RCAF Lodestar 557 (DfAp-15)

By Lisa M. Daly

Adapted from Daly 2015, post first published on the Gander Airport Historical Society page.

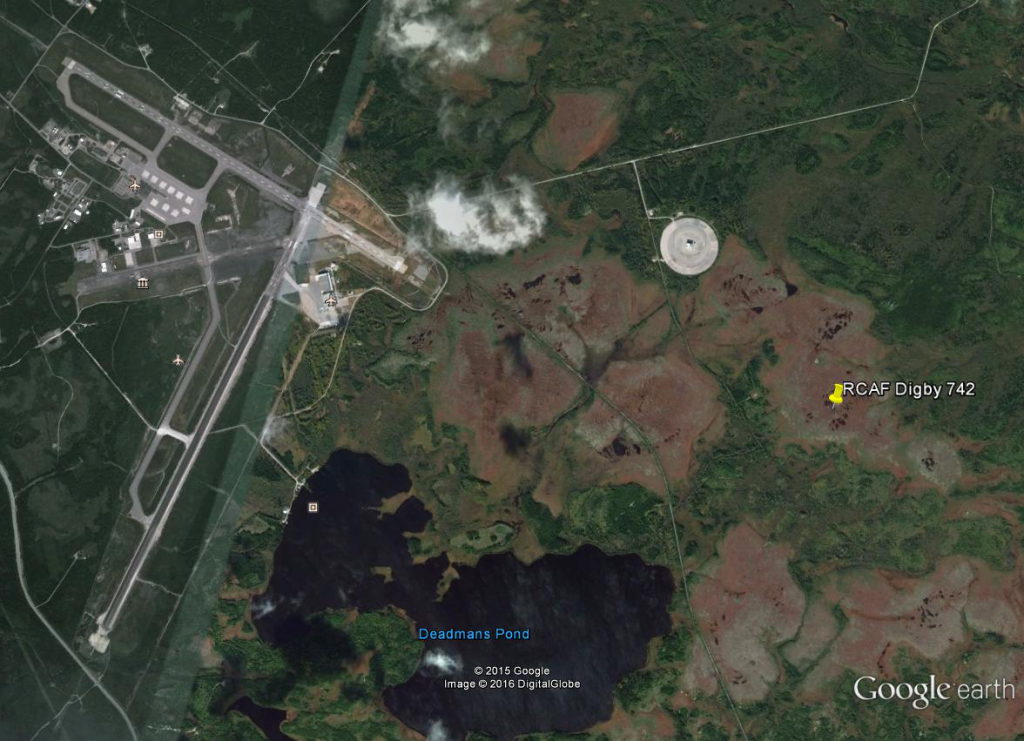

Map 1: Location of RCAF Lodestar 557 (DfAp-15) in relation to the Gander International Airport and side roads. From MapSource

Royal Canadian Air Force Lodestar 557 (Borden DfAp-15) is currently located on the edge of a tree-lined bog with all of the wreckage being located in the bog. It sits between Radio Range Road and Boot Pond Road (map 1), but is a long and sometimes difficult hike through trees and bog. In fact, researchers had difficulty finding the sites, even with the information provided by historians, locals, and aviation engineers. The site is relatively intact, but is heavily contaminated. The point of impact where the aircraft burned is heavily contaminated with fuel, and much of the water around the wreckage has the rainbow colour that shows contamination (figure 1). Any archaeological work done on site was done with protective material, including heavy duty gloves, to ensure that contaminated water did not touch skin. The site should be approached with caution and care taken to avoid any fuel contamination.

Figure 1: Contamination of the site. Photo by author, 2011.

Lodestar 557 departed Moncton. New Brunswick, at 2345 GMT on 7 May 1943 on a cargo transport flight to Gander. At 0313 GMT the following day, the aircraft contacted the Aerodrome Control Officer at Gander Station to request landing clearance. The aircraft was given landing clearance by P/O Thomas Howard Murray, aerodrome control officer, and was told to check their wheels down. The messages were acknowledged by 557. At this time the ceiling was practically unlimited. The aircraft was heard to pass over Gander airfield shortly thereafter, but the ceiling had unexpectedly fallen to 700 feet. This lowering of the ceiling possibly meant that ice may have formed on the aerials. It is unlikely that icing would have occurred on the wings or engines. This fly over was apparently done on instruments. The Lodestar contacted the Control Officer to indicate they had missed the field and were to try again. The aircraft then acknowledged being given the ceiling height and barometric pressure by the station.

|

Name |

Rank | Unit | Duty | Injuries |

| Svendsen, H. | WO2 | #164 Sqn. | Pilot | Fatal |

| Allen, C.H. | WO2 | #164 Sqn. | 2nd Pilot | Fatal |

| Sewell, A.G. | LAC | #164 Sqn. | W/Opr. | Fatal |

Table 1: Crew of RCAF Lodestar 557. From Mulvihill 1943.

