I ordered Atlantic Fever: Lindbergh, His Competitors, and the Race to Cross the Atlantic by Joe Jackson through my local library as research for a project I am working on. I was looking for one aviator that I did not know much about, but found this wonderful, detailed book of all of the aviators who were involved in the race for the Orteig Prize, ultimately won by Charles Lindbergh when he flew from New York to Paris in 1927.

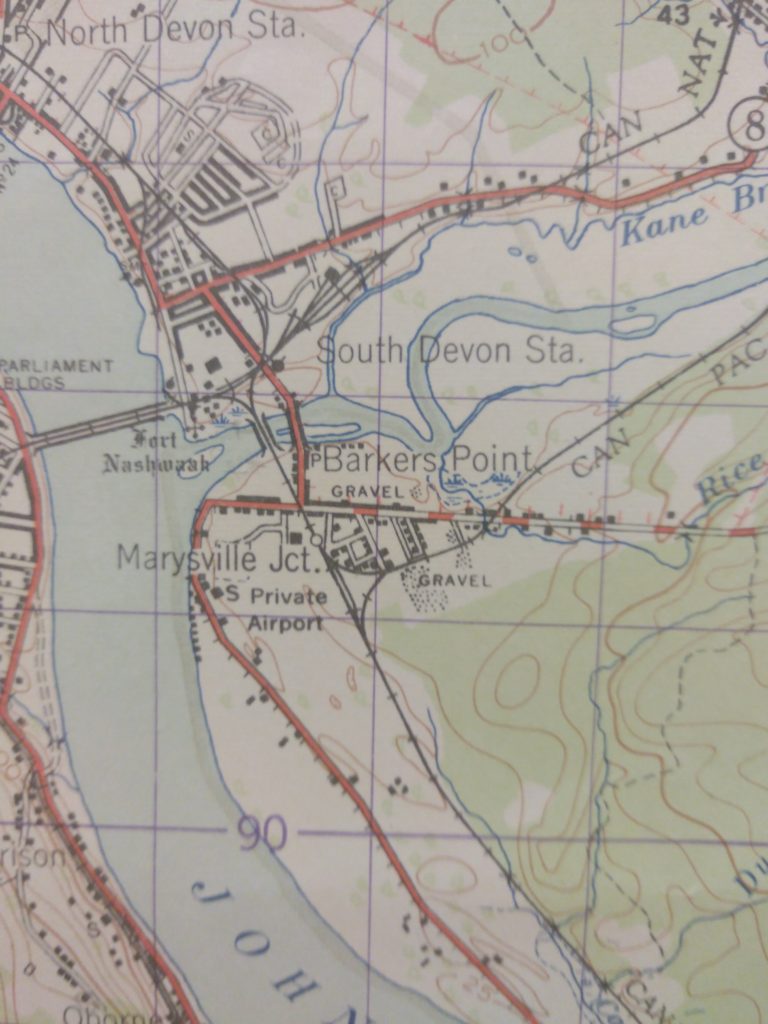

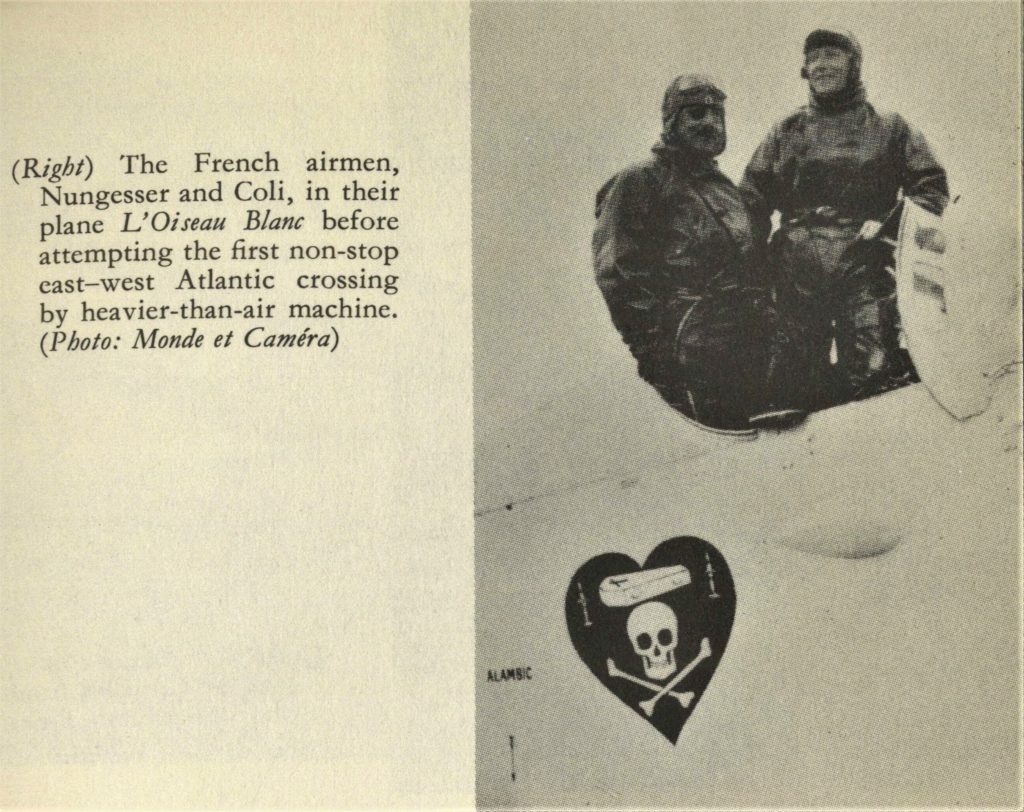

I found this text to be interesting, as I had not really thought much of the Orteig Prize, as most of my focus is on Newfoundland and Labrador specific aviation. That said, even in reading this, I did make note of anything related to Newfoundland. Funny enough, almost all of the aviators in the book do have a Newfoundland connection. Lindbergh used Signal Hill to check his instruments on his historic flight, the Columbia landed in Harbour Grace twice, once as part of the first Canadian transatlantic flight, and the Oiseau Blanc may have been lost near, or as some speculate, on the island of Newfoundland. In fact, Jackson talks about how the loss of the Oiseau Blanc delayed some of the other aviators on their attempts for the Orteig prize until Nugesser and Coli were found, and how the search for the Oiseau Blanc is still ongoing. While I have not focused on the French aircraft, I do make note of archival documents that mention it and stories that offer theories on where the aircraft might have crashed, and, in 1992, TIGAR were in Newfoundland searching, likely based on much of the same information.

One theory Jackson puts forward is that the Oiseau Blanc was a casualty of American Prohibition, being shot down by the rum boat Amistad, off the coast of Saint Pierre and Miquelon. I had not heard that theory before, but, interestingly enough, had recently had a hand in the selection of stories for Flights From The Rock by Engen Books, and one of the stories is eerily similar.

