Going to start this post with a plug for the event I’ve been helping to plan. Normally I don’t do such things, but I feel as this is, at its core, a blog about history and archaeology, then this is fitting. On March 25 there will be a heritage forum brought to you by Heritage Tomorrow NL (formerly Youth Heritage NL). For anyone between the ages of 18 and 35 and who is interested in heritage, history, archaeology, folklore, museums, etc., this is an event for you. We will be having a heritage skills competition, then really focusing on networking and talking to other like-minded young people, getting to know each other, and hopefully creating networks so that we can help each out. Registration is $10 and includes lunch from Volcano Bakery. Click here for details.

I’ve been jumping around the province a bit, and am heading to Stephenville for this post war incident. No archaeology here as the aircraft crashed on the runway and survived the accident. The main reason for sharing this one is actually the great pictures that were featured in the report at The Rooms. I really wanted to share those with my readers as so many of my pictures from the era are often grainy and copied so many times it’s hard to really see what’s happening.

On 13 August 1948, The Evening Telegram printed a small article about an incident at Harmon Field. The article reads:

Three Escape Death In Aircraft Crash At Harmon Field

Three crew members of a twin-engined Lockheed Hudson narrowly escaped death at Harmon Field this week when their aircraft, while coming in to land, veered from the runway as the pilot lost control, groundlooped and crashed.

The plane was being ferried from Dorval airport in Montreal to South Africa, and was owned by the Hanley Aviation Company of Johannesburg, South Africa. The plane called at Harmon en route.

Parts of the plane will be salvaged by the owners at a later date. The crew of the wrecked aircraft left Harmon Wednesday night for Montreal.

The aircraft in question was a Hudson Mark III, serial number 6386 (also sometimes listed as AC #41-23569), with the South African registration of ZS-DAF and it crashed. The crew consisted of Edward R. MacLeod, pilot from the United States, John P. MacMahon, navigator from the United States, and JohnH. Hluboky, radio officer, also from the United States. None were injured in the crash which took place at 23:53 GMT on 9 August 1948.

The aircraft involved had a long history prior to the accident. It was manufactured by the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation and was delivered to the Royal Air Force Ferry Command under the service number BW-707. After 20 hours flying time with the RAFFC, it was transferred to the Royal Canadian Air Force on 12 February 1942 and retained until 26 August 1946. It then went into storage. At this point, it had a total flying time of 1729 hours and 30 minutes. During its service in the RCAF, the Hudson was used in Canada for flight training and as part of a Search and Rescue Squadron (it was here that it was fitted with an airborne lifeboat). It was removed from storage on 20 May 1948 and flown from Greenwood, Nova Scotia, to Montreal, Quebec. On 16 July 1948, the aircraft was purchased by Simple Aircraft Limited from the Canadian War Assets Corporation, then sold again to Hanlys Aviation (Pty) Limited of Johannesburg, Union of South Africa. Long-range tanks were added to the aircraft, but no documents suggest when that happened. It is assumed it was done in preparation for the flight to South Africa. The pilot said the work was done by Ross Aero at Montreal Airport, but no details could be found for the incident report. The engines were ones put on during the RCAF service, and both were certified as fit for the ferry flight to South Africa.

From McGrath 1948

Prior to the ferry flight, inspections were made determining that the aircraft was fit for the flight, but the ferry permit limited flying to daytime flying. Otherwise, it was certified to make the flight to Johannesburg via Gander. MacLeod, the pilot, was an experienced ferry pilot and claimed to have 2,500 hours, 300 of those at night. In the war, he served with United States Air Transport Command and made 12 ocean crossings. Since the war he operated a flight school and charter service using small aircraft, mostly Lockheed aircraft. Prior to this flight, he did not fly the Hudson, but did inspect it prior to the flight. He stated that it was not until after he was in flight that he noted that the aircraft would not cruise at 170 knots, but the report points this out as a discrepancy. Had he been as familiar with Hudsons as he claimed, then he should know they cruise at 160-180 miles per hour, not 170-190 knots and the pilot believed. MacLeod also did not carry an Aircraft or Route Information Manual, did not know the empty weight or gross weight of the aircraft and carried to information or instrument landing procedures for any of the airports on his route.

