Royal Canadian Air Force Canso 9807 was requested to urgent operational duties, mainly convoy coverage. The aircraft departed in radio silence on 5 May 1943 at 0631 GMT from runway 15 and crashed a minute later, killing six of the seven crew on board (Table 1). Cpl. Urbain Edmond Antoine, who was located in the bunk compartment, was seriously injured, but survived the crash (Mulvihill 1943).

Table 1: Crew list for RCAF Canso 9807. Adapted from Library & Archives Canada and Mulvihill 1943.

| Name | Rank | Serial Number | Unit | Duty | Injuries |

| Casey, Brian Anthony | F/Lt. | C.1061 | 5 B.R. | 1st Pilot | Fatally |

| Barsalou, Joseph John | F/Lt. | C.1237 | 5 B.R. | 2nd Pilot | Fatally |

| Cleeland, James Rayson Wallace | F/O | J.11797 | 5 B.R. | Navigator | Fatally |

| Millar, James Herbert | P/O | J.20859 | 5 B.R. | W.O.A.G. | Fatally |

| Morrice, Alexander Frederick | W.O.2 | R.93368 | 10 B.R. | W.O.A.G. | Fatally |

| Stallwood, John Benjamin | Sgt. | R.122657 | 5 B.R. | 1st engineer | Fatally |

| Dube, Urbain Edmond Antoine | Cpl. | R.63059 | 5 B.R. | 2nd engineer | Seriously |

*There were a number of discrepancies between the incident report and the Library & Archives Canada records. The changes from the incident report are to add the first names where possible, J.P. Barsalou to J.J. Barsalou, Claeland to Cleeland, Miller to Millar, Morricee R.93362 to Morrice R.93368 and Cpl. Dube could not be found, indicating that he must not have died during the war. Dube was listed both as Urbain Edmond Antoine and W.E.A. within the incident report.

