My originally scheduled post was supposed to be a review of A Gentlemen’s Agreement: Newfoundland and the Struggle for Transatlantic Air Supremacy by Robert C. Stone, but I still have half of the book to read. I figured it would be unfair to quickly read the remainder of the book just for a blog review, so instead I am posting the next scheduled post instead. This was first adapted from my own thesis, then a version of it posted on the Gander Airport Historical Society page under their Warbird Down section. So, while you may not know my planned schedule, I really am trying my best to stick to it this year to bring you new content every second week.

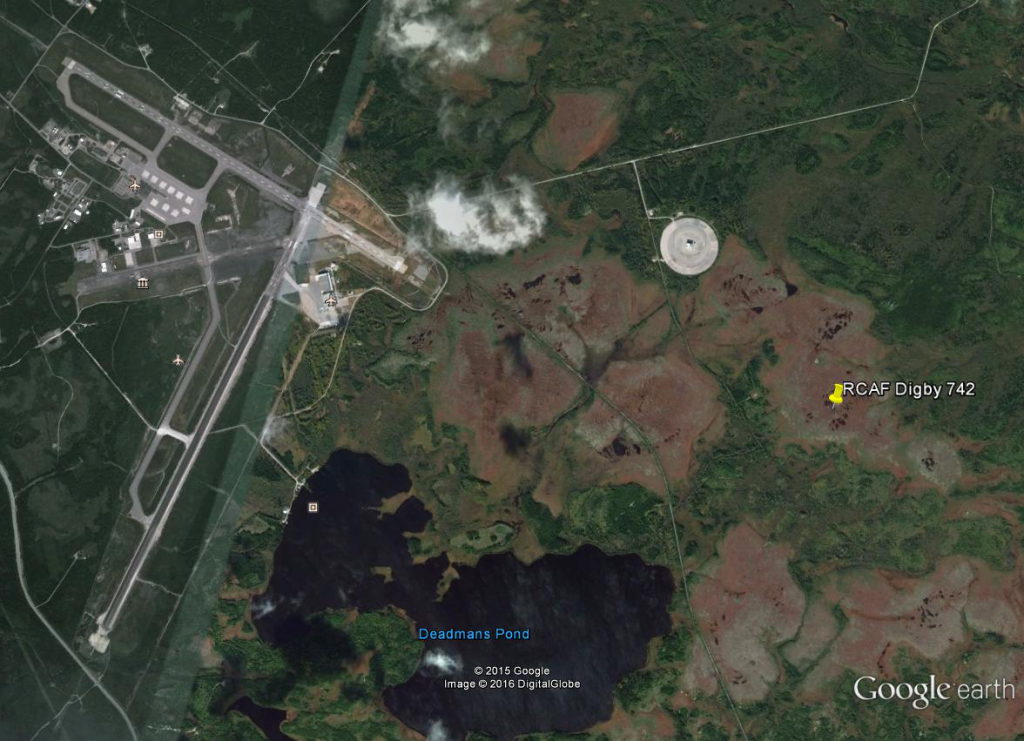

On to explore RCAF Digby 742, crashed at Gander. For video of this site, please see my Land and Sea episode “Fallen War Birds“.

Measuring the debris field. Photo by author, 2010.

Perhaps the most notable thing about this site is how little it has changed since the crash.

Some of the Digby that remains on the site. Note the similarity to the picture below. Photo by author, 2014.

Image of the RCAF Digby wreckage taken during the crash investigation. Note the similarity in the site picture from 2014 (above). From Heakes 1941.

At 1856 GMT on 24 July 1941, RCAF Douglas Digby 742 left Gander with a crew of six for the purpose of convoy patrols. At 2320 GMT the weather began to deteriorate and the Meteorological Office predicted that the ceiling would remain at about 1500 feet with showers. At 2326 GMT the aircraft was recalled, but Digby 742 did not immediately respond. The recall notice was repeated four times by Gander Station and twice by RCAF Station, Sydney. The recall was acknowledged at 0030 GMT and at 0151 GMT the aircraft was in range of the Gander airbase. Digby 742 was spotted by Airport Control, but the aircraft reported that it could not see the airport. By this time, the ceiling had deteriorated to 200 feet with rain and increased wind and the cloud had begun to blow across the runway. When Digby 742 arrived, RCAF Digby 756 was attempting to land at Gander and Digby 742 was instructed to circle until Digby 756 had landed. Digby 756 landed safely at 0219 GMT but for approximately the next twenty minutes, Digby 742 was out of communication range. Captain Tomsett was instructed to proceed to Dartmouth where the weather conditions were more favourable but the Captain stated that he would attempt to land at Gander one final time and would proceed to Dartmouth if that landing was unsuccessful. At 0310 GMT a loud explosion was heard and there was no further communication with the aircraft. At 0330 GMT, the ceiling began to steadily rise becoming 1400 feet by 0530 GMT (Heakes 1941).

