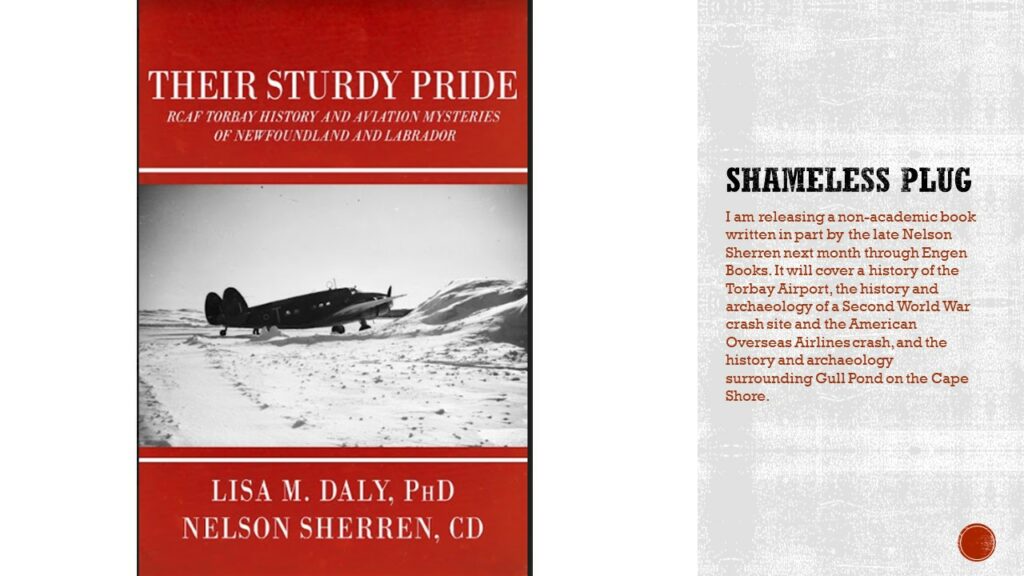

While I haven’t been posting, I’ve been working hard. I have been working on a peer-reviewed article for the Journal of Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, and finishing my book with Nelson Sherren, Their Sturdy Pride, which is now in the hands of my publisher, Engen Books, for layout. It should be available very soon, though not likely in time for Christmas. This past month I also gave two presentations, one at the Newfoundland and Labrador Archaeological Society symposium and another at Avalon Expo. This is the presentation I gave at NLAS.

An overview of some of the aviation archaeology that has been done in Newfoundland and Labrador. Areas of study include early aviation such as the search for the Oiseau Blanc lost in 1927, through the Second World War with a focus on Gander, to early commercial travel in 1946, and community focused stewardship of a 1978 crash site. Finally, a brief look at why aviation archaeology goes beyond wreck chasing to become a legitimate area of archaeological study.

Most early aviation work in Newfoundland and Labrador is historical research. Little material culture remains from the 1919 Air Race which saw aviators come to Newfoundland to try to be the first to make a non-stop flight across the Atlantic and win the Daily Mail prize of £1,000. What remains are parts of the aircraft, housed in museums, and numerous pictures.

The Great Atlantic Air race recognized that, due to its geography, Newfoundland was the best hopping off point for transatlantic flights. Where it juts out into the Atlantic, it reduced the distance needed to fly, and, later when aircraft attempted to take off from other areas, they would still often fly over Newfoundland. For example, on Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight from New York to Paris to win the Orteig Prize, he flew over Signal Hill, and the Hindenburg passed over Newfoundland multiple times during transatlantic crossings.

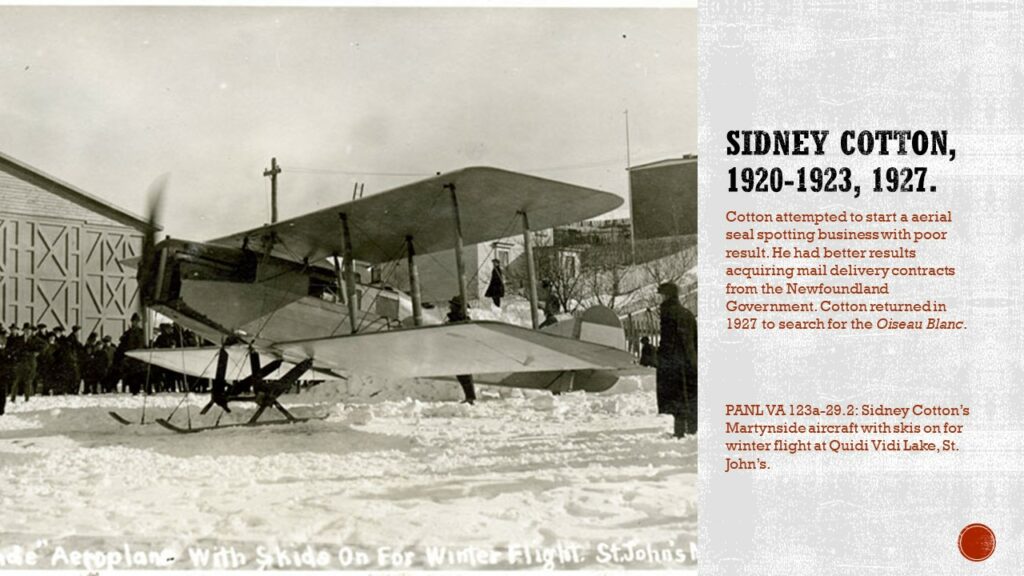

In the 1920s, aircraft became a more common sight in Newfoundland as Sidney Cotton attempted to start aerial seal spotting and mail delivery, which mixed success. But his aircraft were seen around Newfoundland and into Labrador.

My archaeological work starts with sites potentially dating to 1927.

In 1927, before Lindbergh made his historic flight, others were trying to win the Orteig Prize, including Nungesser and Coli in the Oiseau Blanc, two decorated French aviators. They left Paris on May 5th, 1927, and never made it to New York. An extensive search was conducted for the missing aviators. Searches occurred along the Irish coast, in Maine, northern Quebec, Saint Pierre, and Newfoundland. Ships were told to be on the lookout for the aviators or any airplane wreckage. In 1919, two aviators, Hawker and Grieve, ditched in the ocean and were picked up by a ship, so many were hopeful that this would happen for Nungesser and Coli. In July of 1927, Sidney Cotton returned to Newfoundland and did an extensive search of the island, and into Labrador and Saint Pierre, but no trace of the aviators were found.