The aircraft left Montreal at 1922 GMT 9 August 1948, and, as the accident report states, “even on a very optimistic flight plan could not have reached Gander before sunset” (McGrath 1948). The Hudson arrived over Harmon Field in Stephenville at dusk and requested permission to land at Harmon. Due to the daylight restrictions on the permit, the pilot thought it best to not continue to Gander and have to land in the dark. The request was passed on to the Civil Aviation Division in Gander and permission was granted on the understanding that the aircraft would proceed to Gander the following day and that the need to land at Stephenville would then be investigated. As the aircraft approached, MacLeod noted that the undercarriage indicator light did not come on when he lowered the undercarriage. He asked the Control Tower if the undercarriage was down, and due to the low light, the Tower could not see it and asked that the aircraft fly over at low altitude. With that passing, the Tower confirmed that the undercarriage was indeed down, and so the aircraft came in for a power-off landing.

From McGrath 1948

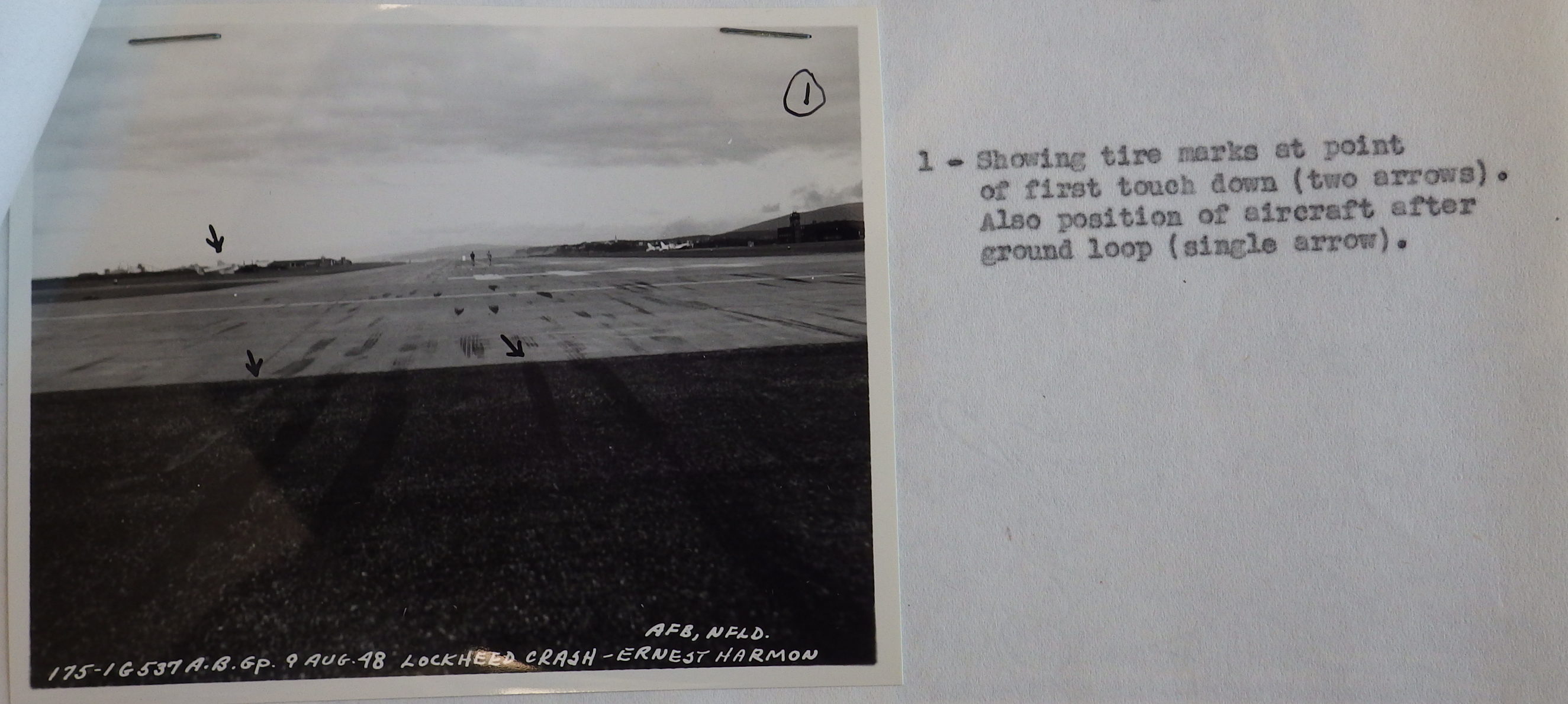

Witness statements from United States Air Force personnel stated that the aircraft made a very low approach, so low that they were not sure that the aircraft would even make it to the runway and thought it would land along the approach lights. At this point, the engines were heard and the pilot opened the throttles so that the aircraft regained some altitude. The aircraft touched down hard on the tarmac about 15 feet short of the end of the runway, bounced 30 to 50 feet into the air and touched down again about 300 feet from the first point of contact. The aircraft then began to swing to the left and the aircraft ran off the left side of the runway ab out 100 feet from that first point of touchdown. At this point the left wheel hit and smashed one of the runway lights, but the wheel was not damaged. The undercarriage collapsed ad the aircraft pivoted on the left wheel making a turn of 270° to the left finally coming to a rest about 100 feet from the edge of the runway. There was no fire and the crew were uninjured. The left engine was still idling when the crash crew arrived. The pilot could not explain the swing and stated “that after the bounce the aircraft ‘stayed on’ with the tail down and the rudders became ineffective” (McGrath 1948). The report states that this was normal for Hudson aircraft in a tail down attitude. MacLeod said he tried to correct the swing by using the right brake, but it had no effect and he was afraid to often the left engine in case it cause the aircraft to swing to the right. The report states that there were no marks on the runway to indicate that either brake had locked.

As previously stated, the aircraft had been refitted with long distance fuel tanks. During the investigation, it was determined that neither the empty or gross weight of the aircraft was known. The all-up weight would have been 15,400 lbs. and it was rated as such by inspectors prior to the flight, but at departure from Dorval, with full tanks, the aircraft would have weighed considerable more than that. Due to the lack of data, it was impossible for investigators to say if weight was a factor.

From McGrath 1948

In the accident the aircraft:

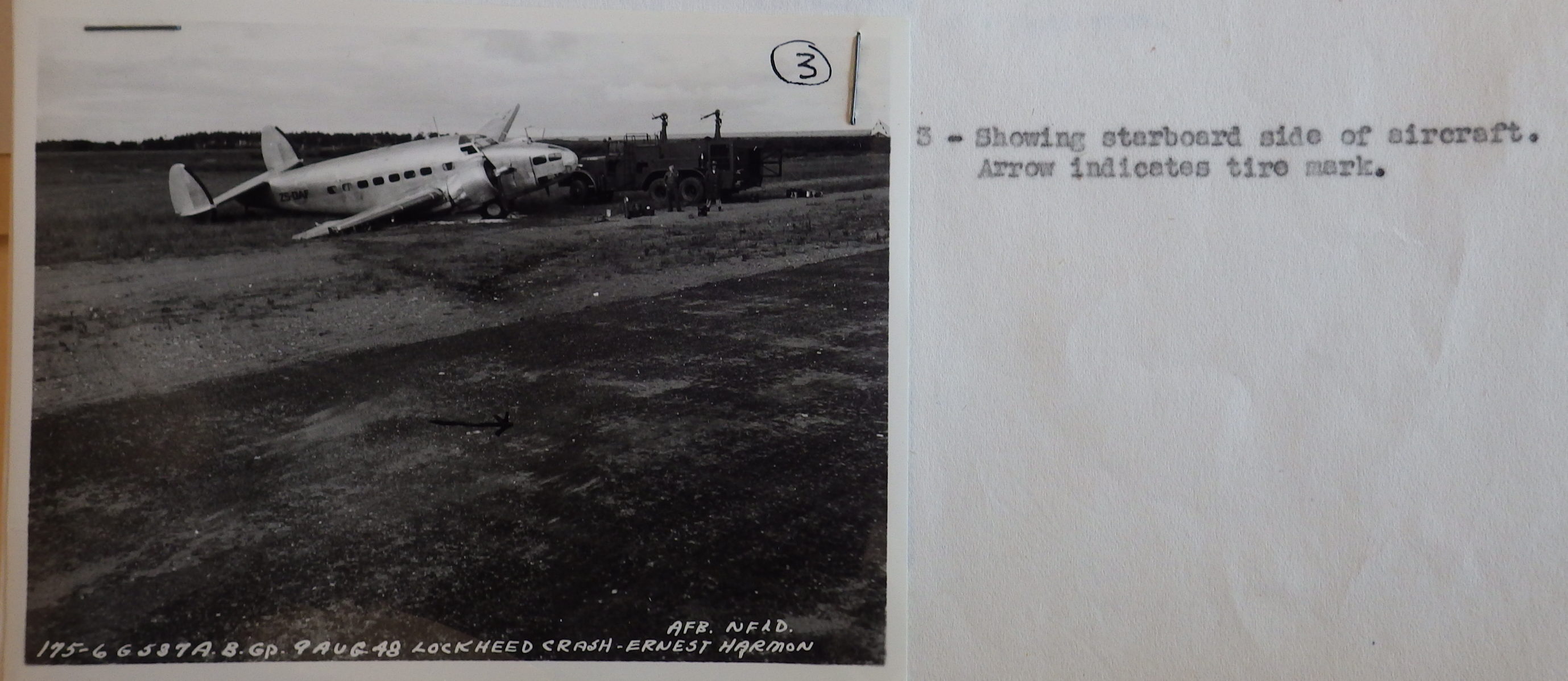

sustained major damage on the starboard side; the port side was undamaged. The starboard wing was twisted lengthwise and the starboard engine mount was badly twisted; the starboard undercarriage had collapsed in a forward direction; the starboard wing root was damaged; the starboard flap was badly crumpled; the bottom of the starboard tail fin was bent inwards; the starboard cirscrow was bent and had cut through the starboard side of the nose of the aircraft (McGrath 1948).

It was also noted at this time that the plexiglass nose had been broken at some point prior to the accident and had a piece of fabric stuck over the break to close the hole. There was also an opening in the bottom of the aircraft which was made for the attachment of the airborne life boat for RCAF SAR missions. This opening had not been covered before the aircraft left Montreal. The investigation also showed that the brakes will had holding power, but the drag link on the starboard undercarriage had an old crack in the upper end of the drag link rod near the attachment point to the actuating strut. This link rod appeared to have failed when the aircraft slid backward at the end of the ground loop.

From McGrath 1948

In the opinion of the investigators, the accident “was a result of failure by the pilot to correct a swing developed by the aircraft following a bad landing” and “tail heaviness of the aircraft may have been a contributary cause”. (McGrath 1948)

There were a number of irregularities found that were brought to the attention of the governments of Canada, Newfoundland, South Africa and United States so they could investigate any breaches in their respective air regulations. Such issues included the fact that the aircraft was granted South African registration before ownership had been acquired by Hanlys Aviation (Pty) Limited, and the