| Name | Rank | Serial Number | Unit | Duty | Injuries |

| Tomsett, M.E. | F/Lt. | C.1069 | 10 (BR) | Pilot | Fatally |

| Mather, W.H. | P/O | J.3479 | 10 (BR) | Pilot | Fatally |

| Pratt, A.G. | P/O | 10 (BR) | Navigator | Fatally | |

| Hunt, M.S. | Sgt. | R60720 | 10 (BR) | Air Gunner | Fatally |

| MacDavid, R.L. | Sgt. | R73032 | 10 (BR) | Air Gunner | Fatally |

| Crawford, T.J.E. | AC 1 | R65641 | 10 (BR) | Wireless | Fatally |

Crew list for RCAF Digby 742. Adapted from Heakes 1941

At first light, two aircraft were dispatched to search for Digby 742. The wreck was located almost immediately after take-off and a ground party which had been organized during the night was sent out to the scene of the accident. F/L MacLennan, Medical Officer at the RCAF Station Hospital, was in the ground party and assessed the injuries of the crew. The bodies were located throughout the site, and in some cases were thrown as far as 240 feet from the main wreckage. All of the crew except Sgt. MacDavid died instantly; MacDavid succumbed to his injuries shortly after the accident. All crew were found to have extensive injuries, and in all cases except for AC 1 Crawford, showed fractures to the skull and long bones. Crawford sustained massive trauma to the abdominal and thoracic areas, causing death. When the crew were examined they were all in a state of rigor mortis (Heakes 1941). As a result of this crash, it was believed that there would be further casualties in Gander, so an area was selected for the Commonwealth War Graves and these airmen were the first RCAF crew to be buried in Gander (Heakes 1941; Pattison 1941; Walker 2002).

Map of the debris field. Daly 2015.

The accident report gives the evidence that the aircraft came in too low and the starboard wing struck the bog, resulting in the crash. It states:

From the furrow out in the ground it appears that the starboard wing tip struck the ground after which the aircraft cartwheeled resulting in the wing, nose and engines being torn from the fuselage and the fuselage breaking in the centre behind the bomb-bay (Heakes 1941).

Where the wing struck the bog in 1941 is still visible. Note the debris in the scar. Photo by author, 2010.

The archaeological map of the site agrees with this assessment. The scar where the wing tip struck is still visible and does contain some aircraft debris. The artifacts in the scar could not be measured accurately to be placed on the map because while the whole area is unstable, the areas that were damaged in the crash are much too unstable to walk on. The wings are to the northwest of the impact point, and the tail is partially submerged to the east of the impact point. The cockpit was not visible and may have been destroyed by investigators or sank through the bog. One piece in an open area of water could not be measured in the field and was measured from GoogleEarth images. This piece, which looked like a section of engine cowling, is approximately 260 feet (75 meters) from the main area of wreckage: the tail and rear end of the fuselage. This could be approximately where the bodies of P/O Pratt and AC 1 Crawford were located as the witness statement states:

I was shown the body of P/O Pratt. The body was 240 feet from the main wreckage, body partly submerged in a small pond, face and head above water. […] I was shown the body of AC 1 Crawford, T.J. The body was 220 feet from the main mass wreckage and was attached to seat [sic]. It was found in the small pond with head submerged in water (Heakes 1941).

Approximate location of the wreckage. Google Earth.

The engines were in good condition prior to take-off and the aircraft had passed inspection. The altimeter settings had been passed on to the aircraft more than once, but Digby 742 never acknowledged receiving them. Salvage of the aircraft was requested, but given that the engines and bombs had sunk beneath the bog, Eastern Air Command in Halifax determined that the salvage values of the engines would not warrant the expenditure necessary to drain the bog to retrieve them. Similarly, due to the boggy nature of the area, it was believed that the six-hundred-pound live bombs from the aircraft would soon rust through to become inert and up to that point the area should be treated with caution. Until the bombs were determined to be inert, it would be unsafe to attempt salvage operations, especially of the engines (Heakes 1941).