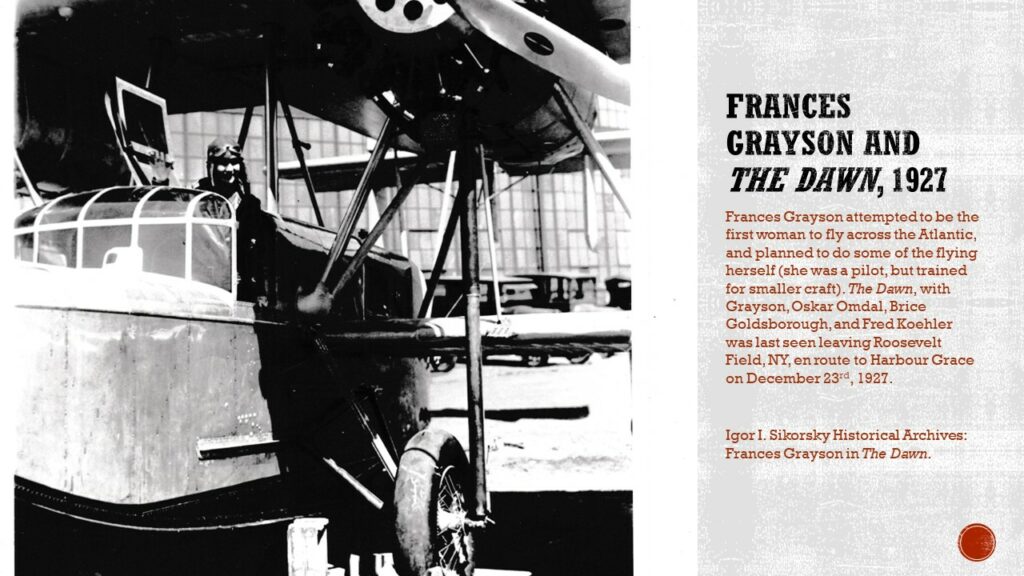

Later that year, aviatrix Frances Grayson made an attempt to be the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air. After a few failed attempts in October 1927, Grayson had her aircraft, The Dawn, repaired and made another attempt in December. She and her crew left Old Orchard, Maine, and were never seen again.

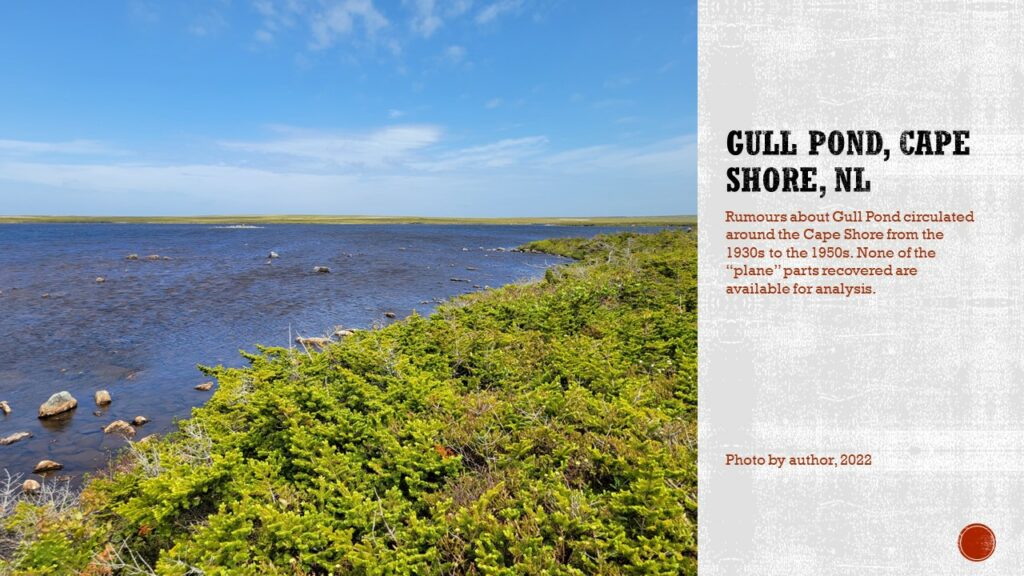

In both cases, the Oiseau Blanc and the Dawn were said to have been sighted over Newfoundland, and there are signed affidavits at the Rooms from those who witnessed the Oiseau Blanc. About a decade later, stories start around the Cape Shore of aircraft remains in a pond. The stories say the aircraft pieces were painted blue, and some of this aluminum was removed from Gull Pond in the middle of the Cape Shore. Since then, every piece that was removed or found at the site, seems to have disappeared or been destroyed, so there are only stories left.

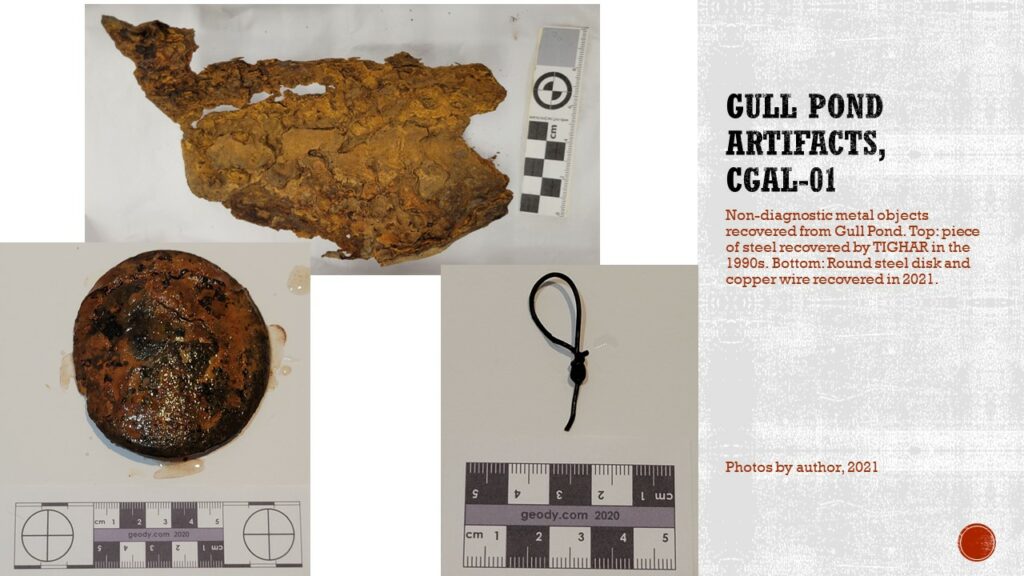

Archaeology was conduced around this pond in the 1990s by a group called TIGHAR. A local group also tried to investigate the site at the same time, but didn’t have an archaeologist to be able to obtain a permit, and local archaeologist Roy Skanes was already working with TIGHAR. In their search, TIGHAR found a piece of metal and made claims that it was likely from the Oiseau Blanc.

