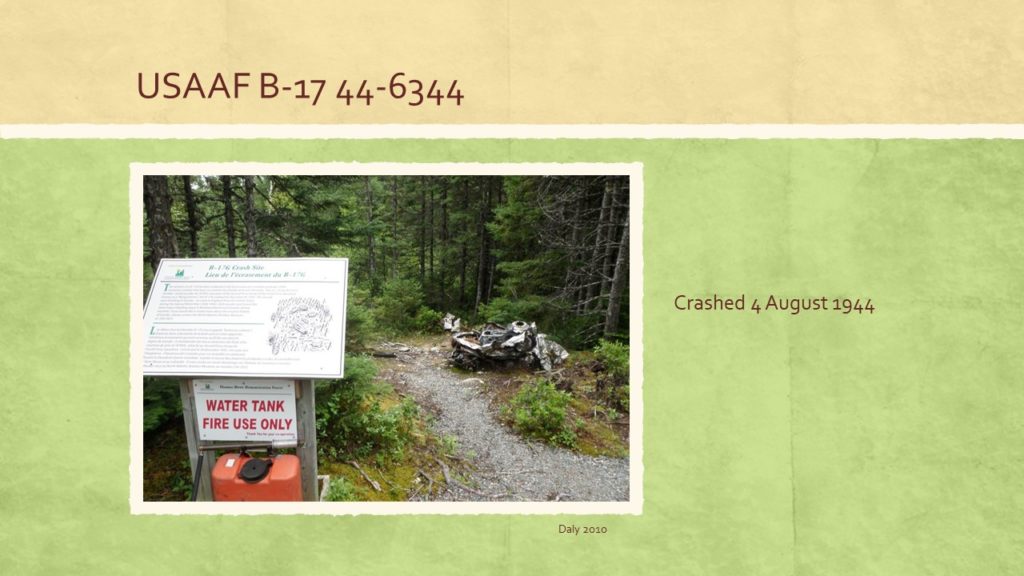

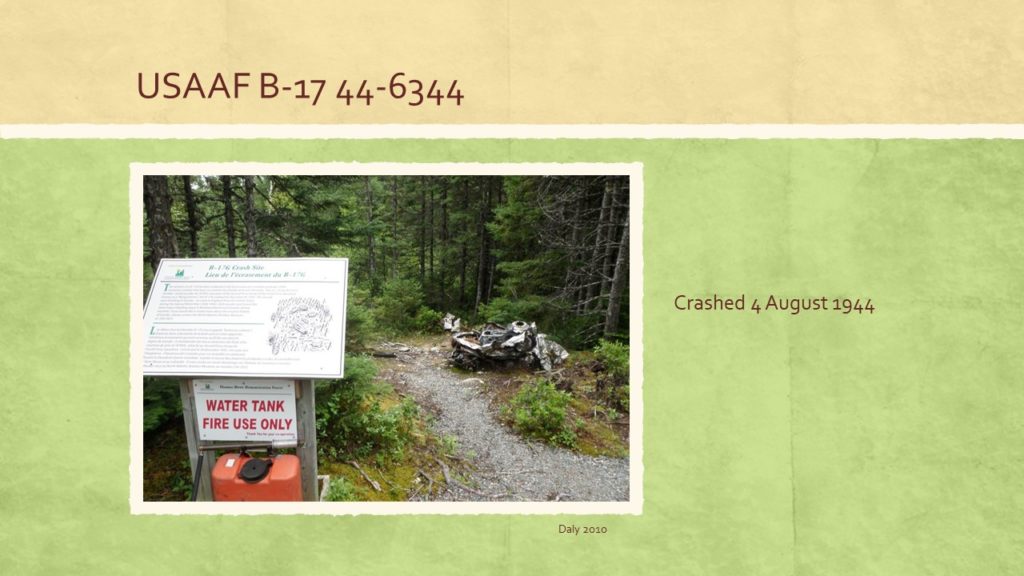

· USAAF B-17 44-6344 is another Transport Command aircraft that crashed for unknown mechanical reasons. It is very close to the previous one, but is protected by the Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest. Much of the wreckage was removed prior to the establishment of the Demonstration Forest, but what remains is now better protected.

