Originally posted 05 June 2013.

Yes, another book review, but I am working on something much more interesting (although it would be nice if these posts generated some interest for these books). I’ve been going through a partial crash report for USAF 51-13721 an RB-36H which crashed in Burgoyne’s Cove/Nut Cove, near Clarenville, in 1953. There is still a lot of interest in this crash and I am just wondering how to best present it. As I said, I have a partial accident report to work with. The full report is available from AAIR, but I currently don’t have the budget for a $185 USD report. I’m also trying to get my hands on a copy of Under the Radar: A Newfoundland Disaster, which I think will involve a visit to my local library. Plus there are a number of websites who have done quite a bit of research on this crash, so I may have to break this up into multiple posts. And finally I plan to visit the site, and write up a final report after that. I have visited the site before, but seem to have lost all of my pictures on an old hard drive. Anyway, eventually I will figure out the best way to post the information, and to keep it in small, readable segments.

On to the repost from 2013…

I was given a copy of this book by a friend. His father died when flying into Gander, NL, on 14 February 1945. While I have helped with the archaeological research done on this site (DgAo-01, sometimes called The Eagle Crash, sometimes The Dolan Crash), most of the documents that I, as an archaeologist, had were military reports. Bill managed to find some interesting information about his father through this book and author.

Wreckage from DgAo-01, the Dolan or Eagle Site, in Gander.

Camp Rimini and Beyond: WWII Memoirs by David W. Armstrong, Jr. is a memoir of Armstrong’s war service overseas. As an American, serving in Newfoundland was considered to be overseas. Armstrong was first stationed at Camp Rimini War Dog Reception and Training Centre as a sled dog trainer, then stationed at Search and Rescue units in Newfoundland for two years during the war. His memoir talks about his time both in Rimini and Newfoundland, and discusses the more everyday aspects to Search and Rescue using sled dogs.

This book was interesting for a number of reasons. First, I am always looking to find more information about Newfoundland during the war era and Newfoundland history in general, and this book provides an outsiders experience. Most of his interactions are with the American and Canadian forces serving in Newfoundland, but he does often encounter Newfoundlanders, whom he refers to as Natives, in his travels. In two different stories, Armstrong talks about Newfoundlanders and lobster, first buying lobster for cheap, and the second about locals who were showing off a giant lobster claw.

I can relate. I stayed in Belburns for a night last summer and my hosts were showing off a claw of similar size. Photo by Shannon K. Green.

Second, Armstrong is very concerned with what most reports would consider too mundane to document, such as food. If you’re out in the cold and the snow, what you ate will certainly be important. And, if a large concern is feeding and caring for the dogs in your team, then that will stick with you. Armstrong talks in specifics about the kind of food they had, which rations they would request versus what most others ended up eating (his team often had steak whereas the others usually had ‘K’ rations which consisted mostly of hard biscuits). The search, rescue and salvage teams had to work hard and went to difficult and pretty inaccessible areas to find the crash sites (I know, I’ve been to some of them), and it is nice to read about their exploits.