I visited the site a couple of times, first with the television show “Expedition Unknown” as the on-site archaeologist, then with TIGHAR who wanted to further investigate the site. With Expedition Unknown, two more objects were recovered from the edge of a small island in the pond, though there is still no evidence that these belong to an aircraft. In June 2022, I went out again with TIGHAR who wanted to survey the pond to come back with underwater archaeologist Ken Keeping (we were acting as partners for this project), but they found the waters too rough and shallow for diving. Having walked some of the perimeter of the pond and investigated outflows, there is a lot of evidence that people use the area (we found pop cans and Vienna Sausage cans) but nothing indicating an aircraft ever crashed into the pond.

Overall, while the fate of the Oiseau Blanc and the Dawn are still mysteries, and I am certain people will continue to search for them.

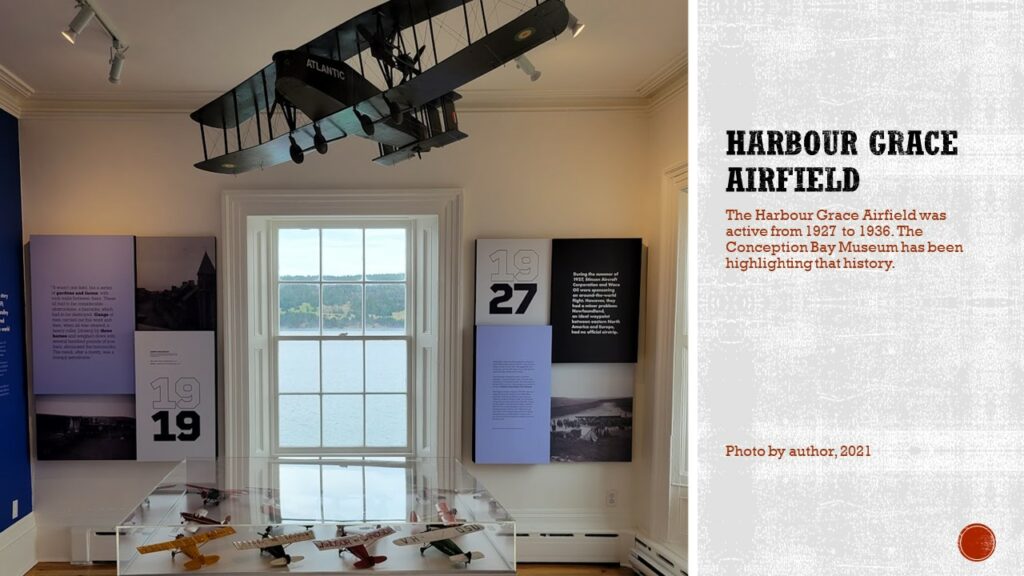

I have been doing work with the Conception Bay Museum and their aviation history, such as the many flights that used the Harbour Grace Airstrip from 1927 to 1936, and I know there was a walkover done by the PAO on the airstrip at one point, but right now my work in that area has been strictly documentary, but I do encourage everyone to visit their aviation exhibit that I recently helped update, or their digital exhibit on Digital Museums Canada.