One thing I did find interesting about the book was how much more detail there was in Lindbergh’s preparation. When reading We a while back, the autobiographical book made it sound like Lindbergh, on a whim, picked up the Spirit of St. Louis on a whim and few across the Atlantic. In fact, Jackson details the financial wrangling, as well as some of the meetings that Lindbergh had, and the sometimes struggles he had to secure not just funding for the aircraft, but also to ensure that he, and he alone, would fly the aircraft. It wasn’t just hubris, but Lindbergh, unlike the other aviators in and around New York, believed that a smaller, lighter, aircraft would be best for the flight, while the others were experimenting with large, tri-motor aircraft and crews of at least two. It also detailed how the aviators, Lindbergh included, had to watch the weather around Newfoundland, worried about the fog and pressure systems known to cause problems around the Grand Banks. While these flights were to leave New York, Newfoundland would be the last point of land, and watching the weather was imperative for any flight.

Of course, while the book offers a lot of very interesting and very useful information, there are some problems. The big one, from my own perspective, is that it does not recognize that Newfoundland was not part of Canada, and it uses Newfoundland and Canada interchangeably. Certainly, Newfoundland and Labrador are now part of Canada, but to the aviators in question during their transatlantic bids, as well as later for their flights to Harbour Grace, they were in Newfoundland, not Canada. It might be a small thing, and it can sometimes be difficult to reconcile where Newfoundland and Labrador history fits within Canadian history, having joined the country only in 1949, but, as a researcher, it makes it easier when looking for specific things to acknowledge that distinction.

