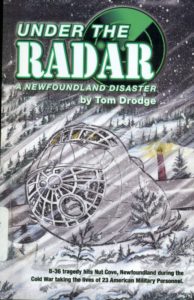

I’m not thrilled to be posting two book reviews in a row, but I took this one and Under The Radar by Tom Drodge out of the library at the same time, and I thought it best to do the review before I have to return them. Hopefully I will have something more exciting for next week.

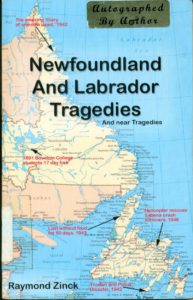

Newfoundland And Labrador Tragedies: And near Tragedies by Raymond Zink is a self-published work that looks at five exciting events in Newfoundland and Labrador. Of course the aircraft incidents caught my eye. The events are around two students from Bowdoin College who end up taking 17 days to get from what is now Churchill Falls down the Grand (then Hamilton, now Churchill) River to safety in 1891, the Truxtun and Pullux disaster of 1942, the 1942 Saglak Bay crash, Ranger Hogan’s 50 day survival after bailing out of a Ventura in 1943, and the 1946 Sabena crash near Gander.

This is an incredibly interesting book for anyone not familiar with these events. There are stories of extremes of human survival, even if in some cases the people did not survive. Those in the Saglek Bay crash survived for at least 55 days in the middle of winter (10 December 1942 to the last diary entry on 3 February 1943) before starving. Even when they were found, it was noted that they did not freeze to death, which shows an impressive level of survival skill.

I did not know about the Bowdoin College students who were send up the Grand River to document the falls, nor that there is a canyon named after them. I certainly did not know about their ordeal trying to get back down the river. Four students started the journey, but two turned back after one injured his hand. The other two made it to the falls, but lost much of their supplies due to a fire and had to walk back down the river to the meeting point. For most of the walk they survived off squirrels that they shot. For this reason, I found this entry to be the most interesting.

Sabena wreckage. From ganderourtown.nl.ca.

The reason why I did not find the other events as interesting is that the author does not really bring anything new to the stories. I was familiar with them, and have read the Saglek Bay “Diary of one now dead”, read not only Frank Tibbo’s Charlie Baker George about the Sabena, but also the reports that are found in the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador. Similarly, I have read about Ranger Hogan’s experience both in the archives and in books about the Newfoundland Rangers. The Truxtun and Pollux disaster has been in the news relatively recently with the death of Lanier Phillips and his story gaining interest in the United States.

Wreck of the USS Truxton. From originalshipster.com.

Zinck’s style mainly consists of copying newspaper, diaries and reports verbatim to let the reader see the story. In some cases he does add information, but typically it is commentary such as the fact that the two trappers, Bruce Shea and Abbott Pelley, who were instrumental in helping survivors in the first night after the crash, were not recognized for many years for their involvement. He also makes commentary on the fact that those who crashed in Saglek Bay did not take advantage of the fact that they had gun and could have hunted (the diary entries talk about fox and seals nearby) and relied only on the food they had on board the aircraft. That is valid commentary, but I don’t understand why, when talking about Ranger Hogan and Corporal Butt, Zinck starts to talk about the fat content of porcupines and how they are great as survival food, then states that there were neither porcupines nor squirrels in Newfoundland at the time. Hogan and Butt were in the woods for 50 days with no provisions and survived off of 12 rabbits and whatever berries, leaves and greens Hogan could find. I did learn about the Hogan Trail, and have been wanting to get back to the Northern Peninsula, and will be sure to walk this commemorative trail when I do.

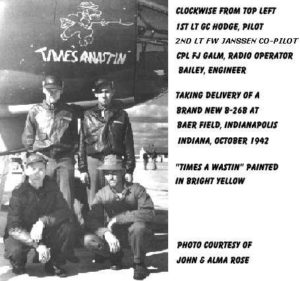

Crew of the B-36 Times A’Wastin’ which crashed in Saglek Bay. From A Crash In the Wilderness

And, as usual, there are the editing problems that often accompany self-publication. In some cases, Zink is inconsistent in the spelling of places. The book is littered with typos and formatting issues, and like the porcupine comments, there are odd tangents which do not add to the telling of the events.

If you haven’t heard about some of these events in Newfoundland and Labrador history, then this is a great book to pick up. But if you are familiar with them, then give it a pass.

Zinck, R.G.

2009 Newfoundland And Labrador Tragedies: And near Tragedies. Publish Yourself: Halifax.

At the Burgoyne’s Cove crash site. Photo by Lisa M. Daly.

At the Burgoyne’s Cove crash site. Photo by Lisa M. Daly.