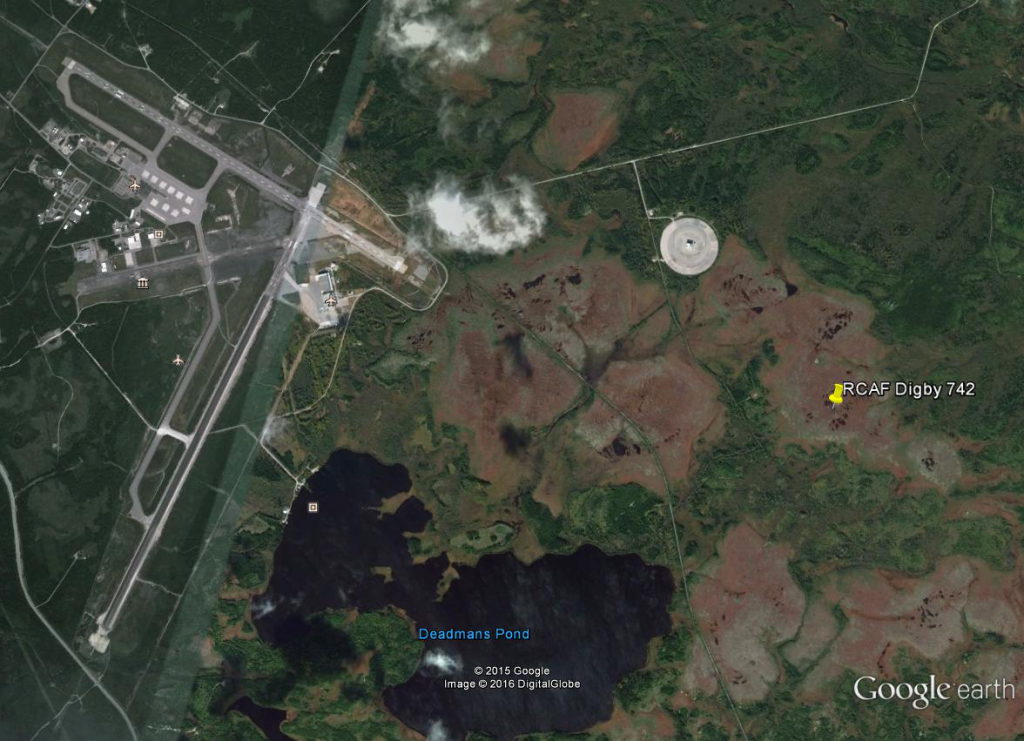

Prior to takeoff, on the evening of 4 May 1943, the Canso 9807 was inspected as part of the daily inspections. LAC Donald Harry Scott, R144305, signed off on the inspection work sheets. The aircraft was carrying a full load of gas (1,300 gallons) and of oil (80 gallons), and would have weighed approximately 33,150lbs. The maximum load for a Canso aircraft was 34,500 lbs., keeping the aircraft within the allowable weight. When Canso 9807 took off, the weather conditions consisted of fog coming in from the south with a ceiling of about 600ft but dropping rapidly. At a temperature of 31.5°F (about 0°C) there was the potential that ice could have formed in the carburetor, but not on the wings. But, according to the report, had ice formed in the carburetor the pilot would have noticed as he would not have been able to achieve takeoff speed with a full load. The aircraft took off without issue and flew over the American side before crashing (map 1). Witness reports vary from this point on. Some witnesses saw normal exhaust coming from the engines, but other witnesses reported the starboard exhaust flames going out, indicating the failure of that engine. Other witnesses saw both engines functioning, but said a whining noise indicated that the engines were using more power than normal prior to the crash. No witnesses reported any sputtering or backfiring of the engines, or other major indicators of engine trouble. The report concluded, based mainly on the witness testimony of Cpt. Dube and Captain George William John Gander, Commanding Officer of the 1st Aerodrome Defense Company C.A. (A) and the final witness to see the aircraft before the crash that both engines were functioning prior to the crash but were using more power than normal.

Map 1: Approximate location of the crash site relative to the airport. From GoogleEarth2016

According to the witness statement of Cpl. Dube, as part of the takeoff preparations, the pilot “ran up his engines in front of the hangar and then again at the end of the runway. Both times they sounded normal” (Mulvihill 1943). After a normal takeoff, Dube stated that the air was rough and once airborne, the flight was extremely rough. The aircraft began to climb, and then dropped suddenly. The aircraft leveled out again for a couple of seconds, then stated to fall once again. At this point, in his words, Cpl. Dube heard the crash and was thrown 40ft from the aircraft (figure 1). The final thing he could remember was a loud explosion which he believed was a depth charge. He regained consciousness later when in the hospital (Mulvihill 1943).

Figure 1: The tail of the aircraft where Cpl. Dube was located before the crash. Lisa M. Daly 2009.

The first priority for crash responders was to locate any survivors. Unfortunately, the crash was severe and due to the full fuel load, burned too hot to allow for anyone to approach the main area of the crash (map 2); the aircraft and surrounding trees were burning. Cpt. Dube was located and transported to the hospital. No crew members could be found outside of the main crash area.

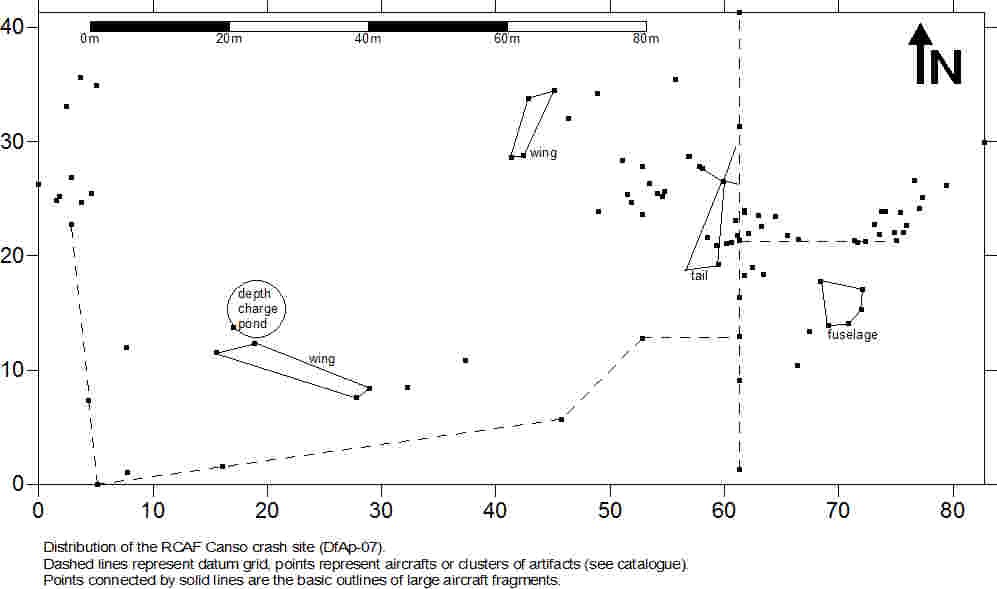

Map 2: The high energy crash scattered aircraft fragments over a significant area.

The crash was high energy and the aircraft was extensively damaged, so that no information could be collected from the instruments or controls to indicate the cause of the crash (Mulvihill 1943). The wings were damaged in that the port wing was relatively intact, but separated from the rest of the aircraft and the starboard wing was fragmented (figure 2). Due to the damage to the starboard wing and the relatively narrow swath created by the aircraft entering the forested area (only four feet wide), it was determined that the aircraft must have entered while on an almost vertical bank. The port wheel was found to be fully retracted in the wheel well, which would indicate that there was power to the starboard engine just prior to the crash (Mulvihill 1943). The rest of the damage is reported as follow:

Figure 2: Wing tip that has since been removed from the site by persons unknown. Lisa M. Daly 2009.

Hull

Broken in two main parts at the bulkhead between the blister and bunk compartments. The pilot’s compartment practically disintegrated while the navigator’s compartment was torn and twisted back over the engineer’s compartment (figure 3).