The author also seemed to be sort of star-struck by the aviators. This is understandable, and easy to do when conducting this research. The attempts for the Orteig prize was highly publicised, and, whether they wanted to be or not, the aviators were taken up as media darlings. In fact, as Jackson points out, some conflicts arose when selecting crews, as sometimes the more “Holywood” or “attractive” potential crew member was sometimes selected over other, equally qualified aviators. Jackson’s language reflects this media frenzy with a lot of descriptions about the appearances of the aviators, and if they were thought of as attractive at the time. It is very much a product of that media frenzy that did often focus on looks, and not always the merits of the aviators. That said, Lindbergh, while being considered incredibly all-American attractive at the time, was an astounding aviator, and did quite a lot to use his fame to promote aviation.

It was also very nice that the book looks at the aftermath of the Orteig prize. Many histories (and I myself have done this) don’t bother to look beyond the big event, but Jackson followed the other aviators involved and told how the Columbia and the America continued their attempts, and crossed the Atlantic with varying degrees of success, as well as other aviators who made the attempt in the years that followed, especially the women who tried to be the first to cross the Atlantic.

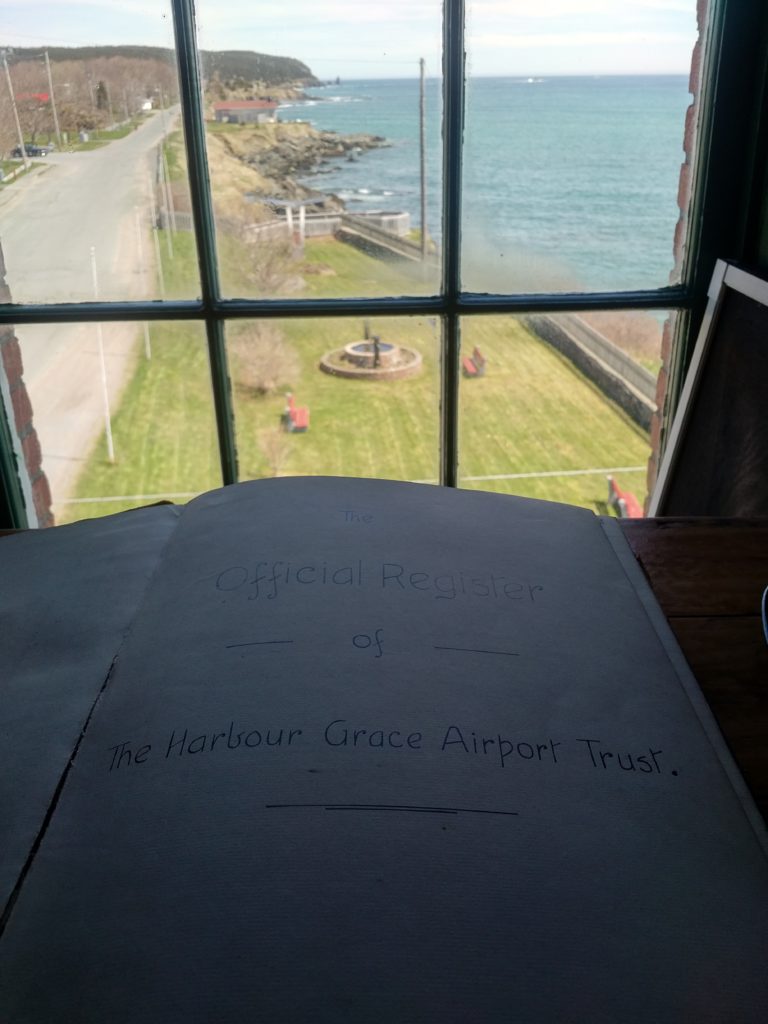

Overall, this is a very good and informative book that I would highly recommend for anyone interested in early aviation. It is large and long, but filled with a great deal of information that I have yet to disseminate for my own research. I will certainly be referring to the notes I made, and may likely pick up my own copy at some point, rather than the library copy I read this time around. Perhaps my favourite part of the book is seeing all of the names that I have seen before in the Harbour Grace Airfield Log Book, as many of them stopped in Harbour Grace on other flying adventures.

Sources:

de la Croix, R.

1959 They Flew The Atlantic. W.W. Norton & Co. Inc.: New York.

Jackson, J.

2012 Atlantic Fever: Lindbergh, His Competitors, and the Race to Cross the Atlantic. Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York.