Some of the sites that I investigated as part of my thesis had very little remaining on site. This was seen with the Ferry Command Hudson FK690, and will be seen with future posts. Whenever a site is accessible, it is at risk to have objects removed, whether for collectors or to sell as scrap metal. In the case of Hudson FK690, the public were encouraged to remove pieces as the highway was supposed to pass over the crash site, but in other cases, it was accessibility which caused the destruction of a site, not permission.

USAAF B-17 42-97493 (DfAp-09) can be found in the Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest in Gander, Newfoundland. This is an educational facility that demonstrates the history of forestry in Newfoundland and forestry practices. It consists of a series of beautiful trails and interpretation panels (map 1). The Demonstration Forest includes a wonderful picnic area which overlooks Gander Lake, and a longer trail which goes from Thomas Howe to the Silent Witness site. I have enjoyed the trails within the Demonstration Forest, but have not yet enjoyed the longer trails or the snowshoe trail.

Map 1: Trail Map for the Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest showing the location of the B-17. From www.GanderCanada.com

Along the P.G. Tipping Trail there sits one of the B-17s engines (figure 1 & 2). This is the largest element which remains of this aircraft, and it is in full view for anyone walking the trail. The wreckage does continue off trail, and down into the trees. To complete this survey, I had to get permission to go off-trail. This survey was done a little more carefully than most because it had to be done with as little impact to the site as possible. In other situations, it was permissible to uncover wreckage, turn pieces over, and to remove branches that were within the line of site of the surveyor’s level (figure 3). This means that some measurements are estimated, and extra care was taken to leave as little evidence of the work as possible (a datum peg was left on site for any future archaeologist who wishes to build on this work). In exchange, the Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest was given a copy of the crash report (available from AAIR), an inventory of what was found on site, and my own report. This they could use to monitor the site and to use in the training of new staff.

Figure 1: The engine visible from the Tipping Trail. Photo by Lisa M. Daly, 2010.

Figure 2: Photo of one of the engines taken at the time of the investigation. Bollis et al. 1944.

Figure 3: Some wreckage was obscured by the forest. Photo by Lisa M. Daly, 2010.

On 29 December 1943 at 2303 GMT, USAAF 42-97493, took off from runway 27 into the wind in “a normal manner” (Bollis et al.1944). The aircraft was departing Gander for Valley, Wales. According to the crash report, the aircraft climbed steeply – so steeply that one witness, F/O Fisher, remarked that the climb was similar to that of a single engine bomber rather than a B-17 – to about 500 to 600 feet then banked to the left to turn to the south. At approximately 15 degrees into the turn, the nose of the aircraft dropped suddenly. Cpl. George W. Stiffler witnessed the crash from the Gander Control Tower, and stated that the engines did not appear to be having trouble, with the exception that three engines were exhausting blue flame and the #1 engine was exhausting yellow flame. The aircraft was still in a turn when it crashed. Witnesses and investigators agree that the left wing touched first, the aircraft caught fire immediately, skidded several hundred feet, and then exploded with flames shooting 500 to 600 feet into the air. All crew and passengers were killed (table 1; Bollis et al. 1944).

| Name | Rank | Serial No. | Duty | Injuries |

| Ryan, Bruce E. | 1st Lt. | O-795488 | Pilot | Fatal |

| Wooten, Stephen A. | 2nd Lt. | O-519302 | Pilot | Fatal |

| Gentile, John J. | 2nd Lt. | O-798698 | Navigator | Fatal |

| Thayer, Charles (MMI) | Sgt. | 37212166 | Engineer | Fatal |

| Norton, Frederick A. | Cpl. | 12092803 | Radio Operator | Fatal |

| McCain, Ballard D. | 2nd Lt. | O-803839 | Pilot | Fatal |

| Lineham, Paul J. | 2nd Lt. | O-811689 | Navigator | Fatal |

| Killela, Thomas R. | S/Sgt. | 32455257 | Engineer | Fatal |

| Nightower, Howard W. | Sgt. | 14140152 | Radio Operator | Fatal |

| Boucher, Daniel L. | Sgt. | 39555248 | Gunner | Fatal |

Table 1: USAAF 42-97493 B-17 crew and passenger list. Adapted from Bollis 1944.

At the time of the crash, RCAF B-24J 593 was making its initial approach to Gander and witnessed the incident. The Liberator circled the crash and gave the control tower the position of the crash before landing (figure 4). The accident investigation team arrived at the scene at 1230 GMT, on 30 December 1943. The path of the aircraft was observed, as well as several parts of the aircraft (figure 5). The investigation concluded that, as observed by witnesses, the aircraft did strike the ground while on a 15 degree bank to the left. The left wing was torn completely off and was about 50 feet to the left of the fuselage. The right stabilizer was found about 100 feet from where the aircraft first impacted the trees, and the fuselage was broken into several pieces (figure 6). The nose and the pilot’s compartment was demolished and burned. The tail broke off, and all four engines and propellers were demolished or severely damaged. The damage to the engines, propellers, and cockpit was severe enough that neither engine could indicate power output, or lack thereof, nor could the instrument readings at the time of the crash be determined. Therefore, the investigator, Major Richard Loomis, could not determine the cause of the crash (Bollis et al. 1944).