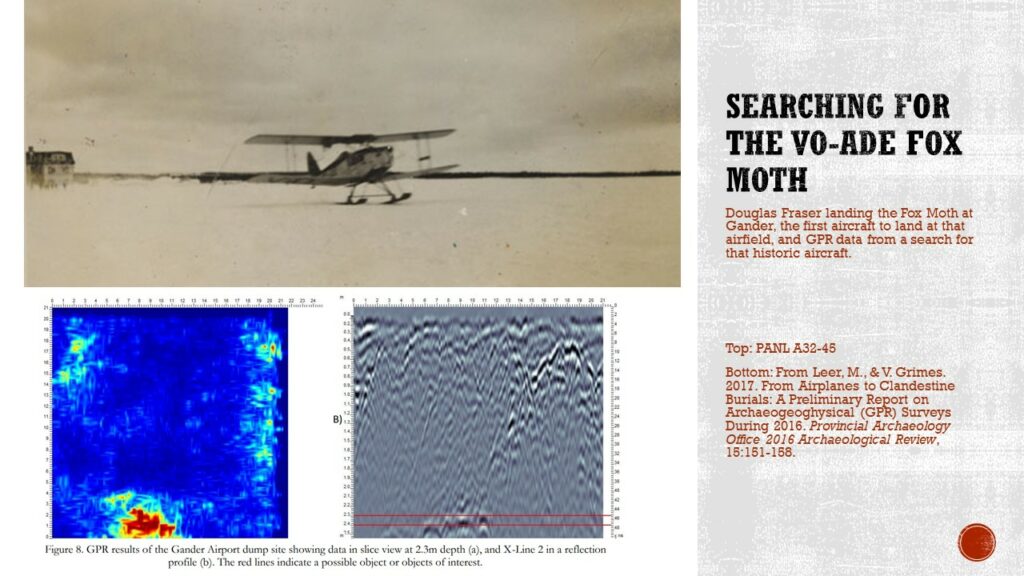

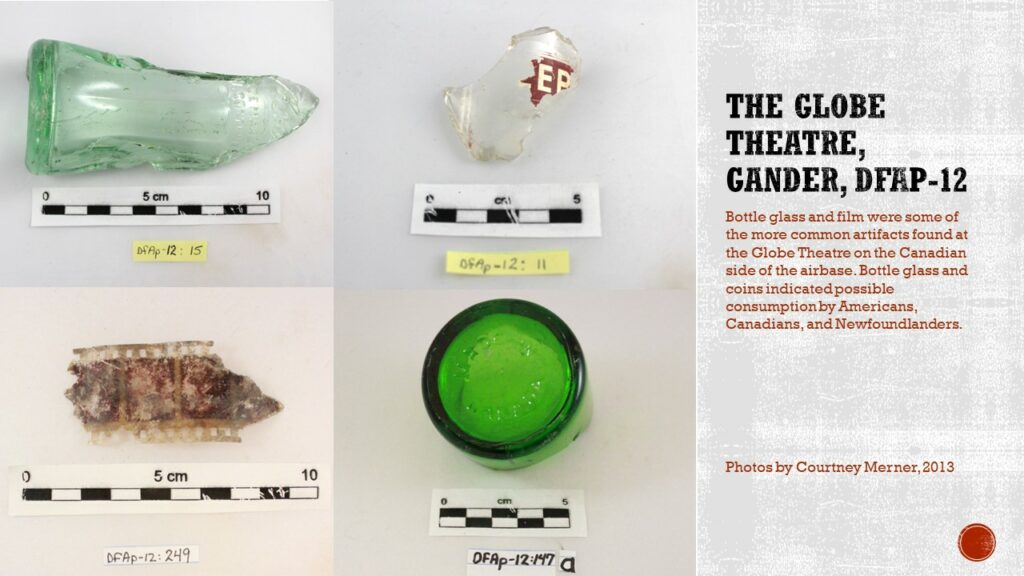

That brings us to the war era. Most of the archaeological work in the province is from this era. Of course, Mike Deal has done a great deal of work, and he’s the one who introduced me to the field. The archaeological work has focused on investigating airplane crash sites, but other work has been done, such as Mike’s work trying to locate historic aircraft in Gander, and my own excavations at the Globe Theatre, a theatre on the Canadian side of the Gander airbase. The Shipwreck Preservation Society of Newfoundland and Labrador has also been doing work in this field, including finding the location of the B-24 which crashed into Gander Lake in 1943.

The excavations at the Globe Theatre were interesting because it showed a snapshot of how the different countries on the base interacted and consumed. Some of the documents available, especially the American ones, make it sound like there was very little mixing between the four countries present at the Gander Airbase, Americans, Canadians, British, and of course, Newfoundlanders. The Canadian publications and the newspaper the Grand Falls Advisor do admit to more cultural mixing, with dances in Grand Falls being attended by servicemen from the US and Canada, and the Canadian magazine The Gander, sharing stories about sporting event where the countries played against each other. The archaeological record also saw some of that, with bottle glass and coins from Canada, the US, and Newfoundland found on site. Coca-Cola, in particular, was found on every American base, and for the same cost, during the Second World War. It wasn’t as common in Newfoundland before that, with Newfoundlanders generally drinking “beer” (brewed sodas) such as the Keep Kool line by Gaden. The Canadian impact isn’t as well seen, as some bottles for Newfoundland soda companies were bought from Canada, but numerous bottles did have Canadian makers marks. Newfoundland, American, and Canadian coins were also found on site, most of which were found near the front entrance to the Globe, so were likely coins dropped when paying admission to the theatre. Now, the timeline for the Globe is a little skewed, as it did remain open after the war period and after the military left, and continued to be used by the civilian population until the 1950s or 1960s when Gander moved from directly next to the airport to where it stands now.

