This was my first post on my first blog, posted on 19 May 2013. It is also perhaps the most contentious post. In the aviation community, it seems that Filotas causes a large divide, with passionate opinions on either side. I am not an aircraft incident investigator, but an archaeologist trying to figure out how to record and preserve old aviation material culture and share aviation history. I have been criticized for not knowing as much about aviation as others, but I came late into this aviation game and try to surround myself with experts who have taught me a great deal and will continue to teach me as we work together.

That said, my perspective on Arrow Air 1285 is coloured by being a Newfoundlander. It was the first crash site I ever visited. I have vague memories of being at the site as a young child because my great uncle wanted to visit it and we were driving through Gander on our way to Stephenville. I know it was before 1988 because my brother was not yet born. I remember the area being strangely silent (anywhere with trees in Newfoundland is typically full of birdsong) and the scar from the aircraft still being new. It was before the memorial was erected and the area tidied up. As I say below, I was only 4 or 5 years old, but the memory stuck with me. I also know that Gander is an airport town and especially in 1985 while Gander was still the “Crossroads of the World”, almost everyone knew aviation. This isn’t like many places where the airport is important to the town, in Gander, the airport is the reason for the town and almost everyone has some connection to the airport. In fact, it is still very common to see people hanging out at the end of some of the runways to watch the planes. As well, the way the highway is situated in relation to the airport, the aircraft are so low you can almost reach up and touch them (or so it feels) so I hold the witness testimony in high regard. But again, that’s the archaeologist/anthropologist in me. It’s the same way that I will listen and give credit to all of the conflicting stories about the Sabena diamonds.

Watching planes take off from the Gander Airport. Photo by author 2010.

This perspective has also caused divide between myself and some of my colleagues. I have one in particular where we have agreed to disagree because as an investigator it is unwise to rely to heavily on witness testimony and given the weather, it’s most likely ice on the wings. I also work as a tour guide, and had one gentleman say to me on my tour that he was an accident investigator (he didn’t say with what organization) and completely believed that Arrow Air 1285 had to be ice on the wings. Then they visited the crash site as part of his cross-Newfoundland tour. He doesn’t believe it is ice on the wings anymore.

Plus, we Newfoundlanders know about ice and snow.

But, this is a review of Filotas’ book. Believe his perspective or not is up to you. I am not trying to sway anyone, just writing a review. On to the original post….