At this point, the landing of the aircraft on the control tower side was taken over by the station manager of Trans Canada Airlines (TCA), Mr. Harry Beardsell. The aircraft was carrying cargo and under the operational control of TCA and therefore should be under TVA radio coverage. Instructions were passed to the aircraft by TCA as to the proper landing procedures for Gander, and these were acknowledged. The aircraft broke through the now 600 ft. ceiling, and was advised to circle and approach runway 27 (note, runway 27 is no longer in use at YQX; ourairports.com). At this point, TCA spoke directly to the pilot. According to Beardsell, he advised Svendsen to make one more attempt before proceeding to Sydney where the ceiling was at 1000 ft. and visibility was 3 miles. P/O Murray, who was listening to the communications between the control tower and Lodestar 557 denied that the aircraft was advised of a secondary landing location. According to the radio log, it was actually Lodestar 557 who suggested that it would try for one more landing and if not successful would return to Sydney and TCA seconded the decision. The aircraft approached, but seemed to be lined up with the wrong runway and was advised to circle again and attempt runway 27. P/O Murray believed that the boundary lights were confusing 557, causing it to line up with the wrong runway, so he switched off the lights and informed the aircraft through Beardsell. One the second attempt, the aircraft did not turn enough and was again told that it would probably not make it to the runway and to attempt again. The aircraft was told to make a right turn over the field near the airport, but it could be seen that the aircraft would not make the turn successfully. The pilot was advised to pull up two or three times by TCA, but at this point 557 was in a steep bank and went into a stall, losing altitude until it crashed. One witness saw the aircraft moments before the crash and stated it was flying very low at 200 ft. with engines functioning properly. The crash was indicated by a flash followed by a second, brighter flash, indicating it had crashed and was burning. Fire trucks and ambulances were dispatched to the scene. It crashed at 0340 GMT on 8 May 1943 approximately two miles east of the RCAF Station in Gander. All crew were killed and found in their proper seats in the aircraft (Table 1; Mulvihill 1943). The crew were buried at the Commonwealth War Graves in Gander.

According to the accident report:

AIRCRAFT: Scattered over a small area but distributed over approximately 190 yard line. The starboard wing tip made first contact with a tree and then the port with the resultant that the starboard wing came off first, followed by the port. The fuselage continued on and finally both wheels struck the ground, at this point the aircraft must have bounced into the woods where it caught fire and was almost completely burned out except for portion just forward of the rear door to and including the empennage.

EMPENNAGE: The empennage [tail assembly] was twisted completely around and was facing in the opposite to normal direction (figure 2).

Figure 2: The tail of the aircraft, slightly twisted and fragmented. Photo by author, 2011.

WINGS: Starboard damaged but not seriously while the port was fairly well intact, but both were torn from centre section outboard of root fittings.

FLAPS: It was observed on examining the crash that the section of flaps remaining on the centre section was in the up position. It is improbable the flaps would have been retracted as a result of the crash.

INSTRUMENTS: There were no instruments or controls present to indicate the attitude [sic] of the aircraft or the performance of the engines.

ENGINES: Port engine was seriously damaged while the starboard was completely burned out. The salvage from the two engines would be almost negligible (figure 3).

Figure 3: Engine in the main area of the crash. Photo by author, 2011.

UNDERCARRIAGE: The undercarriage was severely twisted but it appears certain that it was locked “down” at the moment of impact, since one of the [botusting] cylinders was found in the retractor or “undercarriage locked down” position and it is considered impossible for the cylinder to be forced into this position by a crash. The other cylinder was partially extended but this could have been caused by the crash. In addition one of the drag struts was observed to be buckled as indicating it had experienced a severe compression load which it could not experience if the undercarriage had been retracted.

GENERAL: Other than the above, all other parts of the aircraft were so badly damaged or burnt that they were of no value in disclosing further information (figure 4; Mulvihill 1943b).

Figure 4: The crash site. Photo by author, 2011.

The aircraft had been certified as airworthy and in serviceable condition; the pilot, WO2 Svendsen, was fully qualified to fly a Lodestar in all conditions, and had twice flown the same route to Gander on transportation flights. The cause of the crash was determined to be “pilot error, while attempting to get into position to make approach under low ceiling” (Mulvihill 1943). The aircraft slipped or stalled after changing from a left turn to a right turn in an attempt to realign with the runway. Because it was already in low altitude, the slip or stall caused it to strike the trees while trying to recover from the turn. The report recommends safety changes to the airbase. As Lodestar 557 had to make a final attempt because it had aligned with the wrong runway, the report determined that the runway lighting system of the RCAF station in Gander was confusing and should be studied and improved (Mulvihill 1943).

