Captain Charles W. Fairfax “Fax” Morgan of the Royal Navy was the first to arrive on the Digby. A veteran British aviator, he claimed to be the descendant of the buccaneer, Sir Henry Morgan. Most of his family had nautical ties, but he was the first to also take to the air. During the First World War he earned the Distinguished Service Order and the Croix de Guerre for taking down German aircraft. He did take a bullet injury to the leg, leaving him without one leg.

On the boat ride to Newfoundland, he contracted influenza and was hospitalized. There he had conversations with up and coming journalist Joseph Smallwood, who covered the air race extensively for The Evening Telegram.

Morgan told Smallwood about how he would need flat land for a runway, and Smallwood arranged for the land alongside Quidi Vidi Lake. When feeling well enough, Morgan went traipsing through the snow to inspect the field and found it suitable. enough, although far from perfect He returned to England. As Morgan was the first one to come to Newfoundland to try for find an airfield, it did start a fair bit of speculation in the city about what the air race would mean to Newfoundland.

On April 11, 1919, he returned with navigator Frederick “Freddie” Raynham and their Martinsyde biplane named through the combination of the first syllable of each of their last names, the Raymor. Hawker and Grieve were, at this point, in Newfoundland and had just conducted their first flight, with Quidi Vidi claimed, had found their airfield at Glendenning Farm.

Raynham earned his pilot’s license in 1911 at 17, and was issued the 85th aviator’s certificate in Britain. He was inspired when he saw the plane Louis Bleriot used to fly the English Channel. He was the youngest of the aviators in the transatlantic competition, was an accomplished pilot, and might have been the first aviator to get out of a spin alive. He flew Avro planes, then Martinsyde monoplanes in aerial derbies and worked by testing aircraft and giving flight lessons. Often though, he was a common participant in derbies, he often came second to Harry Hawker.

In the lead up to their attempt, Morgan did make public jabs at Hawker and Grieve for their life-saving equipment. Morgan was reported to have said “I’m afraid those lifesaving gadgets are of little use. For myself, I have decided that I may as well take one deep breath if we strike the sea. We will be a very small speck in a big ocean out there.”

Morgan was actually one of the most popular of all of the aviators in the race. He would talk to everyone, from poor children to the St. John’s elite. He would joke about his cork leg and would play practical jokes on anyone, but would be a good sport when they would backfire. Morgan would take questions, but also make up lies about the aircraft to tell kids. To tell what sort of characters they were, amongst their crates were some labeled “Aircraft Spares: Handle With Care” which actually held two dozen bottles each of brandy, gin, rum, whiskey, sherry, and port. In light of prohibition in Newfoundland, they decided to bring their own liquid encouragement.

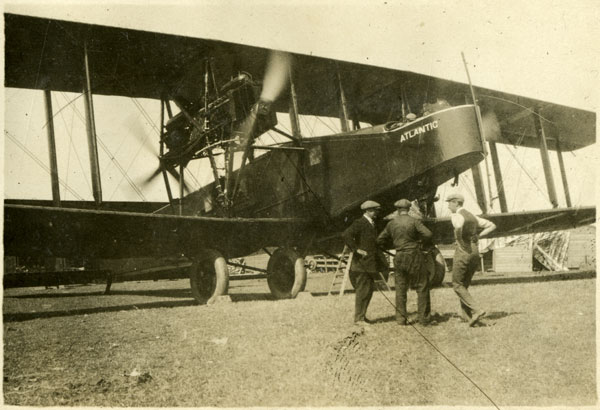

Seven days after the Raymor was uncrated, Morgan and Raynham were ready to test it. The aircraft was wheeled across the road to their airfield. Local reporters, as well as Hawker and Grieve, were present to see the test. They played up the showmanship of the test, wearing their Burberry flying suits, fleece-line boots, and leopard-shin hats. The test was successful and the aircraft took off at the thirty-seven yard mark.

The aviators had a gentlemen’s agreement to inform the others of their attempts, Hawker, Grieve, Morgan, and Rayhnam all ordred extra sandwiches from the Cochrane Hotel the Sunday after the Nancies had made it to the Azores. The day Hawker and Grieve made their attempt, they made a point of flying over Morgan and Raynham, who were also preparing to take off. Their aircraft had the speed potential to overtake Hawker and Grieve in the Atlantic, so the team rushed to takeoff. The Raymor was fater than the Atlantic, so could have potentially overtook Jawker and Grieve. Given that they were at Quidi Vidi Lake, Morgan and Raynham had a huge crowd of over two thousand had gathered. The aircraft was too heavy with a full load of fuel, 350 gallons of fuel, some food, and letters. Raynham decided that they were going to take off, even though the wind was somewhat behind the aircraft. Because it was now a race with Hawker and Grieve, it was an act of desperation. Just after 4pm that evening, the aircraft was started. With a full load, the aircraft didn’t start to lift off until after 300 yards down the runway. When it started to rise, it was due to hitting a bump, rose, wavered, and plummeted down so hard that the undercarriage buckled. It his a soft spot, and crashed nose first into the field. Raynham cut the engines and fuel supply to prevent fire.