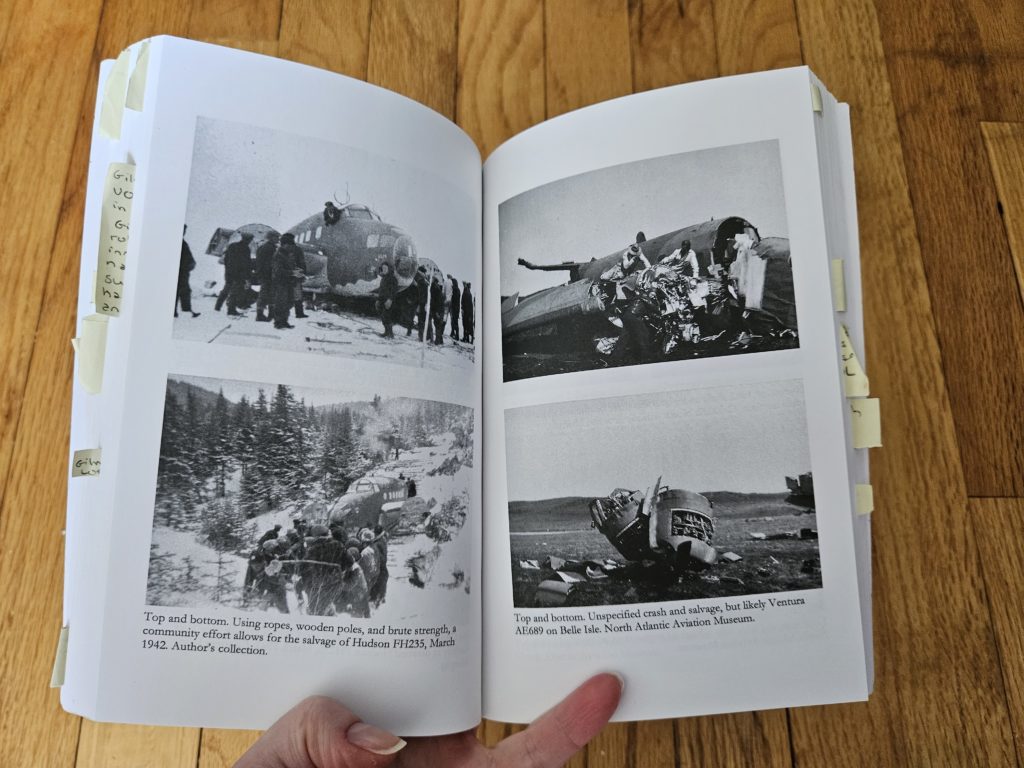

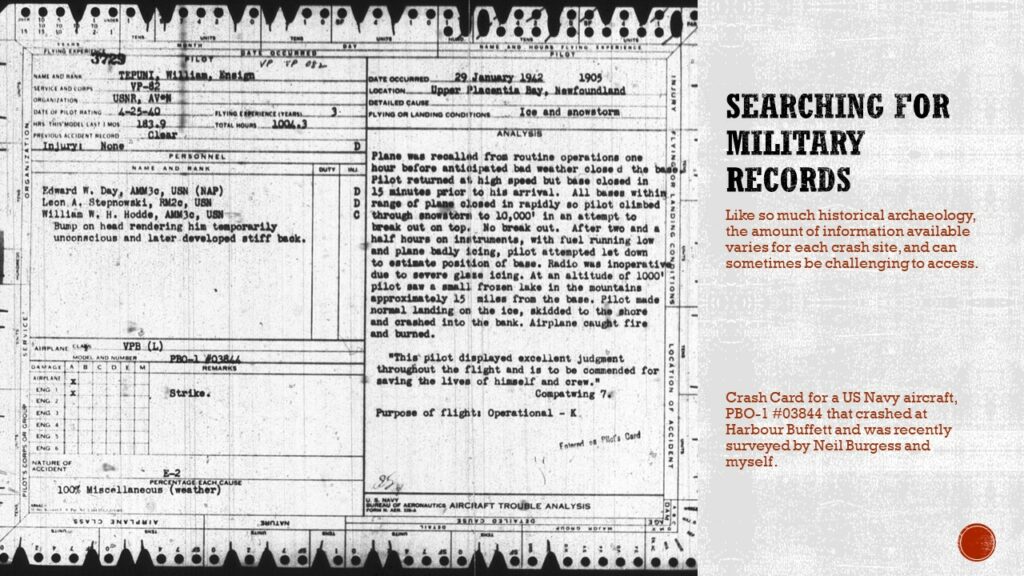

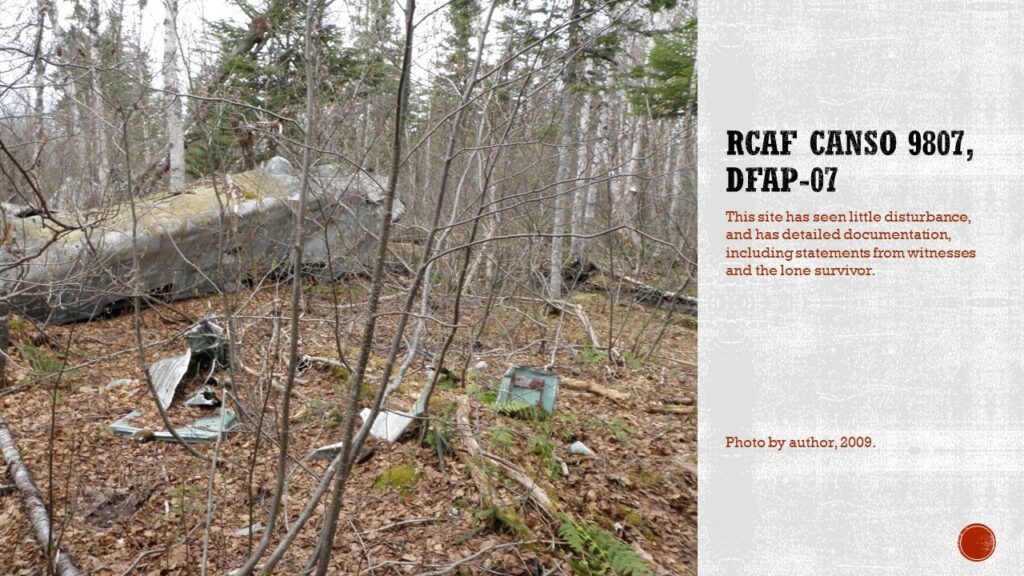

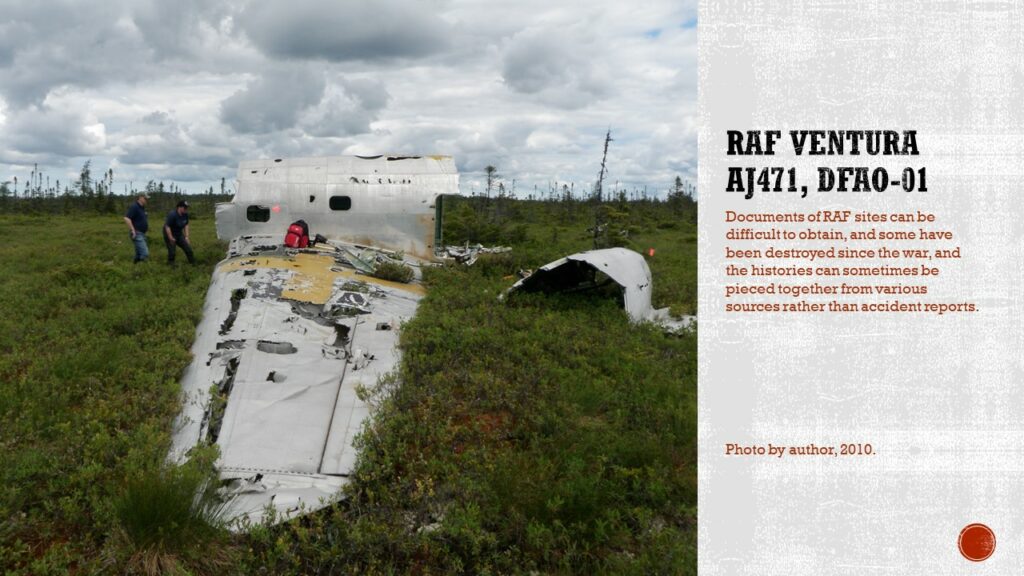

Plane crash sites can offer varying information. For the most part, there are detailed air crash or incident reports available, often containing witness statements and details about the accident. In other cases, there is no official report available, but information may be found in personnel files, though due to privacy restrictions, personnel files may only be available to the individual or immediate family members if the person survived the war. In particular, British and American files can be more challenging to access, while Canadian and Australian records for those who died in service can be accessed online. As well, the state of the material culture record can vary. Some sites are almost untouched, having been recovered by the miliary during the war and only visited infrequently after the war, while others have very little that remains, having had almost everything, especially any recyclable material, removed from the site.

The information that can come from crash sites does differ based on what is available. For instance, a relatively intact site with significant detailed documentation can confirm or refute some of the witness statements. An intact site can also give some indications about the crash mechanics, though nothing as detailed as a crash investigation is typically possible because generally key parts of the aircraft would have been removed during the initial crash investigation/recovery, such as instruments, engines, and any other sensitive equipment.