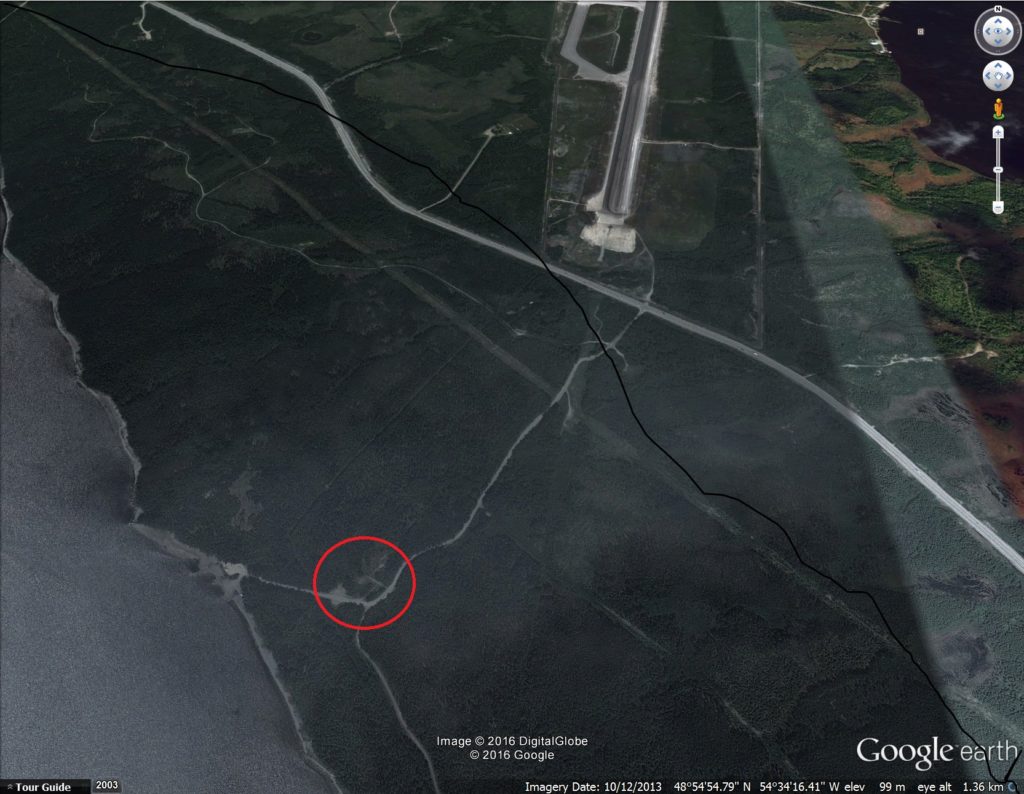

The location of the crash site (circled) in relation to the end of the runway and the Trans Canada Highway that passes through Gander. From GoogleEarth.

The Silent Witness Memorial off the Trans-Canada Highway in Gander, NL, is a haunting site. Between the end of runway 22 and Gander Lake, just a short distance from the highway, is a clearing of land and a monument of a soldier holding hands with a little girl and boy. The site is powerful, even without knowing what happened there. I remember visiting the site when I was young, maybe only 4 or 5 years old. I couldn’t remember much else about that drive beyond driving by the airport at one point, but I remember going to the Silent Witness site. I remember no statue, just a clearing with a few small trees. The scars were still visible from the incident.

The original memorial made from pieces of the aircraft. Photo by author 2009.

On 12 December 1985, a chartered Arrow Air flight, bringing home members of the 101st Airborn Division from a peacekeeping mission, crashed, killing all 256 Americans on board. The flight was leaving Gander Airport after a refueling stop. The DC-8 left the runway, barely cleared the highway, and landed in a devastating, fragmented and flaming wreck, killing all on board. The cause of the wreck has never been determined.

This is where Les Filotas’ book, Improbable Cause: Deceit and Dissent in the Investigation of America’s Worst Military Air Disaster is of interest. The official explanation for the crash is ice on the wings, but workers at Gander Airport deny any ice on the aircraft and witnesses will still talk about how the aircraft was on fire as it passed over the highway – before it crashed. The energy of the crash, and the fact that the aircraft virtually disintegrated, points to something much more severe than ice on the wings, but no one would investigate other theories.

Filotas was on the board of the Canadian Aviation Safety Board (CASB), a short-lived division of Transport Canada charged with investigating aircraft crashes. In his book, Filotas recounts the investigation of the crash, with detailed background research and verbatim discussions that occurred once he was on the board. The book is well researched, with detailed citations throughout. He keeps the crash within the perspective of aviation disasters worldwide, framing the background of the CASB through Canadian aviation incidents and the Board’s creation to the work they did before, during and after the Arrow Air disaster. He also maintains a worldwide perspective, looking at how international incidents shaped, or didn’t shape, the conclusions reached by the board.

Overlooking the memorial and Gander Lake. Photo by author 2009.

I wouldn’t consider myself to be a conspiracy theorist, but this book really makes me wonder. Filotas uses parallels between the investigations into the Hindenburg disaster and Arrow Air to introduce and conclude his book, and frequently brings up in board meetings the idea that politics are what’s leading investigators to push the idea of ice on the wings and to completely discount other theories, such as sabotage. While Improbable Cause does not confirm that sabotage was the cause of the crash, Filotas discusses how a minority of the board, who produced a minority report, did not believe that ice on the wings caused the crash and put forward alternate ideas, such as the evidence for an explosion in the cargo hold. He looks at the difficulties the minority had in getting any questions answered, obtaining documents, or being allowed to talk to experts who were not chosen by the chairman on the board. Filotas also details such attitudes that I, and by his tone, he, found disgusting, such as the idea that the family members of the deceased were not persons of interest in the view of the board and so were not privy to drafts of the report or information after the reports were released.

The impact site of the aircraft. Source.