· USAAF B-17 42-97493 was a ferry aircraft with Transport Command that crashed for unknown mechanical reasons. The highway passes very near the crash site, and the crash has been scavenged for all useable and sellable material.

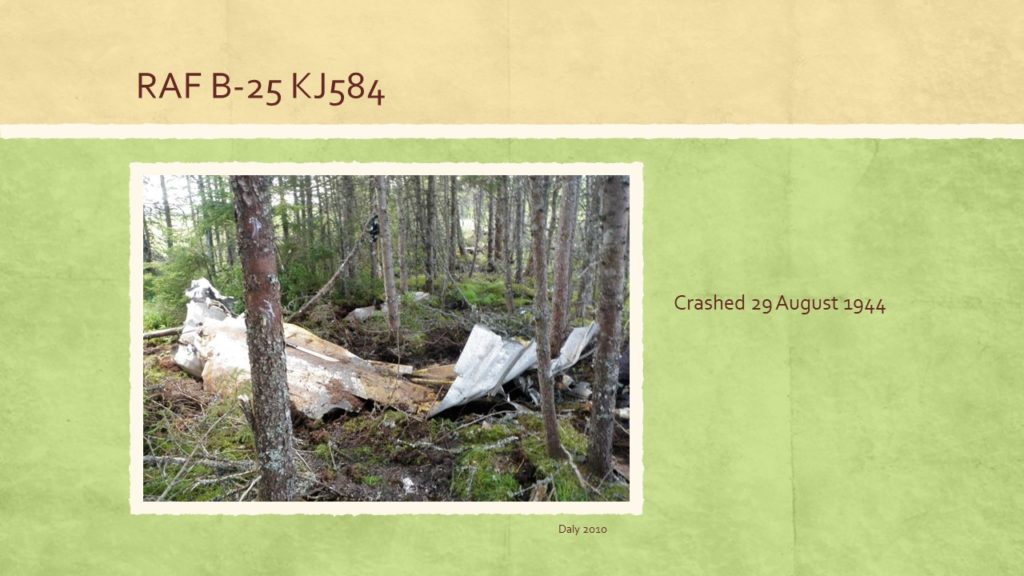

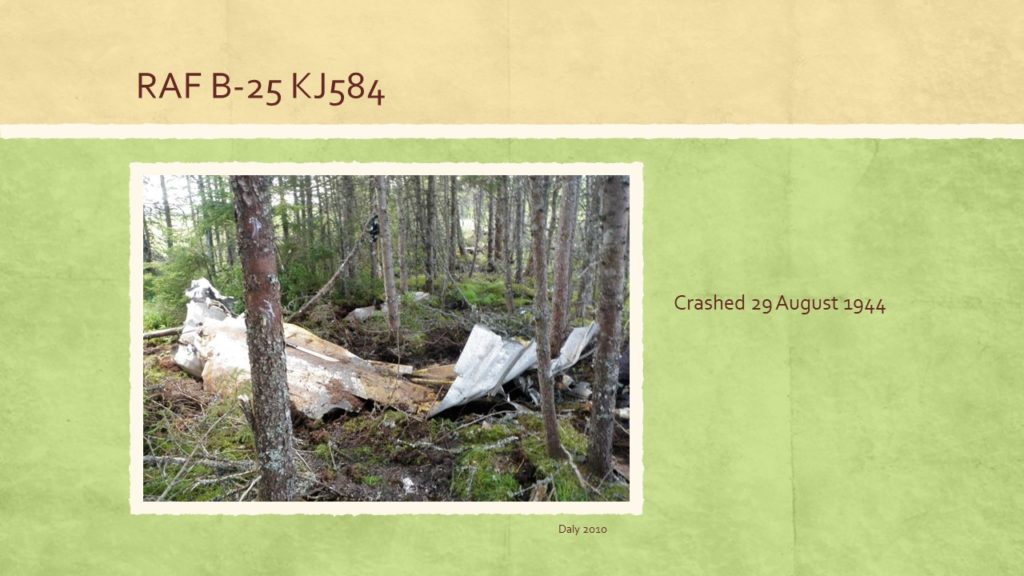

· Finally, RAF B-25KF 584 was a Ferry Command aircraft that crashed during a night takeoff. Interestingly, the two engines from the aircraft were left at the site, but were removed by 9 Wing Gander as a training exercise for the North Atlantic Aviation Museum.