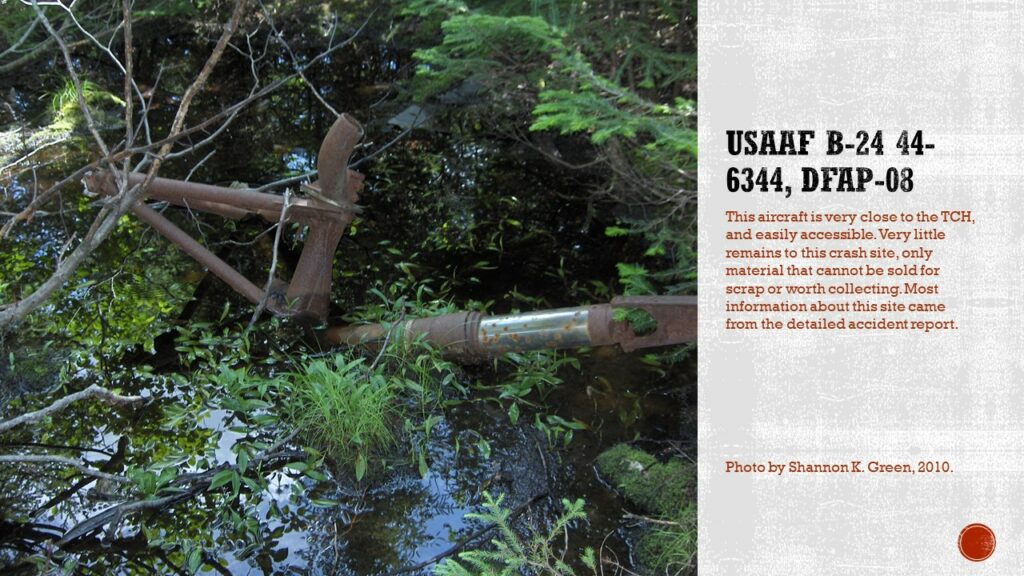

In other cases, a site may have a lot of documentation, but very little material culture. This is common for sites that are easily accessible, often near roads, where large amount of material can be easily removed. The archaeology often gives more information about site use and reuse rather than anything relating to the crash itself. Using the detailed documentation, especially if there are photographs available, and sharing them with the public, can help communities protect sites. Having visuals that show just how much a site has changed can sometimes create a greater sense of stewardship with local historical organizations and museums, who, in some cases, will take it upon themselves to help protect all sites, both those with little material culture and those relatively intact.

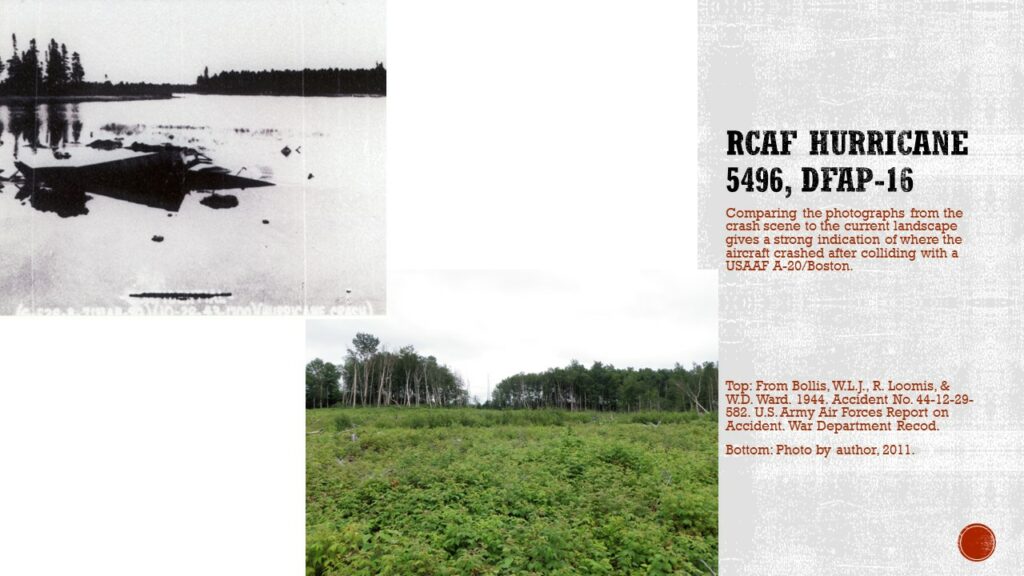

In one case, the detailed documentation allowed for archaeologists to locate where an aircraft had crashed based on the incident report photos and comparing them to the current landscape. The aircraft had been recovered during the war, and the pond it had crashed in drained when the runways was being extended after the war. No material culture could be found, but using the photographs and local informants gave enough information to theorize where the aircraft had crashed.

Some sites have very little documentation, but more material culture. Generally, because modern war history has such an active group of professional and amateur historians, some information can usually be found, though it is fragmentary and, depending on the source, not always accurate. The material culture of the site might be able to offer more information, such as if the crash was high or low energy, based on the amount of damage, as well as help positively identify the aircraft.

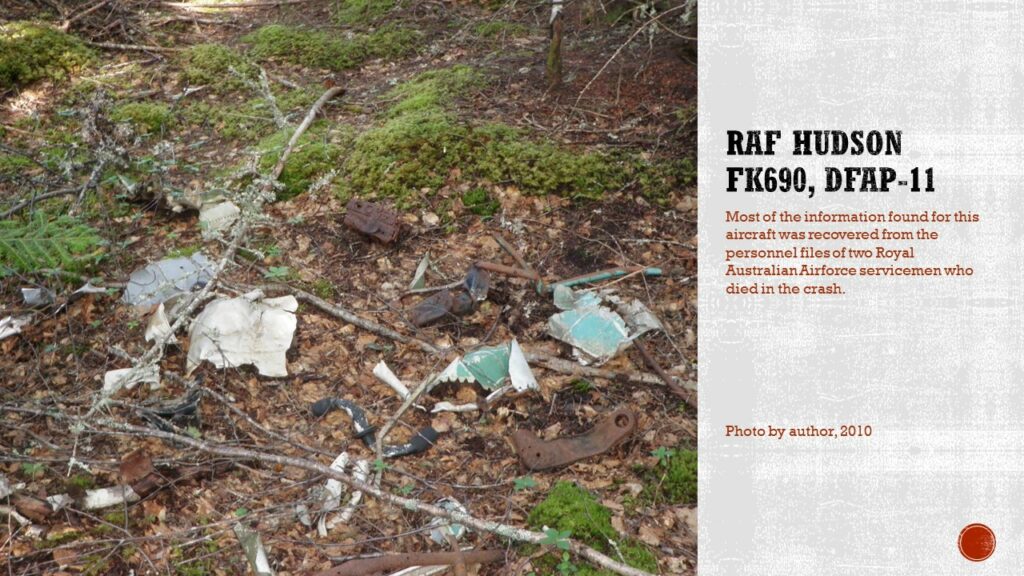

Finally, there are a few unfortunate sites with very little material culture and very little documentation. Sometimes, in these cases, some creativity might be involved to trace the history of the crash, such as searching for the personnel files for the victims of the crash, and using local stories to try to piece together the story.