South African validation was issued before the Canadian Ferry Permit which it validated. The pilot had no South African documentation authorizing him as a US airman, and the aircraft radio was not licensed. There was no record of work being done to the aircraft after it was removed from storage, even thought long range tanks were installed, and the weight and balance were unknown. There was no copy of the Department of Transport Information Circular T/5/47 on the aircraft as required by law, and the pilot had no Route Information Manual nor information on instrument approach procedures for the airports on his route. The pilot also used fuel from the cabin tanks first, causing the rear tanks to be heavier, especially when coupled with the fact that there was 300 lbs. of freight in the tail. Finally, nationality and registration markings were not painted on the wings. They were painted on the fuselage only (and the previous marking were still visible).

From McGrath 1948

The reports were sent off to the governments and a copy sent to Hanly’s Aviation Office in New York. The report was not completed or sent until October due to the delays in attempting to get the weight information. Finally, the copy that was sent to Wainwright Abbot, the American Consul General had an added note from J.S. Neill, the Commissioner for Public Utilities and Supply, which thanked the US authorities at Harmon Field for their assistance to McGrath in his investigation (Neill 1948).

Sources:

McGrath, T.M.

1948 Civil Aviation Division Newfoundland Aircraft Accident Investigation Report Number 10. On file PANL Accident to Hudson Aircraft AG/57/14

Neill, J.S.

1948 Letter to the American Consul General, 12th October, 1948. On file PANL Accident to Hudson Aircraft AG/57/14

Unknown

1948 “Three Escape Death In Aircraft Crash At Harmon Field”, The Evening Telegram. 13 August 1948, p. 5.