In all of this, there were the people in Gander. This consisted of personnel for the Canadians, Americans, British, and the Newfoundlanders who were hired to build and maintain the base, and to work in some of the shops.

So, my starting point for any research, was actually to ask some of my contacts, like Darrell and Nelson Sherren, what they might know. But beyond that, my starting point was the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador. Back when I first started, I was working with the provincial government transcribing census records, and was given a digital copy of the 1945 record for Gander. It hasn’t been hugely informative, but a good starting place. Most of my time was spent looking through the GN boxes in the archives. These provide a wealth of information when it comes to the creation and growth of Gander. There are documents pertaining to airport expansion, costs, problems that have arisen, and the growth of the airbase into what eventually became the town of Gander. GN 4-5 Box 2 contains a number of crash reports, or at least the parts that were shared with the Newfoundland Commission Government. For instance, the official report for the American Overseas Airlines crash in Stephenville in 1946 is not present, but the Newfoundland Ranger reports and communications between the government and other parties, such as other governments and lawyers, are. As mentioned before, the crash that killed Sir Frederick Banting was one of the first on the island, and there is an extensive report spread between numerous sources, including GN 4-5 Box 2 and GN 13-1-B Box 398. Sometimes some digging is required, but the archivists have found some wonderful treasures for me that I didn’t even know I was looking for.

Within GN 38 Box S5-5-2 and S5-5-3, you’ll find a lot of documents relating to the construction of the base, such as cost overages, important visitors to the base, and infrastructure plans. After a while, I just skimmed many of those, but what is interesting when researching Gander is the relationship between Newfoundland and Canada. From the start, there was a fear that Canada would gain a foothold in Newfoundland with the construction of the base, and then with the arrival of the Americans, there was an even greater threat to Newfoundland sovereignty. For example, there are letters from the Commission Government reminding, in particular, the United States, that Gander did not fall under the Leased Bases Agreement in the same way that St. John’s, Placentia, and Stephenville did. Construction of the Gander Airbase had started before the start of the war, and so the Newfoundland Government had greater control of construction and expansion of the base. In St. John’s, Stephenville, and Placentia, the United States were allowed to expand as they saw fit. In Stephenville, this caused what was often called a shanty town to be built by Newfoundlanders looking for work just outside the perimeter of the base. The base expanded multiple times, and the locals did not bother to build anything of quality knowing that it was likely to be destroyed with the next expansion. Also of interest to the development of a community, was a letter from Governor Walwyn arguing that Newfoundland should only have to cover 1/6th of the cost of building and maintaining a school in Gander. In an undated letter, likely from 1944, Walwyn states that there are 57 school aged children in Gander, and had the base not been constructed there, there would be none. He argued that 46 of the children were of individuals directly employed by the airport, 8 were children of railroad employees, only present in such numbers due to the airport, 2 were children of the storekeeper, and one a child of the resident agent of the oil company, all only there because of their work at the airport. He argued that without an airport, there might only be a couple of children of railway clerks present, and they could easily be transported to a nearby community for school. The Commission Government felt that the Air Ministry in the United Kingdom should pay 5/6ths of the costs. The reply wasn’t in the record.

There are also a number of useful books pertaining to the US, Canada, and the UK during the war. Official histories are good resources, such as Douglas’s work The Creation of a National Air Force: The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force. This contains an entire section on Canada in Gander, mostly from the Canadian, not Newfoundland, perspective. Another that focuses on Ferry Command, one of the major roles for Gander early in the war, is Atlantic Bridge: The Official Account of R.A.F. Ferry Command’s Ocean Ferry put out by the Ministry of Information. Other official documents can be a little more difficult to find. In the Centre for Newfoundland Studies, you can find a couple of issues of Proppaganda, and PropperGander, which were USAAF publications. Proppaganda was the title used before the base location was known, and once the name Gander was known for the airbase, they changed the name. On the RCAF side, they had The Gander, of which I believe there are copies in the CNS, but I mostly found online on file sharing sites (I had to put up something to share to be able to download them). I have since given copies to the North Atlantic Aviation Museum and Gander Airport Historical Society and they have put them online. Both of these publications are official magazines put out by the military, contributed to by those living in Gander. These are publications to be sent back home, so they are sanitized, but also reflect the attitudes of the militaries. The Gander often focuses on recreation and personal, silly stories, whereas Proppagander is really just that, much of it talks about how “the girls in Newfoundland are just like the girls at home” and how the Americans serving on base would be an example to the other countries serving and working in Gander.