Second World War aviation sites are all over our province, and they are generally at risk to scrappers and collectors. Conducting archaeological investigations and giving these sites statues as archaeological sites does help protect them to a certain extent. What may help even more is sharing the information garnered, whether accident reports or current pictures of the sites, with communities and community organizations. There is a general appreciation for the research (not always, but most of the time) and the information sharing, which leads to greater community involvement and protection for the sites. In some cases, like the Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest in Gander, site inventories can be used by the organization to help monitor disturbances to the sites on their land.

While talking about the information available around Second World War sites, it is not always easily accessible. Some reports were acquired through interlibrary loan (I’m not even sure if I can access that anymore) or had a cost to acquire through archive organizations. For many of my reports about United States incidents, I paid an individual who has made a business of copying microfilm available only in-person, and selling the incident reports, though at this point we’ve hit more of a barter situation where we share information, which is nice for my bank account. It’s not always easy to locate the material, so there are those who were involved in some of these accidents who do not know how to find the information. Over the years, I have been in contact with many people, from family members who lost someone in a crash, or servicemen who went on missions to crash sites without knowing the story of the event. Being able to provide any information can sometimes create a level of closure for questions that have gone unanswered for over 75 years. Even if I have a detailed report, there is a strong chance that those getting in touch with me have not been able to find such documents themselves, and I am always happy to share the information I have, when I can.

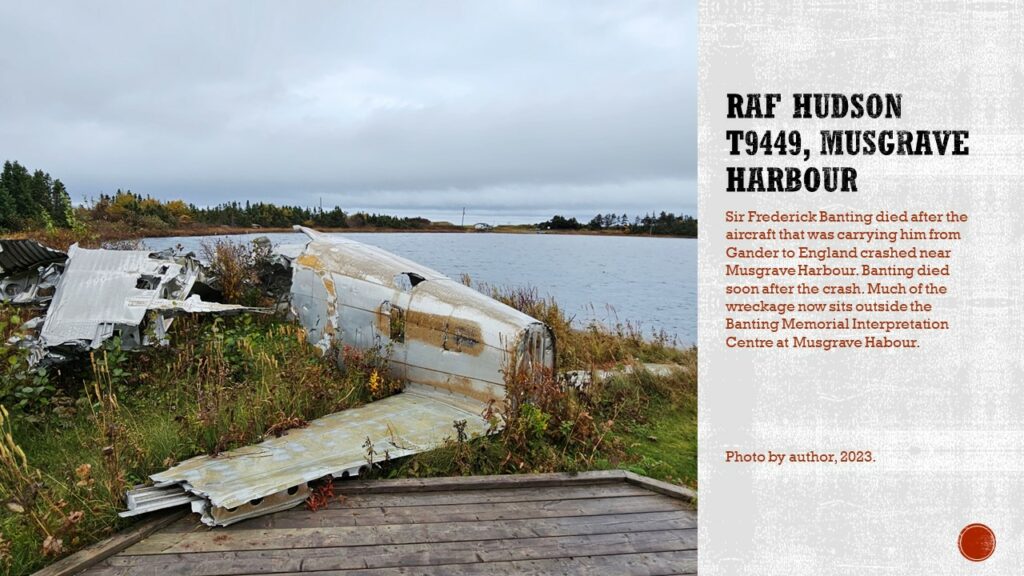

The archaeological work doesn’t end after the Second World War, but the nature of the crashes and the information available changes. During the war, many of the crashes and incidents were not reported on in the media, some exceptions, of course, and, from a Newfoundland perspective, after the crash of Sir Frederick Banting’s Hudson in 1941, most of the documentation is internal. The first crash at Gander, which had no fatalities, has a report in The Rooms, and there is a significant file on the crash, rescue, and recovery of Banting’s crash. That one also made international headlines. A big part of that was the celebrity of Sir Banting as a co-discoverer of insulin. But after that, the media would often only report on incidents that impacted communities that they were allowed to report on. Even then, that information was often limited.