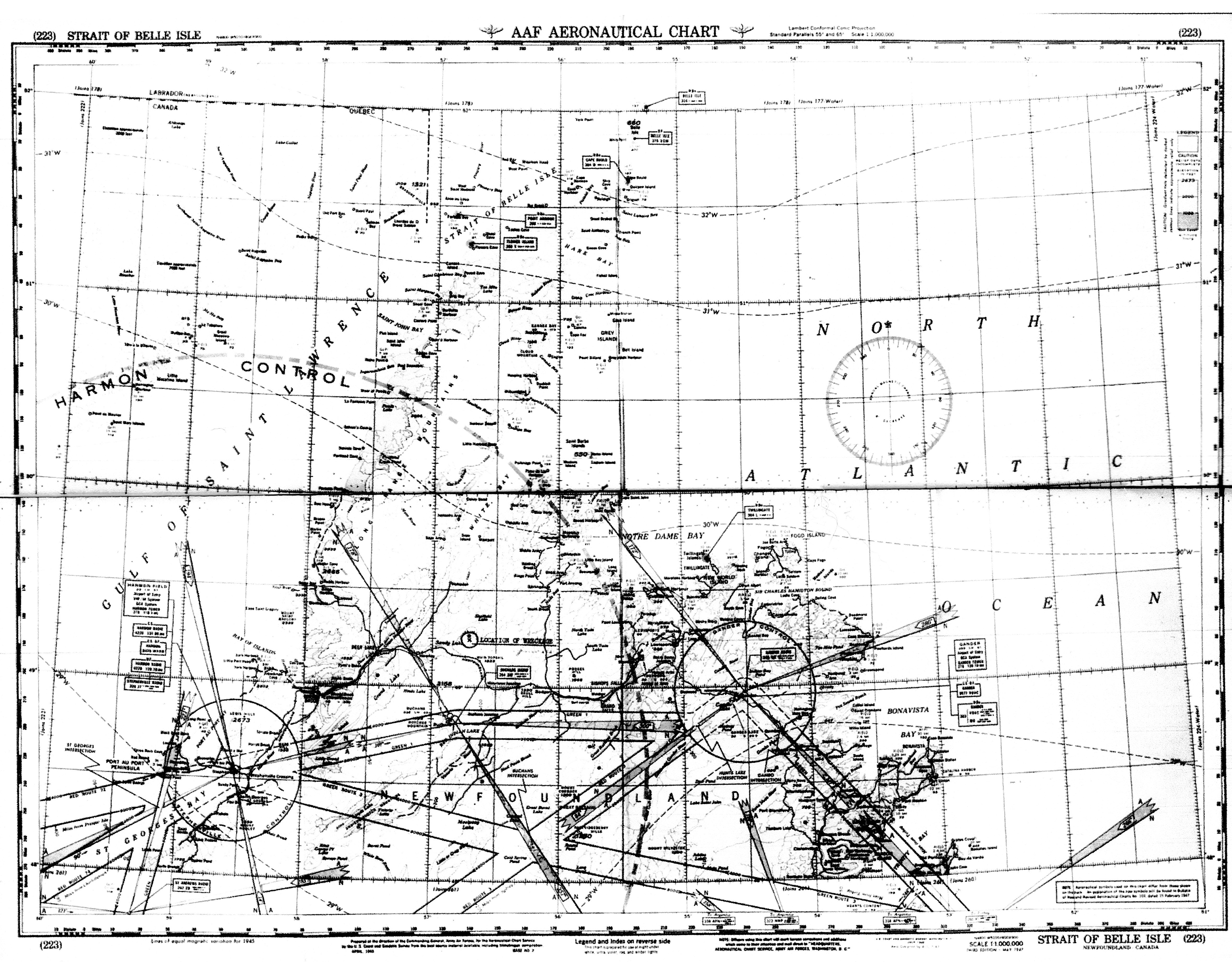

Finally, Armstrong was in Search and Rescue, so a big part of his job was to go to these crash sites. He served at Harmon Field in Stephenville (which he calls Stevensville) and went to a couple of crash sites in the area, ones I hope to visit some day and hopefully survey. His account will help recreate the story of the site. He also talks about how he searched the area around Hare Hill, with the goal of climbing the mountain to locate a crashed B-24. The B-24 was not located on that trip, and was not found until 1997 fifty miles north of Hare Hill, but the account was interesting because Hare Hill was renamed Crash Hill after the 1946 AOA crash which is of interest this summer. Some of the locations he talks about on his trip are familiar as I passed by them last summer.

What remains of the logging camp Armstrong stopped at on his way to Hare Hill. Photo taken in 2012 by Shannon K. Green

Armstrong mentions a small pond next to a smaller pond. Possibly it could be Alder Pond, seen here, with Crash Hill (Hare Hill) seen in the background. There is another small pond at the base of Crash Hill. Photo by author.

Armstrong was transferred to Gander and worked on a number of sites of interest. He mentions two of the three crashes that are on the other side of Gander lake from the town. He says it is a B-17 and a B-24 crashed on the hill, but it is actually two B-24s, both of which and a Canso in the same area, are of interest to archaeologists. Most interesting, is a long account of working on the Dolan site, including the trip out to the site and much of the recovery work done. Armstrong talks about making a camp and using a turret ring as a campfire ring. Although this site has been extensively surveyed by archaeologists, there was no evidence of a burnt turret ring, but another look at the site and a search specifically for that would indicate where the recovery camp was located. His story also agrees with what archaeologists found, such as the pilot and co-pilot chairs about 60 feet from the initial impact point. After all of the sterile military documents, it is wonderful to see the human element involved in WWII recovery efforts, especially the small anecdotes, such as how the crew were given a bottle of whiskey and another of rum, but the rum was accidentally dropped in the fire pit, and with a blue flash and shattered bottle, was completely consumed in seconds.

Armstrong served at Harmon Field and Gander Airport. Crash Hill and the Dolan site are marked as well. Map from MapSource 2010.

Overall, this book was a quick but very interesting read. I enjoy reading about the people who served and worked in Gander, it is a nice change from the technical reports and really brings the history of Newfoundland to life. I very much appreciate that Mr. Dolan sent me a copy of Armstrong’s book; I did not know the extent that sled dogs were used in search and rescue in Newfoundland and it gave an interesting look into Stephenville and Gander life during the war.

![Image 6 from the crash report. "Photo attachments #6 and #7 [missing] are general view of the wreckage". Griffing et al. 1947.](https://planecrashgirl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/SCN_0006-3-1024x944.jpg)

![Image 2 from the crash report. "Photo attachment #2 shows the spruce tree encircled [unclear on image], which helped determine the angle at which the aircraft struck the ground." Griffing et al. 1947.](https://planecrashgirl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/SCN_0008-2-1024x757.jpg)

![Image 5 from the crash report. "Photo attachment #4 [sic] is general view of wreckage taken from a point near left wing tip and showing area of most intense heat." Griffing et al. 1947.](https://planecrashgirl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/SCN_0006-2-1024x800.jpg)