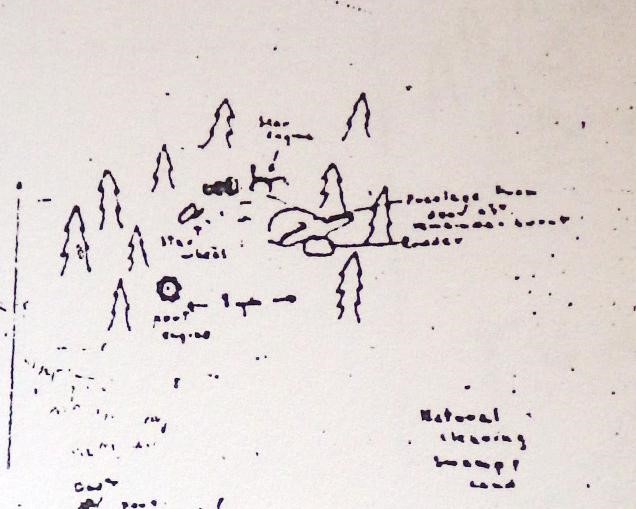

Figure 5: Sketch of the RCAF Lodestar crash site. From Mulvihill 1943.

Based on a comparison of the archaeological investigation and the incident report, the site is mainly intact. Even a comparison of the sketch in the report, the site map, and recent pictures of the site show an almost identical layout of the crash site. It is known that this site has been visited (based on conversations with people from Gander), but very little seems to have been removed. Interestingly, most people who visited the site in the past, or who know of it, have the impression that the site has largely been recovered or looted by salvagers in the recent past. Contrary to this, the site shows very little disturbance, to the extent that the tail rudder appears to be in the same location as indicated by the 1943 map. In agreement with the crash report, the cockpit, including all instruments, was destroyed. What is present on the site is an area of slag with pieces of instruments and aircraft scattered throughout. This area was explored by archaeologists, but instead of trying to measure in every piece and burnt fragment, some of which could not be identified because they were too deep under contaminated water to be moved, it was decided that the points of measurement would be taken around the area and large, identifiable pieces, such as engines, would be measured separately. In fact, it was a similar method used to create the 1943 map (figure 5; figures 6 & 7).

Figure 6 7: The burnt area of the crash site. Photos by author, 2011.

Due to the fact that the crash report describes the scene in such great detail, and the site is still very much intact, the archaeological analysis does not add much information about the crash. One exception is that pieces of the aircraft were found up to and over 30m west of the main impact point. These pieces were measure into the map first by using a 30m measuring tape until pieces were too far, then they were measured directly from the stadia rod. Most of the site was measured into the map using a measuring tape and surveyor’s level (figure 8). The pieces the furthest from the wreckage indicated that the burnt area was not the first area of contact during the crash, but that Lodestar 557 clipped the trees and began taking damage prior to the final impact. This is mentioned in the report, but the artifact distribution better indicates how the aircraft came in while attempting to turn.

Figure 8: Surveying the wreckage. Photo by Kathleen Elwood, 2011.

While it was stated that the archaeological investigation did not add much to the information available in the incident report, this site is of archaeological importance due to the fact that it is very much intact. It is a relatively well-known crash site around Gander, but because it is a fair distance from any road or path, it is difficult to access and is therefore mostly untouched by site visitors. As well, the fact that the crash report and the archaeological investigation line up so neatly is a way for archaeologists to check their methods and make improvements for the investigation of other sites as necessary. Very little post-war damage has occurred at this site, and now that it is listed as an archaeological site and given its remote location, it will continue to remain intact.

Sources:

Daly, L.

2015 Aviation Archaeology of World War II Gander: An Examination of Military and Civilian Life at the Newfoundland Airport. Doctoral (PhD) thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Hillier, D. (historian)

2010 Personal Communication

Mahr, R. (aviation engineer)

2010 Personal Communication

Mulvihill, J.C.

1943 Lodestar Aircraft: R.C.A.F. No. 557: Accident to Above at Gander Nfld., on 7-5-43 WO. 2. H. Svendsen, WO. 2 A.C. Needham LAC A.G. Sevell All Killed. Royal Canadian Air Force, Gander.

Ourairports.com.

2006 YQX pilot info. http://ourairports.com/airports/CYQX/pilot-info.html#runways (Accessed 23 Feb 2016).