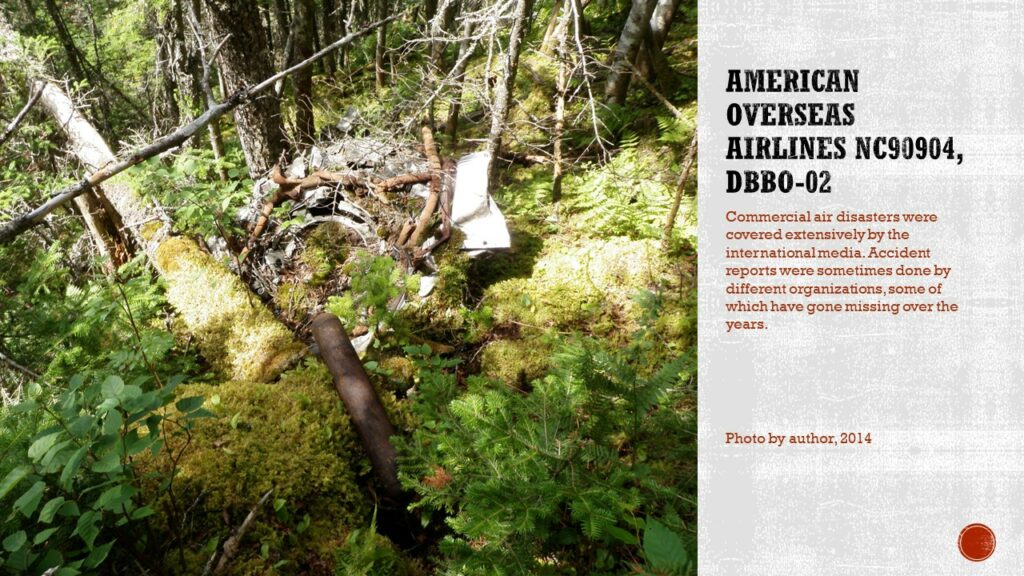

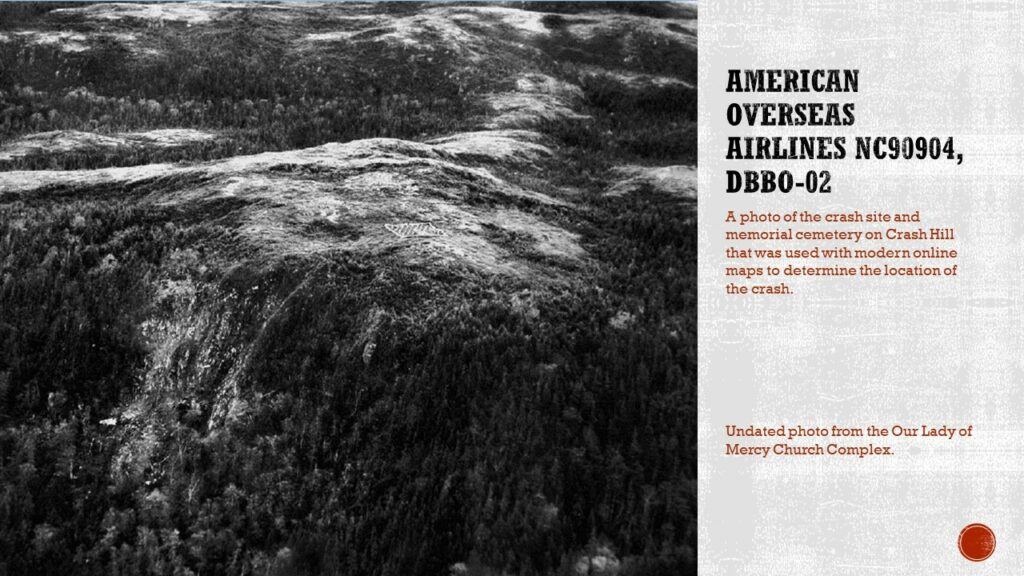

After the war, the information on aircraft incidents changes again as the secrecy was no longer as important and the media could report on events surrounding commercial flights. In particular, the media followed the crash of the Sabena near Gander in September 1946 and the subsequent helicopter rescue (first one on the island), and two weeks later, the crash of an American Overseas Airlines commercial flight outside of Stephenville. There are also documents relating to both crashes in the Rooms, though the internal documents for American Overseas Airlines seem to have gone missing as the airline changed ownership and its name multiple times since 1946. As well, relying on media information can have its own challenges, as misinformation can spread as stories about the accidents are told, or even just trying to confirm a passenger list, as I recently discovered trying to list all the passengers and their occupations or reasons for trying to fly to Berlin. Names can be misspelled between documents, and information can vary between news sources.

On the other hand, post-war military crashes will sometimes be covered in the media, such as the crash of the B-36 near Burgoyne’s Cove, but often not with the same level of coverage or as much speculation as seen in the commercial crashes. Not to say that there isn’t speculation about these incidents, because there are almost always theories and conspiracies surrounding a crash site, regardless of if it is military or commercial. But that’s another topic for another time.

Often, there is very little follow up on any of these sites. Once the crash investigation is over, little is often done with a site. They can sometimes be visited by those in the woods, whether hunting or trapping, or just hiking. The deeper in the wilderness, the less likely they are to be visited. In some cases, such as the 1946 AOA crash, the site can be “lost”. There were aerial photos, and it was known that it had crashed on Crash Hill, formerly Hare Hill, but not exactly where. An archaeological investigation used images from the time and Google Earth images to determine exactly where the site was, and I was guided there by a local outdoorsman who had never seen the site even though he had hiked the area many times. Finding the site, I could assess the state of the site, and through documentary research, share that the cemetery at the top of the hill did not contain the bodies of the victims, though the mass graves reported to be on site were not located on the brief site visit. Three family members of the victims have reached out to me and I have shared information, one even visited Newfoundland on a cruise ship, and a member of the Stephenville Regional History Museum picked them up from Corner Brook, took them to Stephenville, and showed them around, though not to the crash site as it is difficult to access.

Finally, I have worked on more recent aviation sites. Using the same techniques to record sites old enough to be considered archaeological, at the request of the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s, I recorded a 1978 crash on some farmland in the community. The work was done in advance of the 40th anniversary of the crash and both Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s and Torbay planned to try to do something in commemoration. I’m not sure, but it seems that the memorial is still in the works. All on board were killed in the crash, including the then-mayor of Torbay. The town is now using the site inventory to monitor the remains of the wreckage. The investigation also allowed some of the myths and stories around the site to be dispelled, including a statement from the owner of the airline, who said the pilot tried to turn back to the Torbay Airport when it crashed, though this is not indicated in the crash investigation, which says the cause was poor weather, and confirmed that the aircraft was facing away from the airport when it crashed, likely hitting the hill in a thick fog.

Overall, aviation archaeology is still trying to standardized methods, and practitioners discuss the theoretic approaches to interpretation in an attempt to separate aviation archaeology. Recently, a group of North American archaeologists, including myself, published a textbook called Strides Towards Standard Methodologies in Aeronautical Archaeology. This is inspiring a group in Australia who do an international conference called Aviation Cultures to bring together a selection of aviation archaeologists from around the world to write another book from that broader perspective.

Aviation archaeology is still a relatively new field, and still has a lot of growing and learning. It will take a lot of time to shake off the title of wreck chasers, especially when there are still a lot of people out in the world drawing conclusions to fit the story they want to tell and who are making a lot of money doing that. The aviation archaeology community is still small, and the types of work vary, from excavating war-era camps, bases, and other infrastructure, to finding, recording, and researching aircraft wreck sites to preserve and memorialize the sites. A great deal of work is underwater work, with limited work being done on terrestrial crash sites. But overall, the field is growing and figuring out how to define it as a legitimate branch of modern archaeology.