Unofficial histories are also readily available, at least through inter-library loans. Perhaps one of the most important books for researching the early days of the Newfoundland Airport would be Pathfinder by D.C.T. Bennet. Bennet was an Australian serving with the RAF who was tasked with determining if aircraft could be ferried by air rather than by sea. Early in the Second World War, aircraft would be built in Canada or the US, tested, disassembled, packed in crates, loaded on ships, and sent with the convoys crossing the Atlantic. This was a lengthy process, and high risk, as each ship lost to U-boats could mean multiple aircraft lost. Lord Beaverbrook, born in New Brunswick, was the Minister of Aircraft Production in the UK, and determined that losses were high enough that if seven bombers were flown in an experimental crossing, and three of those bombers successfully made it across, it would be feasible to simply fly the aircraft instead of shipping them. Bennett hand-picked crews for 7 Hudson bombers, and oversaw modifications to the fuel tanks to ensure they had enough to get across the ocean. On November 10th, 1940, seven crews made up of twenty-two men, and seven bombers, led by Bennett, left Gander and arrived safely on November 11th in Scotland. The crews were greeted and handed poppies in honour of Remembrance Day. This was the beginning of Gander’s new role as the hub of trans-Atlantic aviation. Bennett’s story is well covered in his own memoir, Pathfinder, but also discussed in Ocean Bridge by Christie. As I will discuss later, this book is much relied upon for researching the RAF in Gander.

One of the wonderful things about working is Gander, or Newfoundland and Labrador in general, is that there are no shortage of memoirs available. We are certainly storytellers around here, and we all have our own stories to tell. A look around the gift shop in the North Atlantic Aviation Museum shows a number of memoirs that have been published by those affiliated with the airbase, and these are all wonderful resources to really understand what life was like for Newfoundlanders on the base and in early Gander after the war.

When researching anything related to the United States Army Air Force, it is possible to request information directly from the Freedom of Information Act, but that can be a time consuming and tedious process, often having to defend why you are looking for that information, and when you do get it, it is often heavily redacted. The best source I have found is to use AAIR (Aviation Archaeology Investigation & Research at aviationarchaeology.com). The website is run by an individual with interest in aviation archaeology, and US aviation history. He has spent time copying the old incident reports from various archives, and will share them for a reasonable fee. When I first started my work, his costs were higher because he needed to send out physical copies of everything, including pictures. Now even large files can be easily sent through file sharing programs and the fees are considerably less. They are still based on the size of the report. For instance, he sent me a short version of the incident report associated with the crash of the B-36 in Burgoyne’s Cove, because the full report would be almost $100.

These reports typically contain pictures from the crash, witness reports, and the official investigation into the crash.

I, personally, haven’t looked into individual files, but if you check out Darrell Hillier’s thesis, he does look into the amount of information that can be obtained about the people who served, even without the official documents as those related to the crew he was researching were destroyed in a fire. Records can be requested through the National Archives, but I do not know how detailed those might be.

Similarly, the Royal Air Force personnel records are only available to next-of-kin. Coupled with that, many of the records were destroyed, so it becomes difficult to research those crashes. Ocean Bridge is the best starting point for RAF records. Christie’s book not just goes through a detailed history of Ferry Command, complete with discussion of some of the major incidents, but in the back of the book is a run-down of all Ferry Command crashes. There is not a lot of information on each crash, but there is usually an indication of what happened and a list of the crew. The best resource for RAF resources are the message boards, specifically the RAF Ferry Command Forum. There is a lot of information on these forums, and a lot of helpful historians willing to share information.

