Another stretch where I just couldn’t get to the blog. I have been preparing for some conferences. This Friday is a Public Archaeology Twitter Conference. I will be the last presenter of the day, at 23.15 GMT presenting the paper “Preserving Aviation Archaeology Sites While Engaging Public Interest: A Discussion with Gander, Newfoundland, as a Case Study”. If you want to follow the conference, check out #PATC and for my paper discussion, follow me at @planecrashgirl. This should be an interesting experiment in conference presentations, and a wonderful way to make academic papers more accessible.

Time for a book review.

A wonderful friend of mine gave me one of the most amazing gifts I have ever received: a well-loved copy of Charles A. Lindbergh’s “We”: The Famous Flier’s Own Story of his Life and his Transatlantic Flight, Together with his Views on the Future of Aviation. When he gave it to me, he called it his prized possession and wanted me to have it. Thinking about how much this gift means continues to make me a little emotional to know that I have such amazing support in my research. Thank you Nelson.

I know there is very little about Newfoundland in this book, but Lindbergh does mention Newfoundland and flying over on his historic trans-Atlantic flight. Plus, he did visit Newfoundland a few times on his flights, or at least fly over.

“We” is a very interesting read from the perspective of aviation history. Lindbergh is not a strong writer, in fact, he feels that he is at a loss for words when it comes to talking about the celebrations and fanfare surrounding his trans-Atlantic flight and brings in Fitzhugh Green to write about the speeches and fanfare.

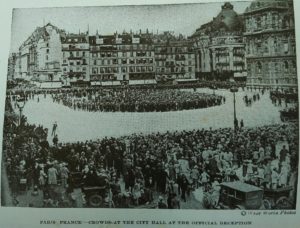

From Lindbergh 1928

Throughout Lindbergh’s book, the focus is so much more on his early flying career; his training, barnstorming, and his time training for the reserves. He devotes very little to the planning and preparation of his trans-Atlantic flight. In fact, if you were to read it without Green’s section, it almost seems like the flight is a bit of a whim instead of months of planning. Certainly, he talks about how he changed the aircraft to carry more fuel, some of the testing, and his route planning, but it is all done in very little details when compared to his stories about barnstorming or his crashes and accidents.

From Lindbergh 1928

What Lindbergh’s book is really interesting for is his descriptions of early flight training, and the novelty of aircraft in different areas of the United States. He spends a lot of time barnstorming and working fair circuits to make some money, and has some great stories where people come together around the novelty of aircraft (communities pitching in to allow a coloured individual to fly, pulling the aircraft out of a ditch, or even forgiving damages to a storefront as it would be great advertising for the shop!). He talks more about his first plane (a military auction Jenny) than the other half of we in “We” (Spirit of St. Louis).

From Lindbergh 1928

What is of particular interest for any aviation historian is his in-depth look at training to be in the Army Air Corps Reserves. He devotes a lot of the text to the ins and outs of training, the trouble they sometimes got up to, and has his one accident report copied verbatim.

Lindbergh offers up insights and theories on aviation, many of which came to be in the next few years, such as the importance of parachutes and the capabilities of aircraft. He continuously refers to the short period of invention to improvement of aircraft and envisions almost limitless journeys in all kinds of weather. While flying at night and in poor weather has much improved, there are of course still the weather extremes that can stop flights. But, as Lindbergh predicted, these are always improving (see YYT and their new measures to help flying in the fog). The only one I think he really missed the mark on was discussing commercial aviation, but then, he talks about the potential for commercial aviation with small aircraft in mind, and for many years, commercial aviation was incredibly viable as a luxury venture with small aircraft. Now, with the larger aircraft, and discounted rates, it seems to be a whole different creature than what could be envisioned with the small aircraft of the 1920s.

From Lindbergh 1928

Sources

Lindbergh, C.A.

1928 “We”: The Famous Flier’s Own Story of his Life and his Transatlantic Flight, Together with his Views on the Future of Aviation. Grosset & Dunlap Publishers: New York.

From Lindbergh 1928