Rear Admiral Sir Mark Edward Frederic Kerr was a proper sort of British gentleman, the son of an admiral, and who moved in royal circles. Apparently, he was also a bad poet. Kerr was an admiral at the start of the First World War, and received his pilot chit on 14 July 1914, testing after a total of 82 minutes in the air. He was the first flag officer of the Royal Navy to learn to fly.

Flying by Kerr

Quoted in Rowe 1977

Quietly stealing across the blue sky,

Out-pacing the Eagle the Air-craft will fly;

Caring for nothing in Heaven and Earth,

For this is a new life come into birth.

Kerr’s team arrived later than most of the entries, and decided to attempt their flight out of Harbour Grace, whereas the other entries were out of Trepassey, St. John’s, and what is now part of Mount Pearl.

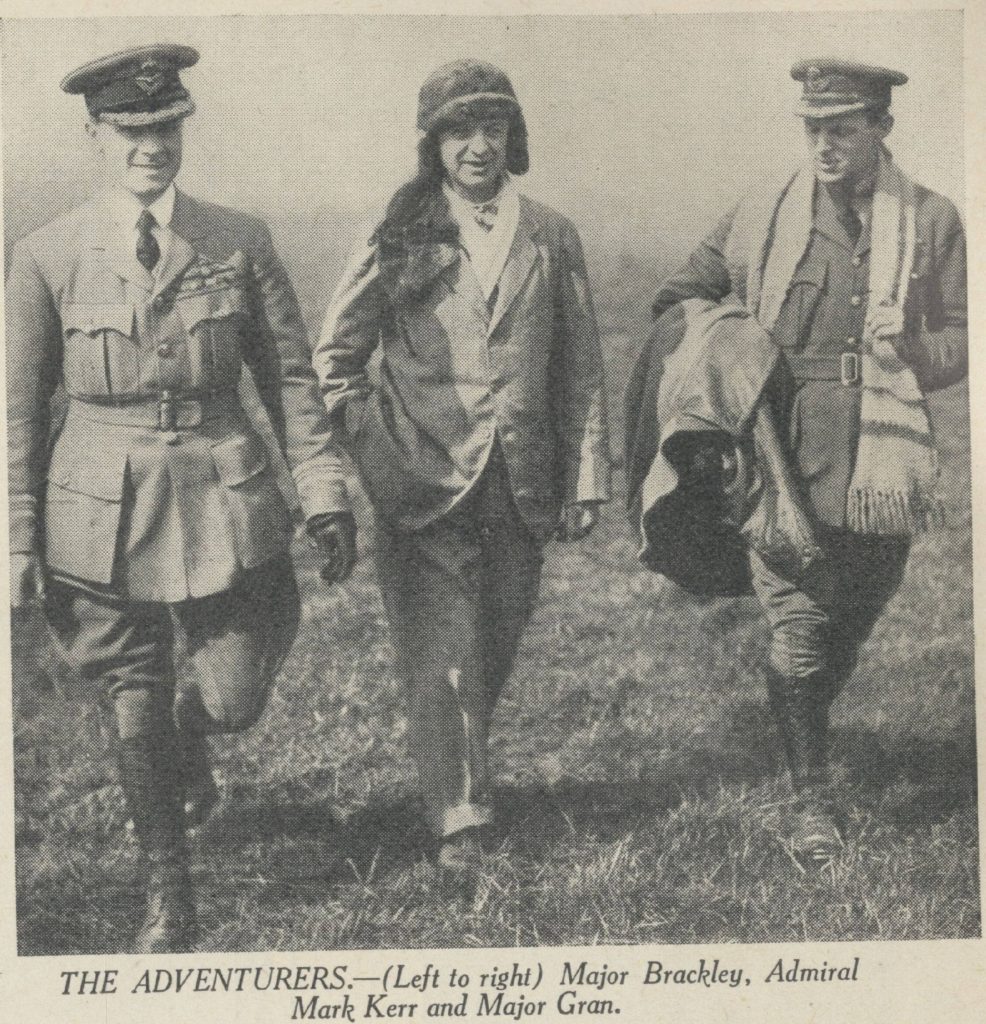

His team consisted of Major Herbert George “Brackles” Brackley as navigator, Major Jens Tryggve Harman Gran, a Norwegian born RAF pilot and member of Scott’s expedition to the South Pole, Mr R. Wyatt, Wireless Operator, Lieutenant Colonel E.W. Steadman, Assembly Engineer, Major G.T. Taylor, Meteorological Officer, and twelve mechanics. The team mostly consisted of men of high military and social ranking and as such, were the favourites of the elite in England to win the Atlantic Air Race and the Daily Mail prize.