One of the resources I did use in researching one of the RAF sites were the Royal Australian Air Force records. The pilot and radio operator on RAF Hudson S/N FK690 were with the Royal Australian Air Force, so even though British and American records are sealed, I contacted the National Archives of Australia, and for a price, they will send records. I requested those of the pilot, Ronald George Stanley Burrows, and received a link to a digital copy of his records. The file contained his death certificate, a brief on the incident, letters to and about his wife, and a beautiful letter from someone who visited the graves of the Australians in the Commonwealth War Graves in Gander. Unfortunately, the picture of the grave was not included (so I included my own here).

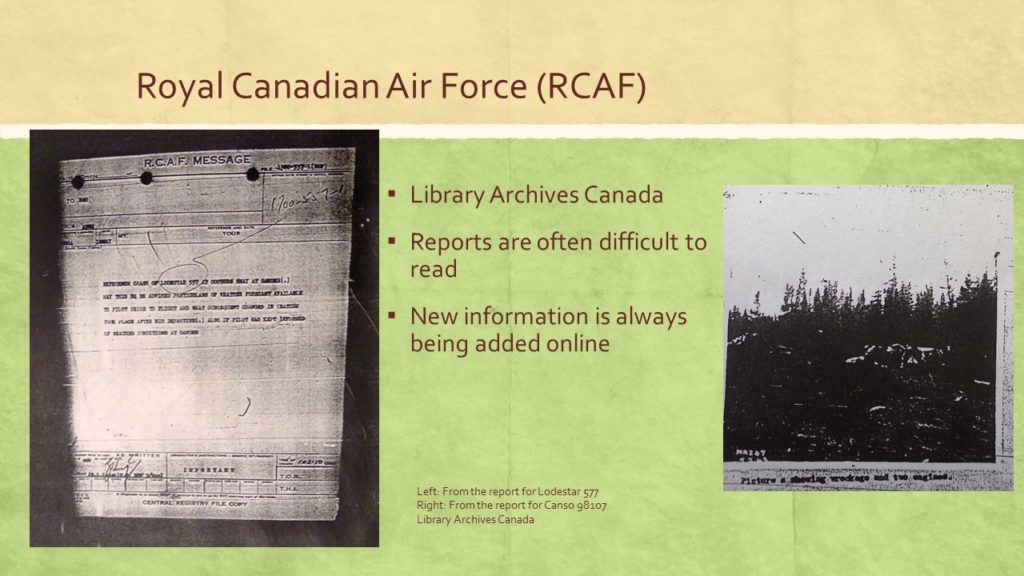

Last on the list for official records would be the Royal Canadian Air Force. These are available through Library Archives Canada. Since I started, a lot of it has been digitized and is much easier to access. For instance, the Base Diaries are online, which list incidents of note. When I started this work, I had to request microfilm through the MUN library inter-library loan service, then sort through the film in the basement of the library. It was slow going as the records were done with saving space in mind. Reading one way, we see one set of records, and turning it around, we get another. Which means the records are not the clearest, even for microfilm. Coupled with that, I was not always given accurate information about what was on the reels, so sometimes had reels I didn’t need, or, in other cases, found reports I wasn’t specifically looking for but copied anyway, including that of the B-24 in Gander Lake (which is by far the most difficult to read of all the records). Thankfully, now many more of the records are digitized, and, if it is not, they will offer to digitize it for a fee.

These tend to be full reports, like the USAAF ones I mentioned earlier. So they contain witness reports, and the full investigation. There are also pictures, but they are typically very poor quality. I did find that they will suggest using a researcher for larger or more complicated files.

Outside of the individual crash sites, if you are researching life in Gander throughout and just after the war era, the best resources are probably the magazine I suggested earlier (The Gander and Propergander) and the memories of Newfoundlanders. Again, as I said before, there are a wealth of memoirs published about Gander, each of which gives their own perspective on growing up or living in Gander. There are a few unpublished ones as well, or some that are online on the Gander Airport Historical Society page. The Gander Library has binders full of newspaper clippings about the area (though these are not always well sourced). The local newspapers have a wealth of information. When researching Gander, I was turned on to the Grand Falls Advertiser as a great resource. American and Canadian service men and women would take the train to Grand Falls for social events throughout the war. Fewer Americans went when the USO opened in Corner Brook, but the Canadians often frequented Grand Falls. Their “adventures” often made it to the gossip columns. One in particular I enjoyed gossiped about how one local lady in Grand Falls went out for a date, but when her date was running late due to a flat tire on his bicycle, one of the RCAF servicemen who happened to be in the area kindly stepped in to take his place. While there are often proper articles about some of the events that happened in Grand Falls, the best information could be found in the gossip columns.