Figure 3: The hull, badly damaged. Lisa M. Daly 2010

Wing & tail section

The starboard wing was shattered and littered along the first seventy yards of the swatch. The port wing was relatively intact and lay one hundred and five yards down on the extreme right of the swath (figure 4). The tail was broken off and lay under the aft part of the hull (Mulvihill 1943).

Figure 4: The largest section of wing. Lisa M. Daly 2009

The report concludes that Canso 9807 crashed because it “stalled due to climbing at a critical angle in rough air” (Mulvihill 1943). The weight of the aircraft may have been a factor, as it was the second incident with a Canso under similar conditions. Therefore, it was recommended that the maximum weight of the aircraft be reduced to prevent further accidents.

This is a very concentrated crash site. Based on both archaeological and documentary evidence, this was a sudden crash and burned quickly. There is very little evidence of fire on the aircraft remains, such as melted metal, but site investigators reported that at first the crash was too hot to approach to located crew members. This does illustrate that fire and explosion are not always obvious in the archaeological record; the evidence of fire in this case being that the area is populated with birch trees rather than the more common spruce trees (figure 5). That said, the area of highest artifact concentration, which was most likely where the fire concentrated, is rather wet, with part of the fuselage being partially submerged. This could be hiding evidence of fire, or helped to keep the fire slightly more contained.

Figure 5: Area of high artifact concentration around the hull sections. Lisa M. Daly 2009

The site shows that the wing separated from the remainder of the aircraft first, followed by the tail, the front of the fuselage was at the furthest point from the runway. The cockpit was not located, but the report indicates that it was destroyed and the fuselage section could not be fully analysed due to it being partially submerged. As indicated by the site and the report, the wing broke in a number of places and scattered around the site. A wing tip was on the site in 2009, and photographed by archaeologists, but in 2010 this piece was missing from the site (figure 2). In 2011 the site was visited again to try to find this piece, without success. The tail is still in relatively good condition, and one of the blisters from the aircraft is still intact and in the possession of a Glenwood resident. The engines, tires and propellers are visible in pictures of the site taken at the time of the crash, but these were not found, indicating that they were removed by recovery crews during the war era (most likely) or by site visitors in subsequent years. I believe that they were removed at the time of the investigation due to the site’s proximity to the airbase, making it easy for the removal of all sensitive material but leaving the shell of the aircraft at the site. The interest in the starboard engine for the crash investigation would certainly suggest that the extra effort be made to recover that part of the aircraft (figure 6). The amount of aluminum remaining on site would also indicate this.

Figure 6: Images of the hull from the original crash report (Mulvihill 1943). Note changes to site in figures 3 and 5.

An interesting feature on this site is a small, round pond near the wings. In the report, USAAF servicemen who were helping with the rescue (at this point waiting for the fires to die down) were surprised, but not hurt, when one of the depth charges exploded about a half hour after the crash (figure 7). Cpl. Dube also noted that he heard an explosion which he believed to be a depth charge (Mulvihill 1943). This was most likely due to the heat of the fire. The hole created by this explosion is now filled with water due to the wet nature of the site, and now sits as a stagnant pond on the site. The depth of the pond was not established, but the diameter was so that it could be placed on the site map (Map 1).

Figure 7: The hole created by the depth charge exploding. Lisa M. Daly 2009.

The archaeological investigation does not add much information to the detailed report, but instead confirms much of what is stated, and provides an inventory of what is on site. It also shows changes to the site. I visited the site in 2009, 2010 and 2011, and because of Hurricane Igor in October 2010, the site had changed a little. Uprooted trees revealed more pieces of aircraft which were then added to the archaeological inventory and map (figures 8 and 9). Extreme weather can move objects as large as aircraft fragments, shifting them around the site as informants have indicated with the Burgoyne’s Cove B-36, covering them in debris as Hurricane Igor did to some objects on the Dolan B-24 near Gander, or uncovering them as seen with this site.

Figure 8 and 9: Changes to the site caused by Hurricane Igor. Top, uprooted trees; bottom, what the lifted roots uncovered. Lisa M. Daly 2011.

It is obvious from the missing wing tip that the site is threatened. The wing tip (figure 2) is obviously a very interesting piece, and could be of use to historical groups of the museum, but under provincial law, should be collected and catalogued by an archaeologist so that the province has a record of what historical material is available. The Rooms gladly work with museums to help them display artifacts, and also offer help when it comes to storing and conserving pieces.

Sources

Library & Archives Canada (LAC)

2016 Service Files of the Second World War – War Dead 1939-1947. Accessed 09 July 2016: http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/second-world-war/second-world-war-dead-1939-1947/Pages/search.aspx

Mulvihill, J.C.

1943 Proceedings of Court of Inquiry or Investigation Flying Accidents: Canso “A” #9807, Royal Canadian Air Force, Gander.

For an explanation of RCAF serial numbers, please visit: http://www.rafcommands.com/forum/showthread.php?6411-RCAF-Service-Numbers