Figure 4: View of where the aircraft damaged the trees as it crashed. Bollis et al, 1944.

Figure 5: Pictures of the wreckage taken at the time of the investigation. Bollis et al 1944.

Figure 6: Possible image of the wing or fuselage taken at the time of the investigation. Bollis et al. 1944.

The aircraft was checked prior to takeoff, with all checks being deemed “O.K.” Issues of an oil leak and problems with the carburetor heat gauges were reported, but were signed off on. Minor maintenance was done to the radio equipment, with a new fish put on antenna band A. Mechanical problems were not blamed for the accident. Overall, the cause of the accident was never determined (Bollis 1944).

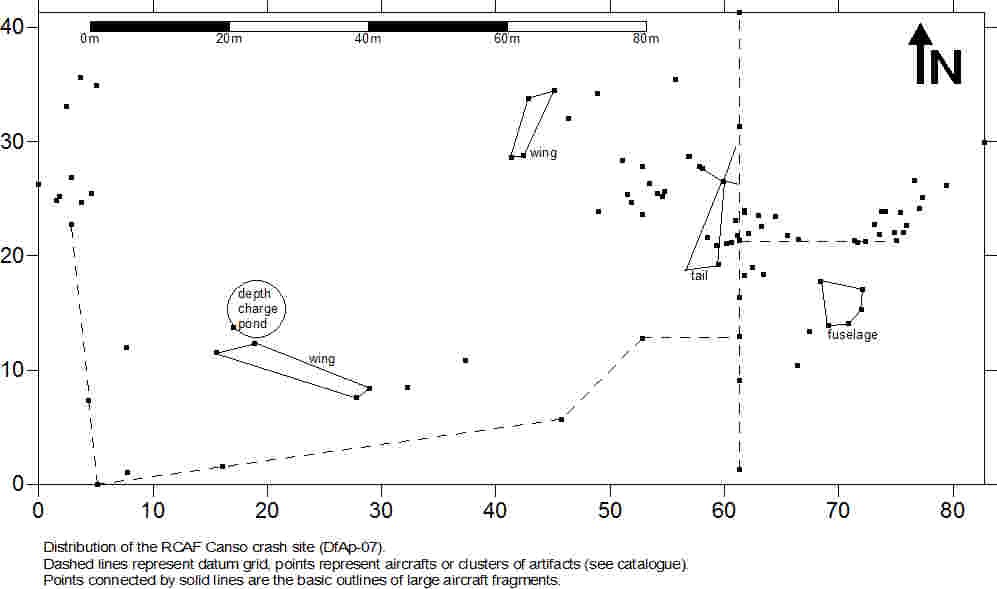

Map 2: Site distribution with the trail as reference. Created on Surfer 8.

The crash report indicates that the debris was spread over a large are, but, as can be seen by the site map (map 2), there is very little that remains. The majority of what was found was in a relatively clear area, and nothing was found deeper into the trees (figure 7). It should be noted, that most of what was found was not useable for scrap material, and even though only one engine was found, others, especially if they broke apart during the crash, may have been removed either during the investigation or later. Images from the time of the crash show much more material that was once on site. Talking to staff members, they would notice things moving around the Forest. For instance, one staff member found an oxygen tank learning against a pole in an area cleared for the power lines. Yes, oxygen tanks, when punctured, can travel huge distances, but for this one to be found in an area cleared after the crash and to be highly visible would indicate that it had been placed there recently. The staff member decided it would be best to remove the tank and store it at the interpretation centre (figure 8).

Figure 7: Looking at what remains of the aircraft on the site. Photo by Lisa M. Daly, 2010.

Figure 8: Oxygen tank recovered by Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest Staff. Photo by Lisa M. Daly, 2010.

One of the goals of this particular project was to help with the preservation of this site. As seen, the site has been heavily scavenged over the years, and while staff cannot continuously monitor the crash site, they can use the archaeological inventory and map to have an idea of what was on the site in 2010 and if things are being removed or moved around the site. This can help them better manager the site and know if anything further needs to be done to protect the site.

As of now, the crash site is not just a memorial to those who died in the crash. It is also used as a teaching tool. When it comes down to it, it is the Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest, and it demonstrates the life and management of a forest. The crash site is used to teach visitors and school groups about how catastrophic incidents, such as a plane crash, can impact a forest by noting how 70 years later the area is different, but also how it has recovered.

Photo by Lisa M. Daly, 2010.

Sources

Bollis, W.L.J., R. Loomis and W.D. Ward

1944 “Accident No.44-12-29-582,” U.S. Army Air Forces Report on Accident. War Department Report.

Interpretation panel in the Thomas Howe Demonstration Forest giving information about the crash. Photo by Lisa M. Daly, 2010.