While I knew that the official cause of the crash was ice on the wings, even though residents of Gander saw the aircraft pass over the highway already on fire, I did not know the level of conspiracy associated with the crash. Reading the account, it is amazing what the board denied and refused to question, such as the unknown crates that were loaded on the aircraft in Cairo or the two passengers listed on the original manifest but who were missing from the site, or the evidence for fire on board the plane prior to impact. The fact that the board would state that passengers who showed high levels of cyanide in their blood must have lived for a few minutes on site, and might have survived had Gander firefighters not taken 7 minutes to get there, must have been difficult for families and rescue services. But admitting that there might have been a fire on board the aircraft before it crashed would not have agreed with the ice on the wings theory. In particular, I found the last chapter fascinating. I knew there would be no answers, but reading about the inquiry done in the United States I hoped there would be, until the inquiry seemed to stop asking difficult questions and had a conclusion prepared before all the witnesses could be interviewed.

The Silent Witness Memorial statue. Photo by author 2009.

The Silent Witness site is powerful and haunting. I have been to a number of plane crashes at this point, some where there have been fatalities, but none of them feel the same way that this one does. If you pass through Gander, pull in to the site and take a moment to remember the 256 victims. Maybe someday it will be known why they died.

[Author’s note: This post did garner some chatter, and a correction. I feel it is best to include these comments in the repost, even if I don’t come off in the best light, and they correct some of my errors and misunderstandings in the original post]

bdff5b4c-e151-11e3-9758-274ab4c14d6321 May 2014 at 18:38

Good review. I need to correct that CASB was not a division of Transport Canada… rather it was the new independent aviation safety board created in 1984. It was further reorganized in 89 as a new multi-modal Transportation Safety Board (TSB), and it has been this way to this day. At the end of the day neither the ice theory or the bomb theory could ever be proven, so the real cause is “undetermined – but a lot of opinionated armchair experts have lots of suggestions…”. I side with Filotas and the conspiracy theory, but who really knows.

ReplyDelete

E1craZ4life24 September 2014 at 09:42

This has got to be the most poorly constructed argument I have ever seen. There really isn’t anything in the book that isn’t contradicted by other arguments within said book, can’t be explained as having been a consequence of ground impact rather than a cause of the crash, and/or is relevant to the accident itself. The official conclusion was iced wings in addition to underestimated weight, and the minority report does a poor job of refuting the evidence in the other report.

ReplyDelete

Lisa Daly2 October 2014 at 12:25

Thank you for your correction bdff. I must have misunderstood that part in his book. I’ll be honest, that first bit about the history of CASB, TC and TSB was a little confusing for me. I will have to read the book again to try to clarify it all in my own mind. E1, thank you for your comment. I’m not entirely sure if you’re arguing my review of the book or Filotas’ argument. I am not an aircraft incident investigator, and my interest is much more in the history and social history of aircraft and aircrashes. In that respect, I find this site fascinating because there is so much social history around it as well. I have heard so many people in Gander talk about this site, and a few of them talk about seeing the actual aircraft as it crossed the highway. Their stories are powerful and does make a person wonder about what really happened with the aircraft. As well, Gander has rarely ever had problems with ice on the wings; they know that weather and have had a good record of deicing since WWII. Of everything, it’s what bothers me the most about the official conclusion. Yes, ice buildup was noticed over an hour later on a different aircraft, but in Gander, that hour can mean completely different weather. For instance, some of the WWII era crashes I have researched happened because the weather changed so rapidly that by the time an aircraft returned from escorting convoys, the weather in Gander was completely different. But, it is something that no one will ever really know. For now, thank you for your opinion and I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

E1craZ4life14 October 2014 at 09:28

I was talking about Filotas’s arguments. I’ve studied a large number of plane crashes, and I have ambitions of becoming a pilot. I can’t say that anything Filotas says makes sense and/or can be verified as being what could happen if there really was an in-flight explosion, which I doubt. And somehow, I feel that the mere authoring of the minority report has led people to believe the accident is an unsolved mystery, when it can be easily seen that iced wings and excess weight together can cause an accident. And the more I studied other crashes, the less credible the minority report was to me.

Lisa Daly21 January 2015 at 18:14

That’s fair. Sorry if I was defensive. I am not a crash investigator, but I have been to this crash site and it is one that strikes me as odd, mostly because Gander has such a good record for icing and winter flying. I haven’t read many post-war crash investigations, and the war era ones were often rushed. I thank you for your comments, I would like to learn more about this crash because there are still questions that surround it, whether they are just conspiracy theories or not.