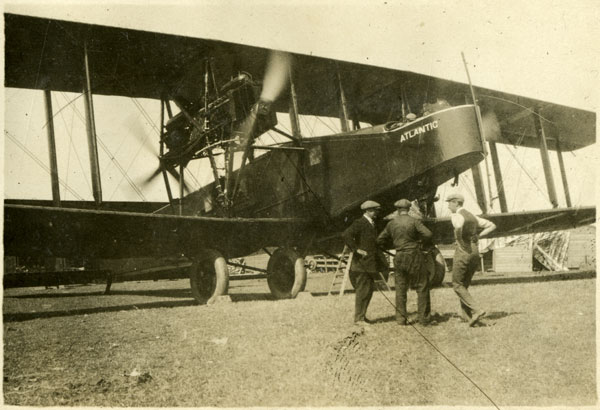

Kerr’s team would be flying the largest biplane in the world. He had a four-engine Handley-Page U-1500 Belin bomber called Atlantic. The aircraft arrived in 105 crates, some described as “large enough to be used as houses” (Parsons and Bowman 1983). The crates arrived on the RMS Digby to St. John’s, and were sent by rail to Harbour Grace. The crew ate and drank at the Crosbie Hotel (whereas the other aviators were at the Cochrane) before moving on to Harbour Grace. The crew boarded in people’s homes in the town. The crates were large enough that it was difficult to transport them, but that was solved by using the wheels from the aircraft to wheel the crates along the field. Once assembled, the aircraft weighted 14 tons and had to be pulled by a steam tractor.

Harbour Grace had to airfield at the time, and a runway was cleared at the east end of town, between the railway track and the harbour, parallel to Water Street, near St. Francis School. To build the 900 yards long and 100 yards wide runway, several small farms and gardens separated by rock pile fences and even houses, had to be dismantled. Some of the land had been in the families for years, but folks seemed willing to sell their land for the runway. The created field became known as “Handley Page on the Sea”.

It wasn’t one field, but a series of gardens and farms, with rock walls between them. These all had to be considerable obstructions, a barracks, which had to be destroyed. Gangs of men carried out this work and then, when all was cleared, a heavy roller, drown by three horses and weighed down with several hundred pounds of iron bars, eliminated the hummocks. The result, after a month, was a bumpy aerodrome

Joseph R. Smallwood, quoted in Rowe 1977

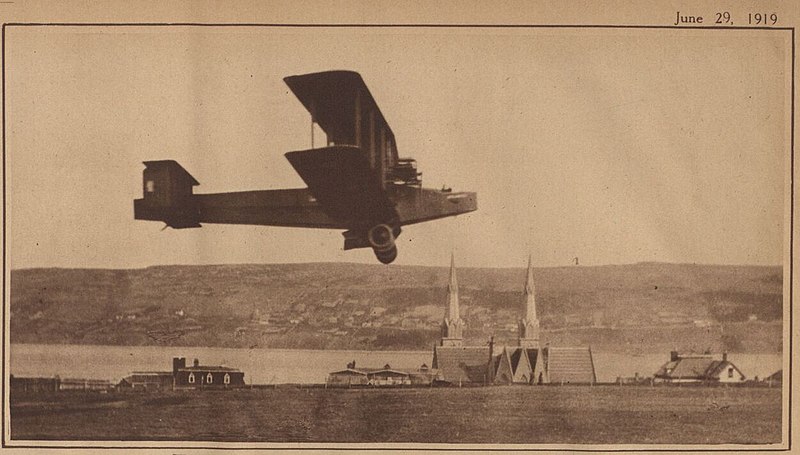

On a test flight, the aircraft left Harbour Grace in early June, and took 23 minutes to reach St. John’s, flew over, and returned to Harbour Grace. The test showed that there were issues with the engine’s cooling system that needed to be fixed. The flight did add some urgency to Alcock and Brown and the Vicker’s Vimy team to make the attempt. The urgency was unnecessary as Kerr had to order new parts from England, and the first that arrived did not fit.

This wasn’t Kerr’s only time in St. John’s (besides his arrival). He had a Rolls Royce leant to him by the Reid family, and would make the occasional trip from Harbour Grace to St. John’s where he would interact with the other aviators.

Before Kerr could attempt the transatlantic flight, Alcock and Brown made the successful flight across the Atlantic, winning the Daily Mail prize. Kerr wanted to attempt the Atlantic, but was ordered to quit the transatlantic attempt, but to instead tour the aircraft in the United States. Kerr attempted to arrange his visit to New York with the arrival of the R-34 on its east to west flight. The Reids were there to see the plane off (Brackley misspells them as Reeds). During the flight, Kerr exchanged wireless messages with the R-34.

The team left Harbour Grace for New York on 4 July 1919. On the way to New York, the engine started to overhead. There was a loud crack, the engine stopped, and as piece of metal went through the fuselage., which forced them down. In Parrshoro, Nova Scotia, they landed heavily on a small racetrack and destroyed the fuselage and damaged the tail. It took until October to repair the damage and continue to journey to New York. The aircraft was damaged again when it landed in Cleveland while en route to Chicago, and it was decided that the tour should be canceled and the aircraft was dismantled and shipped back to England. Parsons and Bowman (1983) speculate that there might have been a serious malfunction or defect which was a major factor in the cancellation of the tour.

Sources:

Brackley, H.E.

1938 Newfoundland to New York, 1919. The Aeroplane, p. 533.

Parsons, B. and B. Bowman

1983 The Challenge of the Atlantic: A Photo-Illustrated History of Early Aviation in Harbour Grace, Newfoundland. Robinson-Blackmore Book Publishers: Newfoundland.

Rowe, P.

1977 The Great Atlantic Air Race. McClelland and Stewart Ltd.: Toronto.

Will, G.

2008 The Big Hop: The North Atlantic Air Race. Boulder Publications: PCSP.

There is a fantastic collection of photographs available at the Rooms of the Handley Page called the Kerr-Brackley Photograph Collection