Of course, the best information comes straight from the community. Attending museum events, giving talks then talking to people, or even conducting excavations in Gander, I had the pleasure of talking to so many wonderful people who were always happy to share a story. In fact, it seemed like there were so many stories in and around Gander that I could never manage to hear them all, and we’d end each visit with “next time I’ll tell you about…”.

So, as I said when I started, I started this work back in 2007 and the way to research it has changed quite a bit since then. As I’m sure we all remember, Library Archives Canada had some difficulties about a decade ago I’m sure we all remember the cutbacks to Library Archives Canada, and the absolute lack of access to anything. Thankfully, that is improving all the time (although their site is still awful to navigate and I have trouble finding the same documents two days in a row). PANL and the Digital Archives are always great resources, and their ease of access means I can do a lot of my research from anywhere. For instance, when I came across a site on the Port aux Port and wanted to know more, I contacted the fellow who runs aviationarchaeology.com, gave him the site information I had from the interpretation panel, emailed him a few dollars, and within an hour had a pdf of the incident report with pictures, and combined that with my own site pictures to create a presentation for the Stephenville Regional Museum of Art and History a couple of days later.

There are also a lot of researchers out there, and some are online. A great resource is the Gander Airport Historical Society who have been sharing articles, resources, and a lot of pictures of Gander. Their website is a great resource, and their twitter shares pictures every day. If you are doing any research about the area, reach out to them or the North Atlantic Aviation Museum and I am sure they will lend a hand.

I hope this gave an overview of the resources available for doing Second World War research. This focused on the research I did around Gander, but is applicable for the province, or really any Second World War aviation research for Allied sites. I have not needed to look into researching other countries, even though there were other Allies who passed through Gander. I, personally, am always finding new resources, and the internet is always making the records more accessible.

Much of my research especially that around Gander, also falls under the heading of conflict archaeology, which is the archaeological study of human conflict. Gander is a special case in conflict archaeology, in that it is an area of non-combat, but with higher risks than are often associated with being located far from the fighting front. My thesis looked at 10 crash sites around Gander, recorded them, and researched each one to try to find the purpose of the flight, the crew on board (both those who survived and didn’t), what happened to cause the crash and if the archaeological record to tell us more, and what has happened to the aircraft since, and what is the condition of the crash site. I also conducted an excavation of the Globe Theatre on the Canadian side of the Gander airbase.

Much of my research especially that around Gander, also falls under the heading of conflict archaeology, which is the archaeological study of human conflict. Gander is a special case in conflict archaeology, in that it is an area of non-combat, but with higher risks than are often associated with being located far from the fighting front. My thesis looked at 10 crash sites around Gander, recorded them, and researched each one to try to find the purpose of the flight, the crew on board (both those who survived and didn’t), what happened to cause the crash and if the archaeological record to tell us more, and what has happened to the aircraft since, and what is the condition of the crash site. I also conducted an excavation of the Globe Theatre on the Canadian side of the Gander airbase. I have done other work around the province as well, including working with Mike on the recovery of a USAAF A-20 from Labrador, a quick survey of a Cold War crash near Goose Bay, another quick survey of a USAAF WWII crash on the Port-au-Port Peninsula, a detailed survey of the commercial crash of an American Overseas Airline DC-4, and a commission by the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s to record the crash of a

I have done other work around the province as well, including working with Mike on the recovery of a USAAF A-20 from Labrador, a quick survey of a Cold War crash near Goose Bay, another quick survey of a USAAF WWII crash on the Port-au-Port Peninsula, a detailed survey of the commercial crash of an American Overseas Airline DC-4, and a commission by the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s to record the crash of a