Excerpt from the 1941 crash report discussing the viability of recovering the engines. From Heakes 1941.

Although weather conditions had deteriorated, at this time there were no regulations for minimum ceiling. The conditions that were present at the time of the crash were poor and landing should only have been attempted by an experience pilot. As a result of this crash, recommendations were made to the RCAF to put in place regulations for landing in poor conditions based on the time of day (day or night flying) and the experience of the pilot; an experienced pilot is considered to have completed at least 300 hours of flying on that specific type of aircraft. The determination that weather conditions are poor would be based on the ceiling level and at the discretion of the Aerodrome Control Officer (Heakes 1941).

Based on images taken after the initial accident compared to the site in 2010 and 2014, it looks as if the wreckage has been relatively untouched since the incident. The major change visible is a slow settling and sinking of the aircraft into the bog. As well, the different times of year will make the site look different depending on the amount of recent precipitation. As stated in the incident report, the heavier items, such as the engine and the bombs sank under the bog before investigators reached the site, so the assumption can be made that any other heavy pieces of the aircraft, especially those with a small surface area, sank as well. What does remain are essentially pieces of aluminum of varying sizes (from small fragments of a few inches to a large wing section) “floating” on the bog. This does leave the site relatively intact since the crash, and thus allows for a better idea of the crash mechanics (Young 2014). As seen above, the crash report was detailed regarding the mechanics of the crash, and looking at the site it is possible to see the site similarly to how it was seen in 1941. In this case, the incident report has been able to inform the researcher and point out other areas, such as the engine cowling in a nearby area of open water, where debris can be found. This makes this site one of the most intact in the Gander area that has so far been examined by archaeologists.

What remains of the wings, “floating” on the bog. Photo by author, 2010.

That said, there is evidence that people have visited the site. As is typical for known crash sites, a yellow X was painted on one of the larger pieces of wreckage. Names and dates of site visitors have been scratched into that paint. The majority of these names date between 1961 and 1968 and between 1983 and 1999. The Circularly Disposed Antenna Array (CDAA) was opened in 1970, which most likely prevented access to the site (RCAF 2009). According to staff at the facility, the antenna near the crash site was inactive in the 1980s and erected again in 2000, making the easiest access route to the crash site a restricted area (Fudge 2010). In fact, this researcher had to be escorted through the boundaries of the CDAA to gain access to the site. Because the site is still in operation, there is limited information about the area except that it is restricted.

Graffiti on the aircraft wreckage. Photo by author, 2010.

While this site can be accessed by other routes, it is not recommended as the site is unstable, especially near the debris and the scar from where the wing struck, and visitors are at risk due to the unstable nature of this bog (Hillier 2010). In fact, which investigating the site, even walking near a fragment of aircraft could cause it to shift on the landscape. As well, according to a bomb disposal expert with the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary, caution should still be taken on site until the time that the status of the bombs can be determined (Deacey 2011). The incident report believed that the bombs would be deactivated as they would rust through in the bog, but this may not be the case as bogs are environments that can actually preserve materials rather than destroy them.

Some of the Digby that remains on the site. Photo by author, 2014.

References

Daly, L.

2015 Aviation Archaeology of World War II Gander: An Examination of Military and Civilian Life at the Newfoundland Airport. Doctoral (PhD) thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Deacey, C. (RNC)

2012 Personal Communication

Fudge, M. (CAF)

2010 Personal Communication

Heakes, F.V.

1941 Douglas Digby Aircraft No. 742 Fatal Accident to Above at Newfoundland on 25-7-41. Department of National Defence – Canada RCAF, Gander, Newfoundland.

Hillier, D. (Newfoundland aviation historian)

2010 Personal Communication

RCAF (Royal Canadian Air Force)

2009 9 Wing Gander: History. http://www.rcaf-arc.forces.gc.ca/9w-9e/page-eng.asp?id=509 (accessed 28 Aug 2012).

Pattison, H.A.

1941 Letter to the Secretary for Public Works 10 February 1941. On file, Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador, GN Box S5-5-2.

Walker, R.W.R

2012 Canadian Military Aircraft Serial Numbers, http://www.ody.ca/~bwalker/index.htm (accessed 13 Sept 2012).

Young, D. (Aircraft maintenance engineer)

2014 Personal Communication