The crowd came forward to help, but Raynham managed to pull himself out. Morgan had to be helped as his cork leg made it more difficult to get out, and he was more injured. Raynham had recieved a blow to the abdomen, was bruised, winded, and had a bleeding nose, which was taken care of on site. At the time of the impact, Morgan had been looking over the side of the plane and the left side of his face was hit. He needed to be supported as he walked away from the plane. He suffered from sock and was taken to the home of Gerald Harvey, where he fainted. He was examined, received stitches in his cheek and two over his eye. His left shoulder and leg were both badly bruised, and he was in great pain. He was blind in one eye, caused by the bruising. There had been a small piece of shrapnel received in the war in that eye, which was unknown to the doctors in Newfoundland. Morgan rested for a few days, and, during this time, he said he planned to return to England, but would return to St. John’s to set up a air service. Unfortunately, doctors prohibited him from every flying again. He left St. John’s, but on his way out, he wrote a letter to the Evening Telegram praising the place and the hospitality he received. He said “The doctors have run the death knell on my ever flying again, but the Raymor will fly again, and a better man than I am. You will be blessed by seeing her rise again. My heart and thoughts will always be with her.”

After Alcock and Brown made their successful flight, Raynham still wanted to attempt the crossing. He first approached Mackenzie-Grieve to be his navigator, but Grieve declined. Instead, he found Lieutenant Conrad Biddlecombe, a pilot and master mariner, to fly with him.

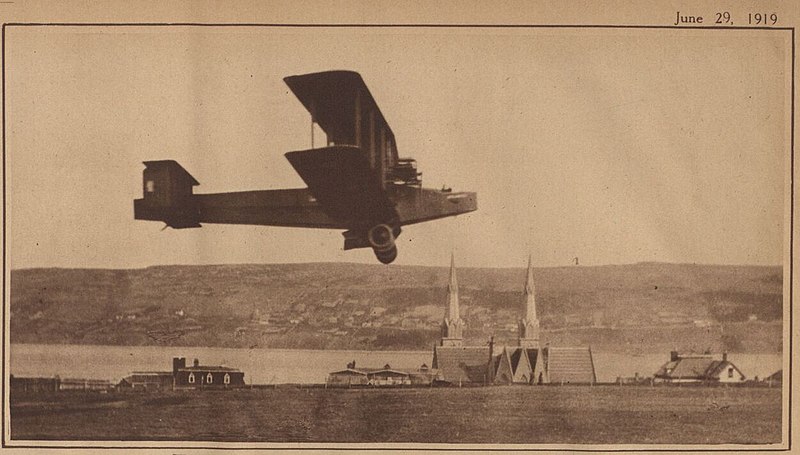

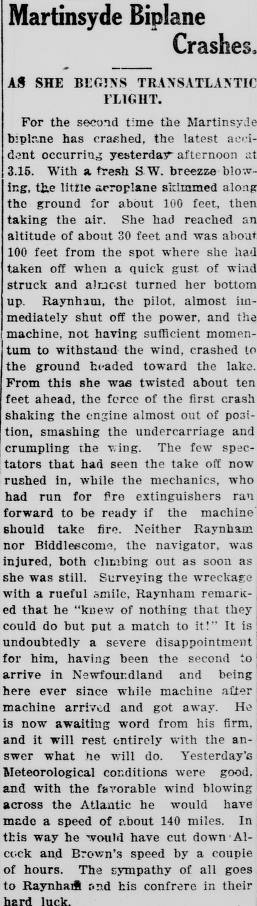

The Raymor‘s engine had to be replaced, and much of the aircraft had to be rebuilt. Much of this was done in a garage on the outskirts of St. John’s. The aircraft was renamed the Chimera, and on July 17th, they made another attempt. Hundreds of people came out to see this attempt. At 300 yards, the aircraft skipped into the air, shuddered, caught by a side gust of wind, which caused the wing to dip and touch the group. Raynham righted the aircraft, but it crashed down. The undercarriage, propeller, wing, and fuselage were all badly damaged. This time, neither were hurt, but gave up on the attempt and Raynham caught the first ship he could back to England. The pieces of the aircraft were later shipped back as well.

Raynham went back to working with Martinsyde, but in 1920, when the company was in trouble, he started to look for a new job. On 21 March 1920, he set a world speed record of 161.4 miles per hour over a kilometre course, but soon went back to finding himself in second place in many competitions. He even played number two to the main actor in a movie called “The Hawk”. He formed the India Air Survey and Transport Company, working in India and Burma. He and his wide, Dodie Macpherson, moved to the United States, bought a motor home, and wandered for six years until he suffered a heart attack and died in 1954. He is buried in Colorado.

Sources:

Moon, E.

1959 Air Race From Newfoundland: The Story of the Alock and Whitten-Brown Flight Forty Years Ago. Atlantic Advocate, 49(11): 45-56.

Rowe, P.

1977 The Great Atlantic Air Race. McClelland and Stewart Ltd.: Toronto.

Will, G.

2008 The Big Hop: The North Atlantic Air Race. Boulder Publications: PCSP.